the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Quantifying erosion in a pre-Alpine catchment at high resolution with concentrations of cosmogenic 10Be, 26Al, and 14C

David Mair

Naki Akçar

Marcus Christl

Negar Haghipour

Christof Vockenhuber

Philip Gautschi

Brian McArdell

Fritz Schlunegger

Quantifying erosion across spatial and temporal scales is essential for assessing different controlling mechanisms and their contribution to long-term sediment production. However, the episodic supply of material through landsliding complicates quantifying the impact of the individual erosional mechanisms at the catchment scale. To address this, we combine the results of geomorphic mapping with measurements of cosmogenic 10Be, 26Al, and 14C concentrations in detrital quartz. The sediments were collected in a dense network of nested sub-catchments within the 12 km2-large Gürbe basin that is situated at the northern margin of the Central European Alps of Switzerland. The goal is to quantify the denudation rates, disentangle the contributions of the different erosional mechanisms (landsliding versus overland flow erosion) to the sedimentary budget of the study basin, and to trace the sedimentary material from source to sink. In the Gürbe basin, spatial erosion patterns derived from 10Be and 26Al concentrations indicate two distinct zones: the headwater zone with moderately steep hillslopes dominated by overland flow erosion, with high nuclide concentrations and low denudation rates (∼ 0.1 mm yr−1), and the steeper lower zone shaped by deep-seated landslides. Here lower concentrations correspond to higher denudation rates (up to 0.3 mm yr−1). In addition, 26Al 10Be ratios in the upper zone align with the surface production ratio of these isotopes (6.75), which is consistent with sediment production through overland flow erosion. In the lower zone, higher 26Al 10Be ratios of up to 8.8 point towards sediment contribution from greater depths, which characterises the landslide signal. The presence of a knickzone in the river channel at the border between the two zones points to the occurrence of a headward migrating erosional front and supports the interpretation that the basin is undergoing a long-term transient response to post-glacial topographic changes. In this context, erosion rates inferred from 10Be and 26Al isotopes are consistent, suggesting a near-steady, possibly self-organised sediment production regime over the past several thousand years. In such a regime, individual and stochastically operating landslides result in the generation of an aggregated signal that is recorded as a higher average denudation rate by the cosmogenic isotopes. Although in-situ 14C measurements were also conducted, the resulting concentrations are difficult to interpret as soil mixing (due to landsliding), sediment storage or an increase in erosion rates might influence the 14C concentration pattern in a yet non-predictable way.

- Article

(8751 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(391 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

In alpine environments stochastic processes such as landslides often drive sediment production and condition the occurrence of debris flows (Kober et al., 2012; Clapuyt et al., 2019). During periods of strong hillslope-channel coupling, the processes operating on the hillslopes deliver detrital material to the channel network, where sediment from various sources becomes mixed and transported downstream. As a consequence, the sediments at the outlet of such a catchment are a mixture of detrital material generated through a large variety of erosional mechanisms in different locations in the upstream basin. This makes it challenging to allocate the detrital material and to quantify how the different sub-catchments and erosional processes have contributed to the overall sediment budget (Battista et al., 2020). This is particularly the case for those basins that are underlain by bedrock with a homogenous lithology, which prevents the identification of different sediment sources using petrologic fingerprinting methods (e.g., Stutenbecker et al., 2018). In such a context, in-situ 10Be has proven a useful tool to quantify the generation of sediment through erosion (Bierman and Steig, 1996; von Blanckenburg, 2005) across a large range of catchment sizes – from small headwater basins (∼ 1 km2; Granger et al., 1996) to major river systems such as the Ganges and Amazon rivers (Wittmann et al., 2009; Dingle et al., 2018). In addition, 10Be-derived denudation rates have also been successfully applied to explore the controls of various parameters on surface erosion such as: topography and rock strength (DiBiase et al., 2010; Carr et al., 2023), environmental conditions (Reber et al., 2017; Starke et al., 2020), rock uplift as well as climatic variables including precipitation (Chittenden et al., 2014; Roda-Boluda et al., 2019), runoff and runoff variability (Savi et al., 2015), and frost cracking processes (Delunel et al., 2010; Savi et al., 2015). However, a successful 10Be-based assessment of basin-averaged denudation rates requires that the material at the sampling site is well mixed (Binnie et al., 2006), representing the contributions from the various tributary basins according to the rates at which sediment has been generated in them. In catchments where sediment has been episodically supplied e.g., by landslides, denudation rate estimates may be biased towards the impact of a specific sediment source (Bierman and Steig, 1996; Savi et al., 2014; Brardinoni et al., 2020), particularly if samples are collected in small basins (Yanites et al., 2009; Marc et al., 2019). Accordingly, erosion rate estimates for basins where the sediment production has largely been controlled by landslides requires a sampling strategy where the corresponding upstream size of the basin increases with landslide area if the goal is to capture a stable long-term erosion rate signal (Niemi et al., 2005; West et al., 2014). This is also the main reason why few studies have targeted small catchments with stochastic sediment delivery (Niemi et al., 2005; Kober et al., 2012). Nonetheless, recent work (DiBiase, 2018) has demonstrated that landslides primarily introduce some scatter, but not a strong bias into erosion rate estimates. Furthermore, the use of paired cosmogenic isotopes with different half-lives, such as 10Be–26Al (Wittmann and von Blanckenburg, 2009; Wittmann et al., 2011; Hippe et al., 2012) or 10Be–14C (Kober et al., 2012; Hippe et al., 2019; Skov et al., 2019; Slosson et al., 2022) have enabled to reconstruct the occurrence of sediment storage in the source-to-sink sedimentary cascade. They also improved our understanding about the importance of transient erosional effects on the generation of the cosmogenic signals in fluvial material (e.g., Hippe et al., 2012).

Here, we use information offered by concentrations of cosmogenic 10Be, 26Al, and 14C in riverine quartz, which we combine with the results of geomorphic mapping. The goal is to (i) trace the origin of the sediments, (ii) document the influence of landsliding on the long-term sediment fluxes, and to (iii) explore the scale-dependency – in space and time – of the resulting cosmogenic signals. In contrast to most previous studies, we particularly target small basins to identify the impact of landslides on the generation of cosmogenic signals. To this end, we focus our work on the Gürbe basin situated at the northern margin of the European Alps. Erosion in this basin has been largely controlled by a large variety of erosional processes including sediment supply through deep-seated landslides (do Prado et al., 2024), thus making this basin an ideal target for our goals. We thus address our aims using the concentrations of the three cosmogenic isotopes (10Be, 26Al, and 14C) in quartz minerals, which we extracted from detrital sediments in the channel network of the Gürbe basin.

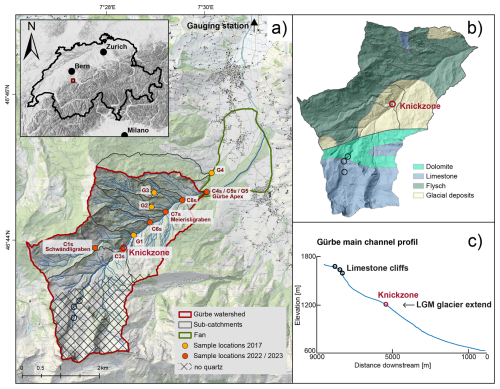

The study area, the 12 km2-large Gürbe catchment, is situated at the northern margin of the Swiss Alps (Fig. 1a). The Gürbe River, with a ∼ 8 km-long main channel, originates at an elevation of approximately 1800 m a.s.l. There the landscape is characterised by steep cliffs made up of Mesozoic limestones that are part of the Penninic Klippen belt (Jäckle, 2013) (Fig. 1b). These units are partially covered by a several meter-thick layer of glacial deposits (i.e. till, Swisstopo, 2024a). The orientation of the corresponding moraine ridges suggest deposition by small, local glaciers during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) ca. 20 000 years ago (Bini et al., 2009; Ivy-Ochs et al., 2022). The headwater area of the Gürbe catchment hosts a second main tributary, the Schwändligraben River (Fig. 1a). It originates within Cretaceous to Eocene Gurnigel-Flysch units, which are alternations of marls, sandstones, polymictic conglomerates and mudstones (Winkler, 1984). The landscape in the source area of this tributary is characterised by a swampy terrain and ancient deep-seated gravitational slope failures. At approximately 1200 m a.s.l., a knickzone that corresponds to the highest glacial deposits of the LGM Aare-glacier in this region (Bini et al., 2009) separates the landscape into an upper and a lower zone. At this knickzone, the longitudinal profile of the Gürbe River steepens from originally 6.5° upstream of this knickzone to 9.3° farther downstream (Fig. 1c). Similarly to the region upstream of the knickzone, the bedrock in the lower part of the Gürbe basin is predominantly composed of alternated sandstone and mudstone beds that either occur in the Gurnigel-Flysch unit (Swisstopo, 2024a) or in the Lower Marine Molasse (Diem, 1986). In this lower part of the Gürbe basin, the hillslopes are between 20 and 25° steep and covered by a dense forest made up of spruce.

