the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Estimates of late Cenozoic climate change relevant to Earth surface processes in tectonically active orogens

Sebastian G. Mutz

Todd A. Ehlers

Martin Werner

Gerrit Lohmann

Christian Stepanek

Jingmin Li

The denudation history of active orogens is often interpreted in the context of modern climate gradients. Here we address the validity of this approach and ask what are the spatial and temporal variations in palaeoclimate for a latitudinally diverse range of active orogens? We do this using high-resolution (T159, ca. 80 × 80 km at the Equator) palaeoclimate simulations from the ECHAM5 global atmospheric general circulation model and a statistical cluster analysis of climate over different orogens (Andes, Himalayas, SE Alaska, Pacific NW USA). Time periods and boundary conditions considered include the Pliocene (PLIO, ∼ 3 Ma), the Last Glacial Maximum (LGM, ∼ 21 ka), mid-Holocene (MH, ∼ 6 ka), and pre-industrial (PI, reference year 1850). The regional simulated climates of each orogen are described by means of cluster analyses based on the variability in precipitation, 2 m air temperature, the intra-annual amplitude of these values, and monsoonal wind speeds where appropriate. Results indicate the largest differences in the PI climate existed for the LGM and PLIO climates in the form of widespread cooling and reduced precipitation in the LGM and warming and enhanced precipitation during the PLIO. The LGM climate shows the largest deviation in annual precipitation from the PI climate and shows enhanced precipitation in the temperate Andes and coastal regions for both SE Alaska and the US Pacific Northwest. Furthermore, LGM precipitation is reduced in the western Himalayas and enhanced in the eastern Himalayas, resulting in a shift of the wettest regional climates eastward along the orogen. The cluster-analysis results also suggest more climatic variability across latitudes east of the Andes in the PLIO climate than in other time slice experiments conducted here. Taken together, these results highlight significant changes in late Cenozoic regional climatology over the last ∼ 3 Myr. Comparison of simulated climate with proxy-based reconstructions for the MH and LGM reveal satisfactory to good performance of the model in reproducing precipitation changes, although in some cases discrepancies between neighbouring proxy observations highlight contradictions between proxy observations themselves. Finally, we document regions where the largest magnitudes of late Cenozoic changes in precipitation and temperature occur and offer the highest potential for future observational studies that quantify the impact of climate change on denudation and weathering rates.

- Article

(7504 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(959 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Interpretation of orogen denudation histories in the context of climate and tectonic interactions is often hampered by a paucity of terrestrial palaeoclimate proxy data needed to reconstruct spatial variations in palaeoclimate. While it is self-evident that palaeoclimate changes could influence palaeodenudation rates, it is not always self-evident what the magnitude of climate change over different geologic timescales is, or what geographic locations offer the greatest potential to investigate palaeoclimate impacts on denudation. Palaeoclimate reconstructions are particularly beneficial when denudation rates are determined using geo- and thermo-chronology techniques that integrate over timescales of 103–106+ years (e.g. cosmogenic radionuclides or low-temperature thermochronology; e.g. Kirchner et al., 2001; Schaller et al., 2002; Bookhagen et al., 2005; Moon et al., 2011; Thiede and Ehlers, 2013; Lease and Ehlers, 2013). However, few studies using denudation rate determination methods that integrate over longer timescales have access to information about past climate conditions that could influence these palaeodenudation rates. Palaeoclimate modelling offers an alternative approach to sparsely available proxy data for understanding the spatial and temporal variations in precipitation and temperature in response to changes in orography (e.g. Takahashi and Battisti, 2007a, b; Insel et al., 2010; Feng et al., 2013) and global climate change events (e.g. Salzmann et al., 2011; Jeffery et al., 2013). In this study, we characterise the climate at different times in the late Cenozoic and the magnitude of climate change for a range of active orogens. Our emphasis is on identifying changes in climate parameters relevant to weathering and catchment denudation to illustrate the potential importance of various global climate change events on surface processes.