Figure 1Overview of the Gürbe watershed. (a) Study site showing the locations where cosmogenic samples were taken during the two sampling periods in 2017 (Latif, 2019) and 2022/2023. The figure also illustrates the corresponding sub-catchments. The no-quartz area, which is due to the predominant occurrence of limestone lithologies, was excluded from the calculations of the denudation rates and the morphometric properties; (b) simplified lithological map, and (c) longitudinal profile of the Gürbe main channel. Note that the occurrence of knickpoints is indicated by circles. The knickzone, situated at ca. 1200 m a.s.l., corresponds to the height of the LGM glacier in this region (red circle). It marks the transition from the upper to the lower part of the catchment. Further knickzones in the upper part (black circles) are conditioned by differences in the lithologic architecture of the bedrock. The digital elevation model (DEM) is taken from the Federal Office of Topography swisstopo (Swisstopo, 2024d), and the overview map showing the relief is available from Swisstopo (Bundesamt für Landestopografie swisstopo et al., 2023).

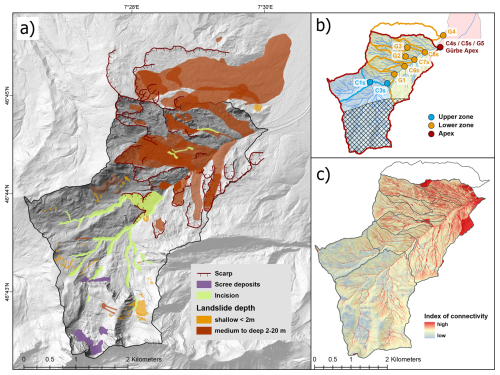

Several areas prone for the occurrence of deep-seated landslides have been identified in the lower part of the Gürbe basin (Zimmermann et al., 2016). Most of them have been inactive for several tens of years (Zimmermann et al., 2016). During these times, sediment has mainly been generated through a combination of overland flow erosion and incision by small torrents that are perched on these landslides. Yet, all of these landslides have also been re-activated periodically, though not simultaneously. During such periods lasting several days up to several months, they have experienced high slip rates of several meters per day (Zimmermann et al., 2016). This has resulted in a major re-mobilization of mass also during the following years when the landslides have become inactive. Notably, most of the active landslides are not directly connected to the main Gürbe channel (Figs. 2, 3d, e). Therefore, the delivery of material from these landslides to the trunk stream occurred primarily via lateral tributaries. In cases where such deep-seated mass movements do reach the Gürbe River, undercutting by fluvial processes has triggered secondary shallow-seated landslides at their toes, resulting in material from the large landslides being directly supplied to the trunk stream. The combined effect of the aforementioned processes is a relatively high mean annual sediment discharge of ca. 900–2600 m3 a−1 at the downstream end of the Gürbe basin (Zimmermann et al., 2016; do Prado et al., 2024). This was the main reason why approximately 140 check dams have been built during the past century to stabilise the streambed, reduce the gradient, and thereby regulate the transport of bedload (Salvisberg, 2017; do Prado et al., 2024). At the downstream end of the lower section, the Gürbe channel transitions into the deposition zone, forming an approximately 4 km2 alluvial fan with a distinct apex situated at 800 m a.s.l. On this fan and farther downstream, the Gürbe River flows in an artificial channel that is stabilised by check dams and flood protection dikes. After passing through an artificial deposition area, the river enters the Gürbe valley floodplain, where the stream flows in a confined channel until merging with the Aare River approximately 20 km downstream.

Figure 2Geomorphic map of the Gürbe catchment. (a) Mapping indicates two distinct geomorphic zones: (1) the southern, upper part of the catchment is characterised by incised channels, limited scree deposits, and shallow landslides; (2) the northern, lower part is a dissected and topographically complex landscape marked by multiple medium- to deep-seated landslides. Note that the difference in red colors (medium- to deep-seated landslides) is due to a superimposition of two landslides. (b) Delineation of three zones: the upper zone (blue), the lower zone (orange), and the sampling locations at the fan apex (red), which represents the site where sediment is supplied to the depositional area. The area marked with crosses is considered not to supply quartz minerals (see Fig. 1). (c) Index of connectivity with respect to the fan apex. The upper zone exhibits a low connectivity between hillslopes and the channel network, while the connectivity increases markedly in the lower zone, reflecting that the pathway of sediment transfer – relative to the fan apex – is more direct for sediment originating in the lower part than in the headwater region. Digital elevation model (DEM) from the Federal Office of Topography swisstopo (Swisstopo, 2024d).

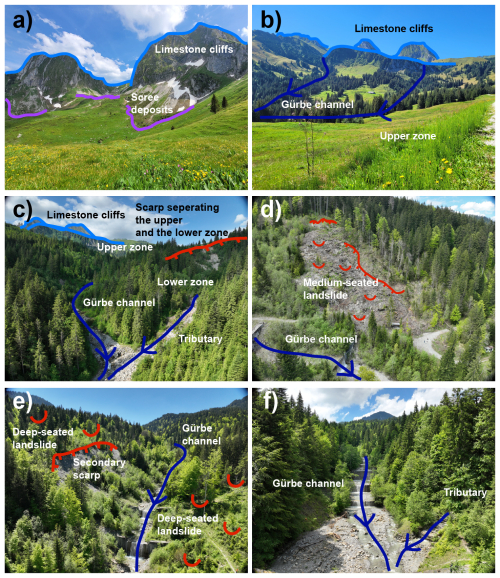

Figure 3Drone images visualizing the catchment's characteristics. (a) Upper zone with limestone cliffs and scree deposits. (b) Upper zone with smooth landscape and the limestone cliffs. (c) Knickzone area separating the upper from the lower zone. (d, e) Scars in the landscape along the Gürbe main channel indicating that landslides have recently been active. (f) Confluence between the Gürbe River and a tributary torrent upstream of the apex.

The runoff conditions of the Gürbe River are characteristic for a pre-alpine environment, exhibiting a nivo-pluvial discharge regime (Jäckle, 2013; Salvisberg, 2017). Between 1981 to 2010 the discharge of the Gürbe River has been continuously measured at the Burgistein gauging station that is situated ca. 5 km downstream of the Grübe fan (Fig. 1a). During this period, the mean annual precipitation rates have ranged from approximately 1100 mm yr−1 in the alluvial fan area to nearly 2000 mm yr−1 in the headwaters of the catchment (Frei et al., 2018; based on MeteoSwiss, 2014). Due to the low water storage capacity of the soils, including the soils in the Penninic Klippen belt and the regolith cover of the highly saturated, low-permeability Gurnigel Flysch and Lower Marine Molasse units, the catchment rapidly responds to high rainfall rates, resulting in peak floods with short durations (Ramirez et al., 2022). The gauging records indeed show that intense summer thunderstorms, with rainfall intensities up to 30 mm h−1, tend to generate runoff with large discharge magnitudes. Such an event with an extremely high discharge of 84 m3 s−1 occurred on 29 July 1990 (Ramirez et al., 2022; do Prado et al., 2024). In contrast, the mean annual discharge has been approximately 1.3 m3 s−1 during the survey period. These high discharge variabilities emphasise the torrential character of the Gürbe River (Ramirez et al., 2022; Salvisberg, 2022).

Following the scope of the paper, we integrated geomorphic and geologic data with cosmogenic nuclide-derived estimations of catchment-averaged denudation rates to yield a holistic picture on the origin of the sedimentary material and the source-to-sink sedimentary cascade of the clastic detritus. We used the swissAlti3D high-resolution digital elevation model (DEM; Swisstopo, 2024d) with a spatial resolution of 2 m as a basis, which we then re-sampled (with the nearest neighbour algorithm) to a 5 m-DEM for further scaling analysis. We justify this re-sampling to a lower resolution because a grid with a lower resolution prevents the introduction of artefacts upon calculating the flow paths (such as roads, and artificial scours). Additionally we corrected the DEM of the Meierisligraben catchment (Fig. 1) to account for the re-direction of the corresponding channel during the reactivation of the corresponding landslide in 2018, a feature already documented in the swisstopo map 1 : 10 000 (Swiss Map Raster 10; Swisstopo, 2024c). This correction was performed by digitizing a new DEM using the contour lines of the respective map as a basis. Next, we used the natural neighbour interpolation method (Sibson, 1981) as implemented in ArcGIS Pro v3.1 to create a raster dataset from the contour lines. The corrected area was then integrated into the 5 m-DEM. We used this updated topographic model for (i) the quantification of the morphometric properties of the study area contributing to the generation of cosmogenic isotopes (area that supplies quartz, see Sect. 3.1), (ii) the establishment of a geomorphic map illustrating the erosional processes within the Gürbe basin, and (iii) the calculation of the catchment-averaged denudation rates from the measured concentrations of the cosmogenic isotopes 10Be, 26Al and 14C.

3.1 Morphometric characterisation

We delineated the different sub-catchment areas in ArcGISPro (v3.1) using the 5 m-DEM as a basis (see previous section). In addition, we computed the sediment connectivity index with the algorithm developed by Borselli et al. (2008) and adapted for alpine catchments by Cavalli et al. (2013). The related algorithm is implemented as an ArcGIS toolbox in ArcMap (v.10.3.1), which we employed accordingly for our study. The sediment connectivity index is based on topographic data and designed to represent the physical connectivity between different areas within an alpine catchment. It thus expresses the probability for sediment, originating in a specific location on a hillslope, to reach the defined targets, such as the main channel or the outlet of a catchment. For the details on the computation we refer to the Sect. 2.1 and 2.2 in Cavalli et al. (2013) where the corresponding Eqs. (1) to (5) are presented.

A compilation of geologic data includes the collection of information on quartz-bearing lithologies, the occurrence of glacial deposits and the extent of the LGM. We gathered such data from three map datasets including (i) the GeoCover (Swisstopo, 2024a) based on Heinz et al. (2023) and Tercier and Bieri (1961), (ii) the Geological Map of Switzerland 1 : 500 000, and (iii) the Map of Switzerland during the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM) 1 : 500 000 (GeoMaps 500 Pixel; Swisstopo, 2024b). Based on this data we grouped the stratigraphic units into quartz-bearing and non-quartz-bearing lithologies (Fig. 1a). As a subsequent step, we corrected the catchment shapes for the occurrence of quartz minerals in bedrock and glacial deposits, thereby clipping the areas with limestone lithologies in the upper part of the catchment where quartz is absent (Figs. 1a, b and 2b).. For the remaining sub-catchments, which contribute to the cosmogenic signals in the channel network because they contain quartz grains, we computed a range of routinely used topographic metrics including slope gradient, terrain ruggedness and channel steepness (e.g., Delunel et al., 2020). Slope gradient and terrain roughness were estimated using tools implemented in ArcGIS (v3.1) pro. We used the terrain ruggedness index (TRI) by Riley et al. (1999) to quantify local terrain variability. This was done by calculating the mean elevation difference between each grid cell and its eight neighbouring cells.

The extraction of river profiles, the calculation of the normalised channel steepness index (ksn) and the mapping of knickpoints was accomplished with the corresponding tools of Topotoolbox (v2.2, Schwanghart and Scherler, 2014). For these calculations, we considered stream segments that have an upstream drainage area > 2000 pixels, and that contribute to the generation of detrital quartz grains. In addition, ksn values were calculated for each cell of the stream network, and then averaged over 125 m-long channel segments, thereby employing a ksn-radius of 500 m. This corresponds to a threshold area of 1000 m2 and a minimum upstream accumulation area of 0.01 km2. As reference concavity we used the default value of θ = 0.45 (Schwanghart and Scherler, 2014).

3.2 Mapping

It has been shown that landsliding, channel incision and overland flow erosion (also referred to as hillslope diffusion in the modelling literature; e.g., Tucker and Slingerland, 1997) are the most important erosional mechanisms contributing to the generation of sediment in a pre-Alpine catchment (Battista et al., 2020). Accordingly, we created an inventory of such processes and potential sediment sources using a variety of methods and data sources. We reconstructed the spatial distribution of landslides through (i) a compilation of already published maps, (ii) an analysis of information available from historical orthophotos, and (iii) observations in the field. Here, we used the landslide inventory from the Natural Hazards Event Catalogue referred to as Naturereigniskataster (Amt für Wald und Naturgefahren des Kantons Bern, 2024) as a basis, which is available from the “Geoportal des Kantons Bern”. We updated this database with information that we retrieved upon analysing historical orthophotos. In this context, the black and white orthophotomosaic images cover the time interval between 1946 and 1998 (SWISSIMAGE HIST; Swisstopo, 2024f). In addition, the time span between 1998 to the present is represented by the three consecutive orthophotomosaics. These latter images have a better spatial resolution than the previous ones (SWISSIMAGE 10 cm; Swisstopo, 2024e). We used these images as a basis to reconstruct the occurrence of topographic changes in the Gürbe catchment over multiple decades. We complemented this dataset with observations on the hillshade DEM, and the maps displaying the slopes and terrain roughness index (TRI) to complete the inventory of landslide occurrence in the study area. We additionally aimed at distinguishing between shallow landslides and thus surficial processes, and deep-seated movements. Shallow landslides, typically covering areas of a few square meters, were identified based on the occurrence of (i) erosion scars resulting in surfaces that are free of vegetation, (ii) small scale depressions in the head of the inferred landslides (“Nackentälchen” according to Haldimann et al., 2017), and (iii) regions characterised by a down-slope increase of the hillslope angle because an escarpment, characterizing the head of a landslide, is typically steeper than the stable area farther upslope (visible in the slope and TRI, see also Schlunegger and Garefalakis, 2023). In contrast, the deep-seated landslides that cover larger areas are characterised by the occurrence of (i) potentially vegetation free areas, (ii) altered vegetation such as sparse or smaller trees with a light colour on the satellite imageries, and (iii) zones of slip that are marked by sharp edges separating a smooth topography above the escarpment edge from an uneven, bumpy terrain below it. Upon mapping landslides, we paid special attention to recognise whether such sediment sources are connected with the channel network, thereby contributing to the bulk sedimentary budget of the Gürbe River.

Incised areas are generally characterised by a V-shaped cross-sectional geometry (Battista et al., 2020). Accordingly, we mapped the upper boundary of such a domain where the landscape is characterised by a distinct break-in-slope. There, the landscape abruptly changes from a gentle morphology above this edge to a steep terrain farther downslope (e.g., Fig. 2C in Cruz Nunes et al., 2015). The steep slopes ending in a channel forming such incisions usually expose the bedrock or the non-consolidated material into which the incision has occurred. Similar to the approach of van den Berg et al. (2012) and Battista et al. (2020), we used the aforementioned criteria to identify such incised areas on the DEM and in the field. Furthermore, we mapped areas where sediment generation has been accomplished through overland flow erosion. In a landscape, such segments are characterised by gentle slopes and smooth transitions between steep and flat areas. They can be readily identified on a hillshade-DEM by their smooth surface texture, lacking evidence for the occurrence of bumps, hollows and scars (van den Berg et al., 2012; Battista et al., 2020). Finally, we also mapped the occurrence of scree deposits (Savi et al., 2015), which occur locally at the base of limestone cliffs. All information were assembled and synthesised in an ArcGIS environment to produce a geomorphic map, illustrating the areas of landslide occurrence.

3.3 Catchment-wide denudation rates inferred from concentrations of cosmogenic 10Be, 26Al and 14C

3.3.1 Sampling strategy and data compilation

During autumn 2022 and spring 2023 we collected a total of seven riverine sand samples at six locations for the analysis of the cosmogenic nuclides 10Be, 26Al and 14C. Each sample consisted of 2–4 kg of sand taken from the active channel bed. We sampled material at those sites where we anticipate capturing the different source signals that result from the various erosional mechanisms (overland flow erosion, incision, and landsliding, see Sect. 3.2). Accordingly, the uppermost sample (C1s) is taken in the Schwändligraben River, which is the main upstream tributary (Fig. 1a). Mapping suggests that at this site the concentration of the cosmogenic isotopes will characterise the signal related to overland flow erosion. A second sample (C3s) was collected in the Gürbe stream just upstream of the confluence with the Schwändligraben River. Similarly to sample C1s, the riverine material taken at site C3s is expected to record a cosmogenic signal related to overland flow erosion, yet it is expected to partially also record the contribution of material derived from the incised area (see Sect. 3.2). We then sampled material from three tributaries draining the area with the deep-seated landslides on the NW orographic left side (samples C6s, C7s and C8s). Finally, we collected two sand samples at the outlet of the catchment and thus at the Gürbe fan apex (C4s and C5s), where the stream starts to flow on the fan. Here, the goal is to characterise the cosmogenic signal representing the mixture of the supplied material from farther upstream. We took one sand sample from the gravel bar close to the active channel and another one from a gravel bar that is situated on the left lateral margin of the Gürbe channel. Upon sampling, we anticipated that fluvial reworking on this second bar – due to its lateral position – has occurred less frequently than material transport in the active channel. In addition, these two separate samples were collected to evaluate the consistency of the mixed sediment signal at the outlet of the catchment.

We also included 10Be concentrations of 5 samples (G1 to G5) collected in 2017 and presented in Delunel et al. (2020) and Latif (2019) in our analysis (Fig. 1a). Site G1 is situated ca. 500 m downstream of the confluence between the Gürbe and Schwändligraben rivers and downstream of the incised area. Accordingly, we anticipate that the 10Be concentration of the riverine sand from this site carries the erosional signal related to the combined effect of overland flow erosion and fluvial incision (van den Berg et al., 2012; Battista et al., 2020). Sites G2 and G3 are located in tributary channels on the orographic left side where sediment has been derived from the landslides. Similarly, to sites C6s to C8s, we expect the concentrations at these sites to characterise the cosmogenic signals related to a material supply from the deep-seated landslides. Site G5 is located on the Gürbe fan apex and is expected to capture the erosional signal of the entire Gürbe catchment. Finally, site G4 is situated in a neighbouring river, which collects the sedimentary material from a drainage basin that is perched on a deep-seated landslide adjacent to the Gürbe catchment farther to the North. We included the 10Be concentration from site G4 in our study because surface erosion in this catchment is not conditioned by the processes of the Gürbe River, thus yielding an independent constrain on denudation occurring in an area where deep-seated landslides have shaped the landscape and contributed to the generation of detrital material.