Previous studies of orogen-scale climate change provide insight into how different tectonic or global climate change events influence regional climate change. For example, sensitivity experiments demonstrated significant changes in regional and global climate in response to landmass distribution and topography of the Andes, including changes in moisture transport, the north–south asymmetry of the Intertropical Convergence Zone (e.g. Takahashi and Battisti, 2007a; Insel et al., 2010), and (tropical) precipitation (Maroon et al., 2015, 2016). Another example is the regional and global climate changes induced by the Tibetan Plateau surface uplift due to its role as a physical obstacle to circulation (Raymo and Ruddiman, 1992; Kutzbach et al., 1993; Thomas, 1997; Bohner, 2006; Molnar et al., 2010; Boos and Kuang, 2010). The role of tectonic uplift in long-term regional and global climate change remains a focus of research and continues to be assessed with geologic datasets (e.g. Dettman et al., 2003; Caves, 2017; Kent-Corson et al., 2006; Lechler et al., 2013; Lechler and Niemi, 2011; Licht et al., 2017; Methner et al., 2016; Mulch et al., 2015, 2008; Pingel et al., 2016) and climate modelling (e.g. Kutzbach et al., 1989; Kutzbach et al., 1993; Zhisheng, 2001; Bohner, 2006; Takahashi and Battisti, 2007a; Ehlers and Poulsen, 2009; Insel et al., 2010; Boos and Kuang, 2010). Conversely, climate influences tectonic processes through erosion (e.g. Molnar and England, 1990; Whipple et al., 1999; Montgomery et al., 2001; Willett et al., 2006; Whipple, 2009). Quaternary climate change between glacial and interglacial conditions (e.g. Braconnot et al., 2007; Harrison et al., 2013) resulted in not only the growth and decay of glaciers and glacial erosion (e.g. Yanites and Ehlers, 2012; Herman et al., 2013; Valla et al., 2011) but also global changes in precipitation and temperature (e.g. Otto-Bliesner et al., 2006; Li et al., 2017) that could influence catchment denudation in non-glaciated environments (e.g. Schaller and Ehlers, 2006; Glotzbach et al., 2013; Marshall et al., 2015). These dynamics highlight the importance of investigating how much climate has changed over orogens that are the focus of studies of climate–tectonic interactions and their impact on erosion.

Despite recognition by previous studies that climate change events relevant to orogen denudation are prevalent throughout the late Cenozoic, few studies have critically evaluated how different climate change events may, or may not, have affected the orogen climatology, weathering, and erosion. Furthermore, recent controversy exists concerning the spatial and temporal scales over which geologic and geochemical observations can record climate-driven changes in weathering and erosion (e.g. Whipple, 2009; von Blanckenburg et al., 2015; Braun, 2016). For example, the previous studies highlight that although palaeoclimate impacts on denudation rates are evident in some regions and measurable with some approaches, they are not always present (or detectable) and the spatial and temporal scale of climate change influences our ability to record climate-sensitive denudation histories. This study contributes to our understanding of the interactions among climate, weathering, and erosion by bridging the gap between the palaeoclimatology and surface process communities by documenting the magnitude and distribution of climate change over tectonically active orogens.

Motivated by the need to better understand climate impacts on Earth surface processes, especially the denudation of orogens, we model palaeoclimate for four time slices in the late Cenozoic, use descriptive statistics to identify the extent of different regional climates, quantify changes in temperature and precipitation, and discuss the potential impacts on fluvial and/or hillslope erosion. In this study, we employ the ECHAM5 global atmospheric general circulation model (GCM) and document climate and climate change for time slices ranging between the Pliocene (PLIO, ∼ 3 Ma) to pre-industrial (PI) times for the St Elias Mountains of southeastern Alaska, the US Pacific Northwest (Olympic and Cascade ranges), western South America (Andes), and South Asia (including parts of central and East Asia). Our approach is twofold and includes

-

an empirical characterisation of palaeoclimates in these regions based on the covariance and spatial clustering of monthly precipitation and temperature, the monthly change in precipitation and temperature magnitude, and wind speeds where appropriate.