3.3.2 Laboratory work

The sand samples were sieved to isolate the 250–400 µm grain size fraction. However, due to insufficient material in this size range, the 400 µm–2 mm sand fraction was subsequently crushed and re-sieved to obtain sufficient material with the desired grain size. Further sample processing was performed according to the protocols originally reported in Akçar et al. (2017). The 250–400 µm fraction underwent magnetic separation as a preliminary step, followed by the removal of carbonate minerals trough HCL and successive leaching treatments using hydrofluoric acid, phosphoric acid, and aqua regia to purify the quartz. After measuring the total Al content, additional leaching was performed to further reduce impurities and lower the total Al concentrations. Approximately 40 g of purified quartz was spiked with the 9Be carrier BL-SCH-3 and dissolved in concentrated hydrofluoric acid. Be and Al were stepwise extracted from this solution using anion and cation exchange chromatography, thereby following the protocol of Akçar et al. (2017). The extracted and precipitated Be and Al isotopes were oxidised and pressed into targets for the subsequent measurements of the 10Be 9Be and the 26Al 27Al ratios with the accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) MILEA facility at the ETH Zürich (Maxeiner et al., 2019). The measured 10Be 9Be ratios were normalised with the ETH in-house standard S2007N (Kubik and Christl, 2010) and corrected using a full process blank ratio of 3.92 ± 1.07 × 10−15. The measured 26Al 27Al ratios were normalised to the ETH AMS standard ZAL02N (equivalent to KNSTD, Kubik and Christl, 2010; Christl et al., 2013) and corrected for a small constant background rate. Total Al concentrations, which we measured with the ICP-MS in the aliquot taken from each sample solution, are used to calculate 26Al concentrations from the isotope ratio.

For six samples (C1s, and C3s to C7s) 3 to 4 g of the purified quartz were further processed at the ETH facility for measuring the concentrations of the in-situ 14C (Lupker et al., 2019). The extraction of this isotope was performed following the updated protocol of Hippe et al. (2013). Accordingly, we heated the cleaned quartz in a degassed platinum crucible under ultra-high-purity oxygen to remove contaminants. The 14C isotopes were then extracted by heating the sample to 1650 °C in two cycles for 2 h each, with an intermediate 30 min-long heating step at 1000 °C. The extraction was performed under static O2 pressure in the oven. At the end of the extraction line, the purified CO2 was trapped and flame sealed using LN. The released gas was purified using cryogenic traps and a 550 °C Cu wool oven, and the amount of pure CO2 was measured manometrically before being prepared for the subsequent AMS analysis. CO2 samples were analysed using the MICADAS 200 kV AMS instrument with a gas ion source at the ETH/PSI, which enables the measurement of small carbon samples (2–100 µg C) without requiring graphitization (Synal et al., 2007). The reduction of the AMS data followed the protocols outlined by Hippe et al. (2013) and Hippe and Lifton (2014).

3.3.3 Calculation of denudation rates

We calculated catchment wide denudation rates using the online erosion rate tool formerly known as the CRONUS-Earth calculator (v3, Balco et al., 2008), employing a time independent production scaling (Lal, 1991; Stone, 2000). For the bedrock density, we utilised the widely used value of 2.65 g cm−3. We corrected the scaling calculations for quartz-free regions by using centerpoints and mean catchment elevation derived for only the area that is made up of quartz-bearing lithologies (see above). Following recommendations of DiBiase (2018), no correction for topographic shielding was applied. As shielding due to temporary snow cover leads to a decrease of in-situ cosmogenic nuclide production rates for 26Al and 10Be (e.g., Delunel et al., 2014), we applied a snow cover shielding factor using the empirical approach of Delunel et al. (2020), which itself is based on Jonas et al. (2009). Therein, snow shielding factors were determined as a function of the catchment's mean elevation.

The denudation rates inferred from cosmogenic nuclides are frequently used to estimate the time needed to erode the uppermost 60 cm of material under the assumption of steady state denudation, which is referred to as integration time (Bierman and Steig, 1996; Granger et al., 1996). However, due to landslide perturbations we instead calculated the minimum exposure age as a proxy for the integration time. We thus calculated such time spans for all our nuclide-derived denudation rates, using the same online calculator under the assumption of no erosion and no inheritance.

3.4 Whole-rock geochemical analysis

In order to determine how the supply of sediment from various sources influences the overall sedimentary budget of the Gürbe catchment and the composition of the material in the channel network, we proceeded in a similar way as Glaus et al. (2019), Stutenbecker et al. (2018) and Da Silva Guimarães et al. (2021), measuring the whole rock composition of seven samples (C1s, C3s–C8s). The whole rock geochemical analysis was performed by Actlabs in Canada on sample material before separating the magnetic constituents (see Sect. 3.3.1 above) with grain size < 250 µm. Elements and major oxides were measured in lithium borate fusion glasses through Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometry (ICP-MS). The analytical package included the measurements of the major element oxides: SiO2, Al2O3, Fe2O3, MnO, MgO, CaO, Na2O, K2O, TiO2, P2O5 as well as the trace elements Ba, Sr, Y, Sc, Zr, Be, V. Additional elements Ag, Cd, Cu, Ni, Pb, Zn, S were measured based on multiacid digestion and TD-ICP. Correction was done by the loss of ignition (LOI). We performed a principal component analysis (PCA) with the scikit learn package – implemented in Python (Pedregosa et al., 2011) – on the geochemical data with the aim to identify different source lithologies and to fingerprint potentially different sediment compositions from the individual sub-catchments.

4.1 Mapping, inferred erosional mechanisms and morphometric characterisation

The mapping results allow us to distinguish between three main zones within the Gürbe catchment, which are the upper zone, the lower zone and the fan area (Figs. 1a, 2a and b, 3). The upper zone has predominantly been affected by small, shallow landslides (Fig. 2a). The resulting scars are visible in the historic and current orthoimages. The displaced material has in most cases no obvious connection to the drainage network. Additionally, a few scree deposits exist at the base of limestone cliffs (Figs. 2a, 3a); however, as they are not linked to the drainage network, they do not contribute to the sediment budget of the river network. Overall, the landscape was smoothened by glacial and periglacial processes during the LGM, while the channel network is distinctly defined by its linear geometry (Figs. 2a, 3b). There, channel incision has resulted in the creation of sharp, yet locally constrained escarpments between the hillslopes and the riverbanks. This upper zone is also characterised by a generally low connectivity between the hillslopes and the channel network (Fig. 2c). Except for the spatially disconnected cliffs, the hillslopes are generally gentle to moderately steep (Fig. 3a and b), displaying a mean hillslope angle of 19.2°. In addition, the channel network is characterised by generally low mean normalised steepness values ranging between 26.5 and 30.0 m−0.9 for the two sub-catchments.

In the lower zone, numerous medium- to deep-seated landslides are observed (Figs. 2a, 3d and e). The landscape in this area is characterised by an absence of stable, deeply incised channels, with a channel network instead appearing less well developed. Apparently, the channels adjacent and perched on these landslides have been deflected multiple times during major landslide events (e.g., Simpson and Schlunegger, 2003). In comparison to the upper part, the connectivity between hillslopes and the channel network is higher (Fig. 2c), the hillslopes are generally steeper (mean average hillslope angle of 21.8°), and the tributary and as well as the trunk channels have generally higher steepness values, ranging from 32.4 to 43.4 m−0.9.

The boundary between these two zones is marked by a V-shaped erosional scarp indicating the occurrence of incision (Fig. 3c). This also aligns with the occurrence of the major knickzone along the Gürbe main channel, which is situated at around 1200 m a.s.l and marks the transition reach from the upper to the lower zone (Figs. 1c and 2a). This knickzone reach is readily visible by the change in the steepness values of the channel network, which are higher along the incised reach than upstream and downstream of it.

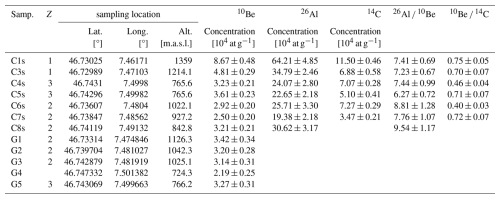

4.2 Cosmogenic nuclide concentrations

The 10Be concentrations in all 12 samples range from the lowest value of 2.50 ± 0.20 × 104 at g−1 with given 2σ uncertainties (resp. 2.19 ± 0.25 × 104 at g−1) measured in the sample G4 to the highest value of 8.67 ± 0.48 × 104 at g−1 measured in the uppermost sample C1 (Table 1 and Table S2 in the Supplement). A comparison of the values across the catchment shows a distinct pattern across the study area. In the upper zone, characterised by sites C1s and C3s (Fig. 1a), the concentrations of in-situ 10Be are up to three times higher than those measured at the outlet of the Gürbe catchment (sites C4s, C5s and G5, Fig. 1a). This pattern suggests a significant supply of sediment with low 10Be concentrations to the Gürbe channel downstream of sites C1s and C3s in addition to the effect related to the differences in the catchment's elevations. The tributaries, characterised by samples taken at sites C6s–C8s, G2 and G3 (Fig. 1a), contribute sediment with concentrations at or below those recorded at the outlet (Table 1), confirming their role as sources of material with lower concentrations. This is also the case for the low 10Be concentration in sample G1 taken downstream of the knickzone, recording a signal that is caused by the large sediment input along the incised area. Additionally, among the three samples taken at the apex of the Gürbe fan, the two samples collected at different times (C4s & G5) show nearly identical 10Be concentrations (3.23 ± 0.21 & 3.27 ± 0.31 × 104 at g−1). Similarly, also the third sample C5s, taken during the same survey as sample C4s but from the margin of the active channel bed, displays a 10Be concentration that is nearly the same (within uncertainties) as the concentrations measured for the two samples from the same location.

Table 1Measured 10Be, 26Al and 14C concentrations for all samples. All uncertainties given are 2σ standard deviation and include the statistical uncertainties of the AMS measurement, the blank error (for 10Be) and the uncertainties of the ICP-MS measurements (for 26Al).

The measured 26Al concentrations show a pattern that is similar to that of 10Be across the catchment. The lowest concentration (19.38 ± 2.18 × 104 at g−1) is recorded in the sample that has also the lowest 10Be value, while the highest 26Al concentration (64.21 ± 4.85 × 104 at g−1) was measured in the same sample that has also the lowest 10Be concentration (material taken from the uppermost site in the catchment; Tables 1 and S3). At the Gürbe fan apex, the two samples collected at different locations show no statistically significant differences in their 26Al concentrations (24.07 ± 2.80 × 104 at g−1 for sample C4s versus 22.65 ± 2.18 × 104 at g−1 for sample C5s).

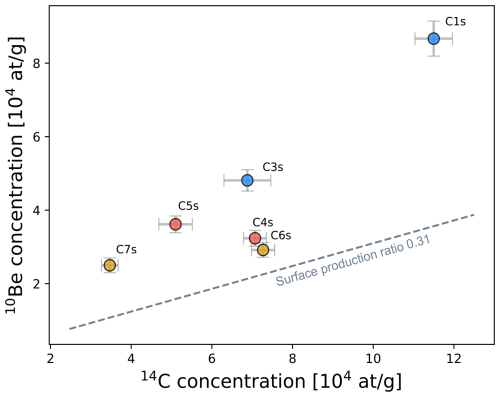

The 14C concentrations of the six sediment samples (C1s, C3s to C7s) range from 3.47 ± 0.21 × 104 to 11.50 ± 0.46 × 104 at g−1 (Tables 1 and S5). While the lowest and highest concentrations are consistently recorded in the same two samples (C7s for the lowest and C1s for the highest concentration), the in-situ 14C concentrations of the other samples display different spatial patterns than the other nuclides. Additionally, the concentrations measured in the two samples at the fan apex significantly differ from each other.

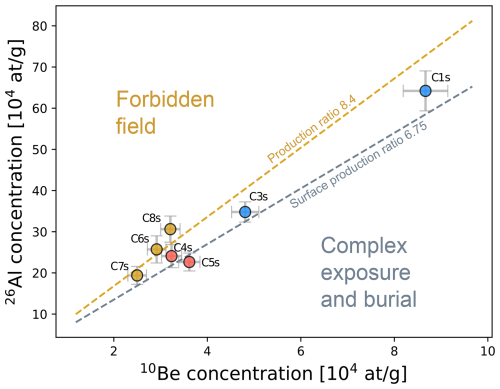

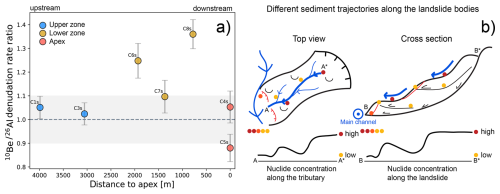

The 26Al 10Be ratios range from 6.27 and 9.54 and, within a 2σ uncertainty. The highest ratios of > 7.76 are observed in the three tributaries. The ratios of 10Be 14C range between 0.40 and 0.75.

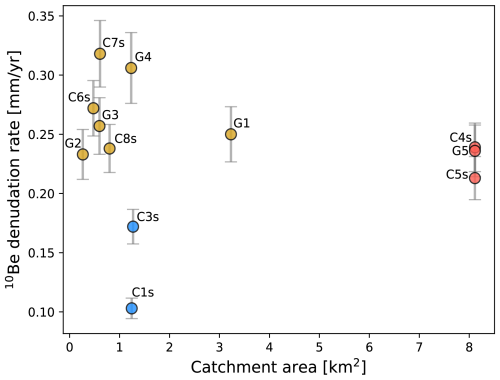

4.3 Denudation rates

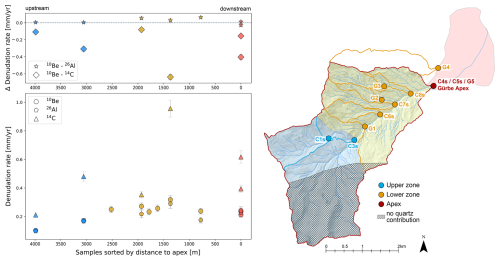

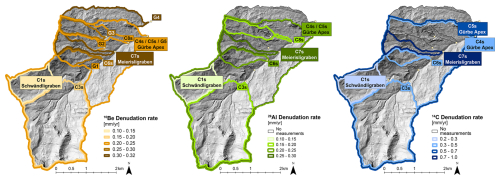

The denudation rates calculated for the three different nuclides are presented in Figs. 4 and 5 (full data available in Table S6) against the upstream distance of the sampling location relative to the Gürbe fan apex. In general, the 10Be-derived denudation rates range from 0.1 to 0.3 mm yr−1 in one of the tributaries. Upstream of the knickzone, the 10Be-based denudation rates are below 0.2 mm yr−1, while downstream of the knickzone, the denudation rates increase to values between 0.2 and 0.3 mm yr−1. A comparison between 10Be- and 26Al-derived denudation rates shows that the rates are the same within uncertainties in the upper catchment, but they differ in the tributaries downstream of the knickzone and at the fan apex. Specifically, 26Al-derived denudation rates are higher than the corresponding 10Be-derived rates at the Gürbe fan apex, whereas in the tributaries they are lower. The 14C-derived denudation rates range from 0.2 to 1.0 mm yr−1. They are thus up 2 to 3 times higher than those derived from the other longer-lived nuclides. The differences Δε between the calculated denudation rates (Fig. 4) range from 0.005 up to 0.06 mm yr−1 (Δε between 26Al- and 10Be-based rates), and from 0.08 up to 0.64 mm yr−1 (Δε between 14C- and 10Be-based rates).

Figure 4Denudation rates calculated based on the measured 10Be, 26Al and 14C concentrations. Each colour indicates the zone represented by the corresponding samples, with blue characterizing the upper zone, yellow the lower zone, and red the Gürbe fan apex. The digital elevation model (DEM) is taken from the Federal Office of Topography swisstopo (Swisstopo, 2024d).

Figure 5Denudation rates calculated based on the 10Be (left), 26Al (middle) and 14C (right) concentrations. The lighter colours illustrate the lowest denudation rates (e.g. the highest concentrations were the sample C1s representing the Schwändligraben sub-catchment in the upper zone). The highest denudation rates were calculated for sample C7s, representing the Meierisligraben tributary in the lower zone. The digital elevation model (DEM) is taken from the Federal Office of Topography swisstopo (Swisstopo, 2024d).

The denudation rates presented above can be used to estimate the timespan over which the cosmogenic data have integrated the erosional processes, which in our case, is approximately 3000 to 6000 years. More specifically, in a zero-erosion scenario, the minimum duration of exposure required to accumulate the measured 10Be and 26Al concentrations ranges from 2000 to 6000 years, while for 14C concentrations it ranges from 800 to 3000 years (Table S6).

4.4 Geochemical composition of sediment

The analysed samples showed variable SiO2 contents (33 wt %–58 wt %) and Al2O3 (5 wt %–12 wt %), which are anticorrelated with CaO concentrations (8 % to 29 %; Table S6). Here, the samples from catchments with limestone-bearing lithologies (e.g. C3s; Fig. 2) show the highest concentrations of CaO and the lowest ones of SiO2 and Al2O3 (Table S6), resulting in a pattern where the CaO concentrations decrease in the downstream direction. This reflects the corresponding trend in exposed lithologies where the relative proportion of limestones in the basin decreases downstream. The relative abundance of all other major oxides varies significantly between individual samples (Table S6). Similarly, the concentrations of the trace elements did not vary strongly, with the main trace elements being Sr (325 to 717 ppm), Ba (140 to 310 ppm) and Zr (90 to 220 ppm). Apart from the downstream-decreasing trend of geochemical signals associated with limestone lithologies (Penninic Klippen Belt) – relative to those indicative of SiO2- and Al2O3-rich bedrock (Flysch and Molasse units) – no systematic variation in geochemical composition is observed, either for the major oxides or for the trace elements (Fig. S1).