-

identification of changes in annual mean precipitation and temperature in selected regions for four time periods: (PLIO, Last Glacial Maximum (LGM), the mid-Holocene (MH), and PI) and subsequent validation of the simulated precipitation changes for the MH and LGM.

Our focus is on documenting climate and climate change in different locations with the intent of informing past and ongoing palaeodenudation studies of these regions. The results presented here also provide a means for future work to formulate testable hypotheses and investigations into whether or not regions of large palaeoclimate change produced a measurable signal in denudation rates or other Earth surface processes. More specifically, different aspects of the simulated palaeoclimate may be used as boundary conditions for vegetation and landscape evolution models, such as LPJ-GUESS and Landlab, to bridge the gap between climate change and quantitative estimates for Earth surface system responses. In this study, we intentionally refrain from applying predicted palaeoclimate changes to predict denudation rate changes. Such a prediction is beyond the scope of this study because a convincing (and meaningful) calculation of climate-driven transients in fluvial erosion (e.g. via the kinematic wave equation), variations in frost cracking intensity, or changes in hillslope sediment production and transport at the large regional scales considered here is not tractable within a single paper and instead is the focus of our ongoing work. Merited discussion of climatically induced changes in glacial erosion, as is important in the Cenozoic, is also beyond the scope of this study. Instead, our emphasis lies on providing and describing a consistently set-up GCM simulation framework for future investigations of Earth surface processes and identifying regions in which late Cenozoic climate changes potentially have a significant impact on fluvial and hillslope erosion.

2.1 ECHAM5 simulations

The global atmospheric GCM ECHAM5 (Roeckner et al., 2003) has been developed at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology and is based on the spectral weather forecast model of the ECMWF (Simmons et al., 1989). In the context of palaeoclimate applications, the model has been used mostly at lower resolution (T31, ca. 3.75∘ × 3.75∘; T63, ca. 1.9∘ × 1.9∘ in the case of Feng et al., 2016, and T106 in the case of Li et al., 2017 and Feng and Poulsen, 2016). The studies performed are not limited to the last millennium (e.g. Jungclaus et al., 2010) but also include research in the field of both warmer and colder climates, at orbital (e.g. Gong et al., 2013; Lohmann et al., 2013; Pfeiffer and Lohmann, 2016; X. Zhang et al., 2013, 2014; Wei and Lohmann, 2012) and tectonic timescales (e.g. Knorr et al., 2011; Stepanek and Lohmann, 2012), and under anthropogenic influence (Gierz et al., 2015).

Here, the ECHAM5 simulations were conducted at a T159 spatial resolution (horizontal grid size ca. 80 km × 80 km at the Equator) with 31 vertical levels (between the surface and 10 hPa). This high model resolution is admittedly not required for all of the climatological questions investigated in this study, and it should be noted that the skill of GCMs in predicting orographic precipitation remains limited at this scale (e.g. Meehl et al., 2007). However, simulations were conducted at this resolution so that future work can apply the results in combination with different dynamical and statistical downscaling methods to quantify changes at large catchment to orogen scales. The output frequency is relatively high (1 day) to enhance the usefulness of our simulations as input for landscape evolution and other models that may benefit from daily input. The simulations were conducted for five different time periods: present-day (PD), PI, MH, LGM, and PLIO.

A PD simulation (not shown here) was used to establish confidence in the model performance before conducting palaeosimulations and has been compared with the following observation-based datasets: European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF) reanalyses (ERA40, Uppala et al., 2005), National Centers for Environmental Prediction and National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCEP/NCAR) reanalyses (Kalnay et al., 1996; Kistler et al., 2001), NCEP Regional Reanalysis (NARR; Mesinger et al., 2006), the Climate Research Unit (CRU) TS3.21 dataset (Harris et al., 2013), High Asia Refined Analysis (HAR30; Maussion et al., 2014), and the University of Delaware dataset (UDEL v3.01; Legates and Wilmott, 1990). (See Mutz et al., 2016, for a detailed comparison with a lower-resolution model).