The concentrations of the cosmogenic isotopes 10Be and 26Al and the resulting denudation rates show distinct differences between the upper, gently sloping region and the lower, steeper zone of the catchment (Figs. 4 and 5). We first discuss the implications of this pattern and particularly explore how the cosmogenic signals within the Gürbe basin change in the downstream direction as sediments derived from landslides impact the cosmogenic signal towards the catchment's outlet near the fan apex (Sect. 5.1). Next, we combine the 10Be, 26Al, and 14C datasets to investigate the erosional dynamics across different temporal scales. By comparing the signals preserved by these isotopes, we assess whether the cosmogenic nuclide concentrations reflect the occurrence of steady erosion over varying timescales, or if they record the effects of inheritance, burial, or transient perturbations over the same timescales (Sect. 5.2 and 5.3). As a next aspect, we discuss (i) how the cosmogenic nuclide-based denudation rates relate to the landscape's architecture by comparing them with the mapping results (Sect. 5.4), and (ii) how this pattern has been conditioned by the glacial carving during the past glaciations (Sect. 5.5). We end the discussion with a notion that in drainage basins where the bedrock is too homogeneous to pinpoint the origin of the detrital material, terrestrial cosmogenic nuclides offer a viable tool for provenance tracing (Sect. 5.6).

5.1 Downstream propagation and scale dependency of cosmogenic signals

The 10Be and 26Al concentrations, and consequently the inferred denudation rates, record the occurrence of a variety of erosional mechanisms across the Gürbe basin. In the upper part of the catchment, high cosmogenic nuclide concentrations correspond to low denudation rates. This contrasts with the lower nuclide concentrations and higher denudation rates inferred for the samples collected in the tributaries of the lower zone, along the incised reach downstream of the knickzone (sample G1), and at the fan apex (Fig. 6). This downstream decrease in concentrations of both nuclides suggests that the pattern of sediment generation has been stable over the erosional timescale recorded by them. Such an interpretation is corroborated by the same nuclide concentrations (within uncertainties) encountered in the three riverine samples at the fan apex. This is surprising because sediment supply through landsliding – in our case in the lower zone – introduces a stochastic variability into the generation of sediment. Such a mechanism was already demonstrated for other Alpine torrents (Kober et al., 2012; Savi et al., 2014), where stochastic processes such as landslides and debris flows have resulted in episodic supply of sediment with low 10Be concentrations (Niemi et al., 2005; Kober et al., 2012). This has the potential to perturb the overall cosmogenic signal particularly in small catchments (Yanites et al., 2009; Marc et al., 2019), thereby (i) leading to variations in nuclide concentrations within riverine sediments collected from the same channel bed (Binnie et al., 2006) and (ii) introducing scatter into the dataset (DiBiase et al., 2023). Given the small area (12 km2) and the prevalence of recurrent landslides in the Gürbe sub-catchments, one might expect the sedimentary material at the Gürbe fan apex to record such variations. Yet our results indicate that the overall denudation signal has remained nearly stable at the fan apex (Fig. 6). This highlights an important scale-dependency in the erosional controls governing the generation of cosmogenic signals in the Gürbe basin. In particular, at smaller spatial scales (0.25–3.5 km2), denudation rates reflect the controls of local geomorphic and geologic conditions on erosion and material supply, such as repeated deep-seated landsliding as in the case presented here. However, when these signals with a local origin are aggregated downstream towards the fan apex, they are recorded as a mixed, more stable signal that averages out the high and low concentrations generated in the individual sub-catchments. In the Gürbe basin, such mixing appears to occur at a spatial scale of less than 10 km2. We thus infer – as this has already been mentioned by the many studies referred to in this paper in previous sections – that cosmogenic nuclides remain a suitable tool for estimating long-term average erosion rates over thousands of years for landscapes that have been eroded at rates between 0.1 and < 1 mm yr−1 (von Blanckenburg, 2005). This holds true even for catchments influenced by repeated stochastic processes – such as those documented for landslide processes in the Gürbe basin – provided that the sediment is sufficiently well mixed and that the corresponding cosmogenic nuclides are in an isotopic steady state (Clapuyt et al., 2019).

Figure 6Scale dependency of denudation rate estimates with concentrations of in-situ 10Be. The variety of denudation rates determined for the scales of small local catchments (blue for the upper zone and yellow for the lower zone) is averaged out for the samples collected at the fan apex (red) where concentrations of in-situ 10Be characterise the mixed erosional signal of the entire catchment and thus for a larger scale.

5.2 Steadiness of the denudation signals across time scales

Concentrations of cosmogenic nuclides in riverine quartz have the potential to record the erosional history of a landscape, provided that (i) the nuclide production has occurred at a steady rate across the spatio-temporal scale over which they integrate erosion rates, and (ii) the nuclides are saturated (e.g., von Blanckenburg, 2005). A potential deviation from these assumptions could be caused by a sedimentary legacy from past glaciations (Jautzy et al., 2024). This also concerns the Gürbe basin, as the study area has a history of erosion and material deposition by local and regional glaciers – most notably by the Aare glacier. The coverage of the surface by glaciers could have led to transient shielding of the surface during glacial times, potentially distorting the cosmogenic isotope signal (Slosson et al., 2022). Yet our 10Be and 26Al-based denudation rates point to an integration time < 8000 years, whereas for 14C, it is even shorter with < 3000 years (Table S6). These ages are significantly younger than the last major glacial advance at around 12–11 ka ago (Ivy-Ochs et al., 2009). Therefore, we conclude that a potential inheritance from pre-glacial surfaces does not significantly affect our data for all nuclides.

A further potential bias in quantifying denudation rates with cosmogenic nuclides could be introduced through sediment storage and reworking along the sediment cascade (e.g., Wittmann et al., 2020; Halsted et al., 2025). However, the ratios of the 10Be and 26Al concentrations are close to the values characterizing a nuclide production close to the surface (Fig. 7). Additionally, the resulting denudation rates are overall in good agreement with each other, at least in the upper zone and at the basin's outlet. This suggests that the 10Be and 26Al concentrations do not record the occurrence of a significant erosional transience during the past millennia, at least if the nuclide concentrations in the samples from the upper zone and the downstream end of the Gürbe basin are considered. We therefore consider, and this has already been noted in the previous section, that the signals preserved by the concentrations of in-situ 10Be and 26Al do record a pattern of erosion and sediment generation that has been stable at least during the erosional timescale of both isotopes, which are several thousand years. We acknowledge, that in the lower zone the supply of material through landsliding does result in a measurable discrepancy between the 10Be and 26Al-based denudation rates (Figs. 4, 6 and 7), a pattern which is discussed in Sect. 5.4. We also note that the denudation rate pattern of the short-lived 14C is distinctly different from that of 10Be and 26Al, which renders interpretations thereof more complex (see next Sect. 5.3).

Figure 7Two-nuclide diagram showing the 10Be concentrations versus the 26Al concentrations. The 26Al concentration is plotted against the 10Be concentration. The concentrations are within the field that is characteristic for a nuclide production on the surface. The occurrence of long-term burial can be excluded for our samples. See Fig. 4 for location of the zones, respective samples, and corresponding color coding.

5.3 Potential controls on the pattern of cosmogenic 14C

Here, we present several arguments as to why the pattern of 14C concentrations in the riverine sediments of the Gürbe basin is not straightforward to explain. First, as outlined by Hippe (2017), in cases where the signal integration timespan exceeds the half-life of the corresponding cosmogenic isotope, a portion of the accumulated radionuclides will decay before the material is completely eroded. The result is a reduction of the 14C concentrations, which could lead to an artificially high erosion rate (Hippe, 2017). In our case, the minimum exposure time required to accumulate the observed 14C concentrations is less than 3000 years – well below the isotope's half-life of 5730 years. This makes unaccounted radioactive decay an unlikely primary cause of the low 14C concentrations in our samples. Second, a recent change in erosion rates on timescales shorter than the signal integration-time of 10Be and 26Al could explain why the 14C-based denudation rates are up to three times higher than the estimates derived from the other isotopes. This would require a scenario where the 14C signal is already recording this increase in erosion, while the concentrations of 10Be and 26Al have not yet registered such a change. However, in rapidly eroding landscapes (> 500 mm kyr−1) 10Be concentrations initially adjust more rapidly to changes in erosion rates than 14C concentrations (Skov et al., 2019). This difference arises from the higher muogenic production of 14C at depth, which can cause a temporary increase of 14C concentrations relative to 10Be in freshly exposed bedrock and detrital material during periods of accelerated erosion. As a consequence, an acceleration of erosion can only be reliably detected several thousand years after the change (Skov et al., 2019; see also Mudd, 2017). The exact duration of this latency depends on both the magnitude and timing of the perturbation that caused the change. In other words, a scenario in which a period of accelerated erosion began several thousand years ago could explain why some 14C-based denudation rates are higher than those derived from the other two nuclides. Yet, it does not explain the relative differences in 14C-based denudation rates between the sampled catchments (Figs. 4 and 5). Particularly, the pattern is not consistent throughout any of the three zones, and the denudation rate variation within the zones is higher than the variation between the zones (Fig. 4). This would require a scenario in which the increase in erosion rates was different in magnitude and timing across all sub-catchments. Therefore, the inconsistent spatial pattern, along with greater within-zone than between-zone variations, suggests that the observed changes in 14C concentrations cannot be explained solely by an increase in erosion rates. Third, geomorphic processes such as soil mixing or intermittent sediment storage during transport could in part explain the observed differences between the 14C and 10Be 26Al-derived denudation rates. In particular, sediment could be stored – e.g., in response to landsliding – below the production zone of 14C, during which the 14C inventory is partially lost due to the radioactive decay of this isotope (Hippe et al., 2012; Kober et al., 2012; Hippe, 2017; Skov et al., 2019). Such a process has been referred to as transient shielding by Slosson et al. (2022). Because the 10Be 14C ratios in the Altiplano samples range between 3.6 and 15.2 – significantly higher than the surface production ratio of 0.31 – Hippe et al. (2012) interpreted the relatively low 14C concentrations in the riverine sediments as a record of storage rather than surface erosion. However, since the 10Be 14C ratios of the riverine samples in the Gürbe basin range from 0.4 to 0.75 (Fig. 8) and thus do not fully fall within the complex exposure field, we consider it unlikely that the 14C concentrations primarily reflect a signal of sedimentary storage. Furthermore, in the upper zone of the Gürbe basin, we exclude the occurrence of widespread storage following sediment mobilization, as there is no evidence in the landscape that such processes have taken place (e.g., the presence of large sedimentary bodies along the channels or talus cones as was reported by Slosson et al. (2022) from their study area). In summary, while 14C has the potential to provide valuable insights into shifts in erosional dynamics, sediment storage, and episodic mobilization of material from deeper levels (Hippe et al., 2012; Hippe, 2017), we are unable to conclusively determine the specific processes responsible for the observed pattern of 14C concentrations and denudation rates in the Gürbe basin.

Figure 8Two-nuclide diagram showing the 10Be concentrations versus the 14C concentrations. The 10Be concentration is plotted against the 14C concentration in relation to the surface production rate of 0.31 × 104 at g−1 (Hippe et al., 2012). See Fig. 4 for location of the zones, respective samples, and corresponding color coding.

5.4 Landscape architecture and corresponding 10Be and 26Al signals

The comparison of the geomorphic map with the 10Be and 26Al concentrations and the calculated denudation rates exhibits a distinct difference between the upper and lower zone, each characterised by specific topographic features and dominant erosional processes. Specifically, the landscape in the upper zone of the Gürbe catchment is characterised by smooth slopes and the occurrence of partly incised channels with low steepness values and a low connectivity to the hillslopes. Such properties are characteristic for a landscape where overland flow erosion, also referred as hillslope diffusion according to Tucker and Slingerland (1997), have controlled the generation of clastic sedimentary material (van den Berg et al., 2012). The high cosmogenic nuclide concentrations and, as consequence, the low denudation rates together with the 26Al 10Be concentration ratios of 7.41 ± 0.69 and 7.23 ± 0.67 – that are close to the surface production ratio of 6.75 (Nishiizumi et al., 1989; Balco et al., 2008) – are consistent with such an interpretation (Fig. 7). The similarity in the denudation rates calculated for the two long-lived nuclides supports the interpretation of an erosional regime without significant perturbations (Fig. 9a), at least for the time scale of thousands of years as recorded by both isotopes. We note that shallow landslides and localised rockfall do occur in this upper zone, but the resulting deposits are partly disconnected from the channel network, thereby minimizing their impact on the sediment budget of the Gürbe catchment (Figs. 2 and 3). In contrast, the lower zone exhibits a more dynamic erosional regime, where steeper slopes (20 to 25°) together with the predominant occurrence of mudstones in the Flysch and Upper Marine Molasse bedrock (Diem, 1986) offer ideal conditions for the displacement of medium- to deep-seated landslides. Mapping also shows that landslides have impacted the sediment budget of the Gürbe River either through direct material supply into the main channel, where material is subsequently remobilised and transported downstream, or through erosion of landslide bodies by tributary streams and associated hillslope processes such as overland flow erosion and shallow-seated landslides, thereby reworking the previously displaced material. In general, such stochastic processes result in episodic sediment inputs with relatively low 10Be concentrations, as material is exhumed fast from greater depths (e.g., Niemi et al., 2005). In the Gürbe basin, however, most landslides have remained dormant for decades, but have regularly been re-activated with slip rates of several meters per day. These re-activations have resulted in the excavation of material along multiple trajectories from depth to the surface, and finally to the channel network. The mixing of material from different exposure trajectories (Fig. 9b) most likely explains the relatively high 26Al 10Be concentration ratios between 7.76 ± 1.07 to 9.54 ± 1.17 (Fig. 6) that we determined for the riverine material in three tributaries with material sources in these landslides. The discrepancy between the 10Be- and 26Al-based denudation rates – with ratios ranging from 1.1 to 1.4 – is a further support of the inferred complex erosional history along the sediment cascade (Fig. 9a). These findings demonstrate that the occurrence of landsliding not only results in an overall increase of erosion rates but also introduces a variability in the cosmogenic 26Al 10Be concentration ratios. Yet, if such cycles of landslide quiescence and activity have occurred multiple times and at different locations in a basin, the resulting cosmogenic concentrations will converge to a stable cosmogenic signal farther downstream and thus for a large spatial scale. This is the case for the outlet of the Gürbe basin where we determine consistent cosmogenic nuclide signals. This implies that at the scale of individual tributary basins, which is < 2 km2 in our case, the production of sediment can be highly stochastic. At the scale of an entire basin – in our case the Gürbe basin with a size of 8 km2 – the ensemble of the stochastic processes converges to a sediment cascade that can be characterized as steady state, at least for the time scale recorded by the cosmogenic isotopes.

Figure 9Sediment cascade in the Gürbe basin recorded by cosmogenic nuclides. (a) Ratios between 26Al- and 10Be-based denudation rates. In the upper zone the ratios between the denudation rate calculated with both isotopes are in very good agreement. In the lower zone the 26Al-based denudation rates are lower than the 10Be-based rate, leading to ratios that are larger than one. At the fan apex the ratios between both rates are in a relatively good agreement. The grey shading is representing the ±10 % envelope of the isotope ratio. (b) conceptual model of different sediment trajectories along the medium- to deep-seated landslide bodies leading to lower nuclide concentrations in tributaries.

5.5 The importance of glacial conditioning as an erosional driving force

In a previous study, Delunel et al. (2020) showed that a large part of the catchment-averaged denudation rates in the European Alps can be understood as a diffusion-type of process – or a mechanism which we refer to as overland flow erosion following Battista et al. (2020) – where denudation rates increase with mean-basin hillslope angles until a threshold hillslope angle of 25–30° (Schlunegger and Norton, 2013). Because the hillslope angles in the Gürbe catchment are below the 25° threshold, one would predict an erosional signal that could be explained by such a mechanism. While all our denudation rates do fall in the corresponding range of denudation rates (cf. Fig. 5 of Delunel et al., 2020) and since such an assignment is certainly correct for the upper part of the Gürbe catchment (Sect. 5.4), the lower zone deviates from this acknowledgably useful categorization. Indeed, despite the slopes being flatter than 25°, erosion in this region has been dominated by deep-seated landslides that are perched by a channel network. Such a combination of processes has typically been reported for landscapes steeper than 30° in the European Alps (Delunel et al., 2020) and other mountain ranges, e.g. the San Gabriel Mountains (DiBiase et al., 2023). This difference of erosion highlights the importance of another driving force than lithology alone because Flysch bedrock also occurs in the upper zone where landslides are largely absent, but where the hillslopes are less steep. Because the elevation of the knickzone separating the upper from the lower zones corresponds to the level of the LGM Aare glacier in this region (Bini et al., 2009), it is possible that the formation of the knickzone along the Gürbe River was conditioned by glacial carving during the LGM and possibly previous glaciations. Accordingly, the relatively flat channel and hillslope morphology in the area upstream of the knickzone could be explained by damming effects related to the presence of the Aare glacier. In contrast, the shape of the topography downstream of the knickzone was most likely conditioned by erosion along the lateral margin of the Aare glacier. Accordingly, the formation of a relatively steep flank could explain why the course of the Gürbe River is steeper than would be expected for a river with a same catchment size (do Prado et al., 2024), and why erosion on the hillslopes has been dominated by landsliding instead of overland flow erosion. Similar controls were already proposed by Norton et al. (2010) and van den Berg et al. (2012) upon explaining the occurrence of landscapes dominated by gentle hillslopes upstream of glacially conditioned knickzones and steeper hillslopes downstream of them. In such a context, a lowering of the base level after the retreat of the LGM glacier would have initiated a wave of headward erosion, with the consequence that the entire catchment is in a transient stage of landscape evolution (Abbühl et al., 2011; Vanacker et al., 2015). Accordingly, while the Gurnigel Flysch and Lower Marine Molasse bedrock seem to promote the occurrence of deep-seated landslides – thus overriding the expected overland flow-controlled behaviour typically observed in catchments with similar slopes elsewhere – a steepening of the landscape due to glacial carving needs also be considered as an additional condition accelerating erosion in the lower part of the basin.