The PI climate simulation is an ECHAM5 experiment with PI (reference year 1850) boundary conditions. Sea surface temperatures (SSTs) and sea ice concentration (SIC) are derived from transient coupled ocean–atmosphere simulations (Lorenz and Lohmann, 2004; Dietrich et al., 2013). Following Dietrich et al. (2013), greenhouse gas (GHG) concentrations (CO2 : 280 ppm) are taken from ice-core-based reconstructions of CO2 (Etheridge et al., 1996), CH4 (Etheridge et al., 1998) and N2O (Sowers et al., 2003). Sea surface boundary conditions for the MH originate from a transient, low-resolution, coupled atmosphere–ocean simulation of the MH (6 ka) (Wei and Lohmann, 2012; Lohmann et al., 2013), where the GHG concentrations (CO2 : 280 ppm) are taken from ice core reconstructions of GHGs by Etheridge et al. (1996, 1998) and Sowers et al. (2003). GHG concentrations for the LGM (CO2 : 185 ppm) have been prescribed following Otto-Bliesner et al. (2006). Orbital parameters for the MH and LGM are set according to Dietrich et al. (2013) and Otto-Bliesner et al. (2006), respectively. LGM land–sea distribution and ice sheet extent and thickness are set based on the PMIP III (Palaeoclimate Modelling Intercomparison Project, phase 3) guidelines (elaborated on by Abe-Ouchi et al., 2015). Following Schäfer-Neth and Paul (2003), SST and SIC for the LGM are based on GLAMAP (Sarnthein et al., 2003) and CLIMAP (CLIMAP project members, 1981) reconstructions for the Atlantic Ocean and Pacific and Indian oceans, respectively. Global MH and LGM vegetation is based on maps of plant functional types by the BIOME 6000 Palaeovegetation Mapping Project (Prentice et al., 2000; Harrison et al., 2001; Bigelow et al., 2003; Pickett et al., 2004) and model predictions by Arnold et al. (2009). Boundary conditions for the PLIO simulation, including GHG concentrations (CO2 : 405), orbital parameters and surface conditions (SST, SIC, sea land mask, topography, and ice cover) are taken from the PRISM (Pliocene Research, Interpretation and Synoptic Mapping) project (Haywood et al., 2010; Sohl et al., 2009; Dowsett et al., 2010), specifically PRISM3D. The PLIO vegetation boundary condition was created by converting the PRISM vegetation reconstruction to the JSBACH plant functional types as described by Stepanek and Lohmann (2012), but the built-in land surface scheme was used.

SST reconstructions can be used as an interface between oceans and atmosphere (e.g. Li et al., 2017) instead of conducting the computationally more expensive fully coupled atmosphere–ocean GCM experiments. While the use of SST climatologies comes at the cost of capturing decadal-scale variability, and the results are ultimately biased towards the SST reconstructions the model is forced with; the simulated climate more quickly reaches an equilibrium state and the means of atmospheric variables used in this study do no change significantly after the relatively short spin-up period. The palaeoclimate simulations (PI, MH, LGM, PLIO) using ECHAM5 are therefore carried out for 17 model years, of which the first 2 years are used for model spinup. The monthly long-term averages (multi-year means for individual months) for precipitation, temperature, and precipitation and temperature amplitude, i.e. the mean difference between the hottest and coldest months, have been calculated from the following 15 model years for the analysis presented below.

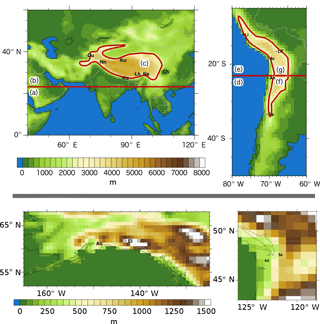

For further comparison between the simulations, the investigated regions were subdivided (Fig. 1). Western South America was subdivided into four regions: parts of tropical South America (80–60∘ W, 23.5–5∘ S); temperate South America (80–60∘ W, 50–23.5∘ S); tropical Andes (80–60∘ W, 23.5–5∘ S; high-pass filtered), i.e. most of the Peruvian Andes, Bolivian Andes, and northernmost Chilean Andes; and temperate Andes (80–60∘ W, 50–23.5∘ S, high-pass filtered). South Asia was subdivided into three regions: tropical South Asia (40–120∘ E, 0–23.5∘ N), temperate South Asia (40–120∘ E, 23.5–60∘ N), and high-altitude South Asia (40–120∘ E, 0–60∘ N; high-pass filtered).

Our approach of using a single GCM (ECHAM5) for our analysis is motivated by, and differs from, previous studies where inter-model variability exists from the use of different GCMs due to different parameterisations in each model. The variability in previous inter-model GCM comparisons exists despite the use of the same forcings (e.g. see results highlighted in IPCC AR5). Similarities identified between these palaeoclimate simulations conducted with different GCMs using similar boundary conditions can establish confidence in the models when in agreement with proxy reconstructions. However, differences identified in inter-model GCM comparisons highlight biases by all or specific GCMs, or reveal sensitivities to one changed parameter, such as model resolution. Given these limitations of GCM modelling, we present in this study a comparison of a suite of ECHAM5 simulations to proxy-based reconstructions (where possible) and, to a lesser degree, comment on general agreement or disagreement of our ECHAM5 results with other modelling studies. A detailed inter-model comparison of our results with other GCMs is beyond the scope of this study and better suited for a different study in a journal with a different focus and audience. Rather, by using the same GCM and identical resolution for the time slice experiments, we reduce the number of parameters (or model parameterisations) varying between simulations and thereby remove potential sources of error or uncertainty that would otherwise have to be considered when comparing output from different models with different parameterisations of processes, model resolution, and in some cases model forcings (boundary conditions). Nevertheless, the reader is advised to use these model results with the GCM's shortcoming and uncertainties in boundary condition reconstructions in mind. For example, precipitation results may require dynamical or statistical downscaling to increase accuracy where higher-resolution precipitation fields are required. Furthermore, readers are advised to familiarise themselves with the palaeogeography reconstruction initiatives and associated uncertainties. For example, while Pliocene ice sheet volume can be estimated, big uncertainties pertaining to their locations remain (Haywood et al., 2010).

2.2 Cluster analysis to document temporal and spatial changes in climatology

The aim of the clustering approach is to group climate model surface grid boxes together based on similarities in climate. Cluster analyses are statistical tools that allow elements (i) to be grouped by similarities in the elements' attributes. In this study, those elements are spatial units, the elements' attributes are values from different climatic variables, and the measure of similarity is given by a statistical distance. The four basic variables used as climatic attributes of these spatial elements are near-surface (2 m) air temperature, seasonal 2 m air temperature amplitude, precipitation rate, and seasonal precipitation rate amplitude. Since monsoonal winds are a dominant feature of the climate in the South Asia region, near-surface (10 m) speeds of u wind and v wind (zonal and meridional wind components, respectively) during the monsoon season (July) and outside the monsoon season (January) are included as additional variables in our analysis of that region. Similarly, u-wind and v-wind speeds during (January) and outside (July) the monsoon season in South America are added to the list of considered variables to take into account the South American Monsoon System (SASM) in the cluster analysis for this region. The long-term monthly means of those variables are used in a hierarchical clustering method, followed by a non-hierarchical k-means correction with randomised regroupment (Mutz et al., 2016; Wilks, 2011; Paeth, 2004; Bahrenberg et al., 1992).

The hierarchical part of the clustering procedure starts with as many clusters as there are elements (ni), then iteratively combines the most similar clusters to form a new cluster using centroids for the linkage procedure for clusters containing multiple elements. The procedure is continued until the desired number of clusters (k) is reached. One disadvantage of a pure hierarchical approach is that elements cannot be recategorised once they are assigned to a cluster, even though the addition of new elements to existing clusters changes the clusters' defining attributes and could warrant a recategorisation of elements. We address this problem by implementation of a (non-hierarchical) k-means clustering correction (e.g. Paeth, 2004). Elements are recategorised based on the multivariate centroids determined by the hierarchical cluster analysis in order to minimise the sum of deviations from the cluster centroids. The Mahalanobis distance (e.g. Wilks, 2011) is used as a measure of similarity or distance between the cluster centroids since it is a statistical distance and thus not sensitive to different variable units. The Mahalanobis distance also accounts for possible multi-collinearity between variables.