5.6 Geochemical composition of the detrital material, and the use of cosmogenic isotopes for provenance tracing

The whole rock geochemical analysis discloses a picture that is characteristic for a basin where limestones and sandstones are the main lithological constituents, as already demonstrated by Glaus et al. (2019) and Da Silva Guimarães et al. (2021) for other basins in the Alps. Yet, in contrast to the aforementioned studies, the results of our research did not allow a differentiation of the erosional signals derived from the various parts of the Gürbe basin, because here the only difference in composition among the samples seems to relate to the relative proportion of limestone constituents in the detrital material (Sect. 4.4). However, the outcropping limestone units are only present locally in some of the headwater reaches (Fig. 2). This introduces a potential limitation: while our quartz-based cosmogenic nuclide measurements provide valuable erosion rate estimates, they are inherently blind to sediment generated from quartz-free lithologies, such as limestones. This raises the question of how well the total sediment load and the erosion rates – the latter ones inferred from the cosmogenic nuclide data – are in agreement with each other. In particular, high erosion rates in the headwater areas made up of limestones could lead to a high relative abundance of limestone grains in the Gürbe sediments farther downstream. This, in turn, could result in an underestimation of the effective denudation rates if such budgets are only based on cosmogenic isotopes. However, in our case, we observe only a limited contribution of the limestone lithologies to the sediment budget of the entire Gürbe basin as we do not – except for the pattern of CaO relative to SiO2 and Al2O3 – see any systematic variation in the geochemical composition of the detrital material. We therefore consider our cosmogenic-based erosion rates as representative – particularly as we use them to map spatial variations in the generation of sediment across the basin. Additonally, and more important, the use of paired nuclides – in our case 26Al to 10Be – yields conclusive information on the origin of the detrital material as sediments derived from landslides and thus from deeper levels tend to have a higher ratio between the concentrations of both isotopes than sedimentary particles generated through overland flow erosion alone (Akçar et al., 2017; Dingle et al., 2018; Knudsen et al., 2020). Accordingly, this study demonstrates that concentrations of cosmogenic isotopes offer suitable information for allocating the source of sediments in drainage basins where other provenance tracing methods, in our case whole-rock geochemical compositions of the riverine material, yield non-conclusive results. Here, we demonstrate that such an approach to trace the origin of the material holds even in a basin where the spatial contrasts in measured erosion rates are relatively low. In such cases, a reconstruction of both the sediment sources and the associated erosional mechanisms requires a dense sampling strategy, as implemented in this work – a need that was already emphasised by Clapuyt et al. (2019) and Battista et al. (2020).

This study demonstrates that cosmogenic nuclides are ideal tracers for identifying the origin of detrital material in basins with spatially varying erosion rates. They not only allow us to determine the region where most sediment has been generated, but also yield crucial information to reconstruct the mechanisms through which erosion has occurred (e.g., overland flow erosion versus landsliding), particularly when multiple isotopes are used. In the Gürbe basin, we were able to reconstruct such patterns and mechanisms using concentrations of in-situ 10Be and 26Al measured in riverine quartz. However, the concentrations of in-situ 14C, which we also measured in the same samples, yielded non-conclusive results. Also in the Gürbe basin, we found that the erosional processes were different in the upper zone above the LGM trim line where the landscape is flat and sediment generation has been dominated by overland flow erosion, and in the region below it where the landscape is steeper and erosion has been accomplished by landsliding and fluvial incision. This points to a legacy of the current erosional mechanisms stemming from the glaciations, where carving of the valley flanks by the LGM (Late Glacial Maximum) and earlier glaciers steepened the landscape, thereby promoting erosion below the LGM margin following the glaciers' retreat. This initiated a wave of headward retreat and the formation of an erosional front separating an upper part with low erosion rates (overland flow erosion) from a lower part where erosion occurs more rapidly and has mainly been accomplished by landsliding. In the Gürbe basin, we identified this erosional front through the occurrence of a distinct knickzone in the longitudinal stream profile. This phase of headward retreat thus suggests that the Gürbe basin has been in a long-term transient state of topographic development where the current accelerated erosion and landsliding in the lower zone has been glacially conditioned. Yet despite this transient state of basin development, we find – based on the concentrations of cosmogenic 10Be and 26Al in the riverine material – that the pattern and rate of sediment generation has been quite stable and thus steady during the past thousands of years. This was surprising because landslides have the potential to introduce a stochasticity in the way of how erosion and sediment generation occurs. It thus appears that the transient adjustment of the Gürbe basin to post-glacial conditions has occurred in a near-steady, possibly self-organised way, resulting in sediment generation, which has occurred at nearly constant rates at least during the past thousands of years. Because cosmogenic 26Al and 10Be integrate erosional signals over millennia in the Gürbe basin – including periods during which environmental conditions have changed – we expect a similar pattern of sediment generation and transfer in the near future, even under the current warming climate. Consequently, in the near future, the local authorities are likely to face the same sediment transfer mechanisms through the basin and the cascade of check dams as those occurring today.

All data used in this study are provided in tables or included in the Supplement. The swisstopo digital elevation models (DEMs) are publicly available (https://www.swisstopo.admin.ch/en/height-model-swissalti3d, Swisstopo, 2024d).

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-14-33-2026-supplement.

CS designed the study, conducted the analyses and wrote the paper with support by FS, DM and BM. NA offered scientific advise during sample collection and preparation, and during the analysis of the AMS results. MC, CV, PG supervised the AMS measurements of 26Al and 10Be and offered support for the interpretation of the MS data. NH performed the in-situ 14C extraction and measured the 14C concentrations. All authors contributed to the scientific processing and discussion of the results and to the drafting of the paper.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We thank Julijana Gajic for training and supervising the lab work at the IFG as well as Priska Bähler for the total Al measurements. This work was funded through the Trebridge project funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF project no. 205912).

This research has been supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation SNSF (grant no. 205912).

This paper was edited by Joris Eekhout and reviewed by Richard Ott and one anonymous referee.

Abbühl, L. M., Norton, K. P., Jansen, J. D., Schlunegger, F., Aldahan, A., and Possnert, G.: Erosion rates and mechanisms of knickzone retreat inferred from 10 Be measured across strong climate gradients on the northern and central Andes Western Escarpment, Earth Surf. Process. Landforms, 36, 1464–1473, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.2164, 2011.

Akçar, N., Ivy-Ochs, S., Alfimov, V., Schlunegger, F., Claude, A., Reber, R., Christl, M., Vockenhuber, C., Dehnert, A., Rahn, M., and Schlüchter, C.: Isochron-burial dating of glaciofluvial deposits: First results from the Swiss Alps, Earth Surf. Process. Landforms, 42, 2414–2425, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4201, 2017.

Amt für Wald und Naturgefahren des Kantons Bern: Naturgefahrenkataster (NGKAT), https://www.agi.dij.be.ch/de/start/geoportal/geodaten/detail.html?type=geoproduct&code=NGKAT (last access: 26 May 2025), 2024.

Balco, G., Stone, J. O., Lifton, N. A., and Dunai, T. J.: A complete and easily accessible means of calculating surface exposure ages or erosion rates from 10Be and 26Al measurements, Quaternary Geochronology, 3, 174–195, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2007.12.001, 2008.

Battista, G., Schlunegger, F., Burlando, P., and Molnar, P.: Modelling localized sources of sediment in mountain catchments for provenance studies, Earth Surf. Process. Landforms, 45, 3475–3487, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4979, 2020.

Bierman, P. and Steig, E.: Estimating rates of denudation using cosmogenic isotope abundances in sediment, Earth Surf. Process. Landforms, 21, 125–139, 1996.

Bini, A., Buonchristiani, J.-F., Couterand, S., Ellwanger, D., Felber, M., Florineth, D., Graf, H. R., Keller, O., Kelly, M., Schlüchter, C., and and Schöneich, P.: Die Schweiz während des letzteiszeitlichen Maximums (LGM), https://www.swisstopo.admin.ch/de (last access: 6 December 2024), 2009.

Binnie, S., Phillips, W., Summerfield, M., and Fifield, K.: Sediment mixing and basin-wide cosmogenic nuclide analysis in rapidly eroding mountainous environments, Quaternary Geochronology, 1, 4–14, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.quageo.2006.06.013, 2006.

Borselli, L., Cassi, P., and Torri, D.: Prolegomena to sediment and flow connectivity in the landscape: A GIS and field numerical assessment, CATENA, 75, 268–277, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2008.07.006, 2008.

Brardinoni, F., Grischott, R., Kober, F., Morelli, C., and Christl, M.: Evaluating debris-flow and anthropogenic disturbance on 10 Be concentration in mountain drainage basins: implications for functional connectivity and denudation rates across time scales, Earth Surf. Process. Landforms, 45, 3955–3974, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.5012, 2020.