The end results of the cluster analyses are subdivisions of the climate in the investigated regions into k subdomains or clusters based on multiple climate variables. The region-specific k has to be prescribed before the analyses. A large k may result in redundant additional clusters describing very similar climates, thereby defeating the purpose of the analysis to identify and describe the dominant, distinctly different climates in the region and their geographical coverage. Since it is not possible to know a priori the ideal number of clusters, k was varied between 3 and 10 for each region and the results presented below identify the optimal number of visibly distinctly different clusters from the analysis. Optimal k was determined by assessing the distinctiveness and similarities between the climate clusters in the systematic process of increasing k from 3 to 10. Once an increase in k no longer resulted in the addition of another cluster that was climatologically distinctly different from the others, and instead resulted in at least two similar clusters, k of the previous iteration was chosen as the optimal k for the region.

The cluster analysis ultimately results in a description of the geographical extent of a climate (cluster) characterised by a certain combination of mean values for each of the variables associated with the climate. For example, climate cluster 1 may be the most tropical climate in a region and thus be characterised by high precipitation values, high temperature values, and low seasonal temperature amplitude. Each of the results (consisting of the geographical extent of climates and mean vectors describing the climate) can be viewed as an optimal classification for the specific region and time. It serves primarily as a means for providing an overview of the climate in each of the regions at different times, reduces dimensionality of the raw simulation output, and identifies regions of climatic homogeneity that are difficult to notice by viewing simple maps of each climate variable. Its synoptic purpose is similar to that of the widely known Köppen–Geiger classification scheme (Peel et al., 2007), but we allow for optimal classification rather than prescribe classes, and our selection of variables is more restricted and made in accordance with the focus of this study.

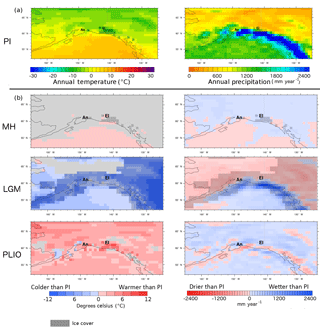

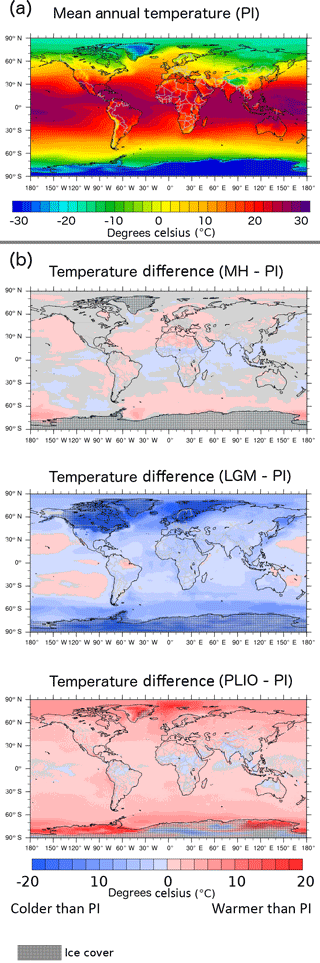

Results from our analysis are first presented for general changes in global temperature and precipitation for the different time slices (Figs. 2, 3), which is then followed by an analysis of changes in the climatology of selected orogens. A more detailed description of temperature and precipitation changes in our selected orogens is presented in subsequent subsections (Fig. 4 and following). All differences in climatology are expressed relative to the PI control run. Changes relative to the PI rather than PD conditions are presented to avoid interpreting an anthropogenic bias in the results and focusing instead on pre-anthropogenic variations in climate. For brevity, near-surface (2 m) air temperature and total precipitation rate are referred to as temperature and precipitation.

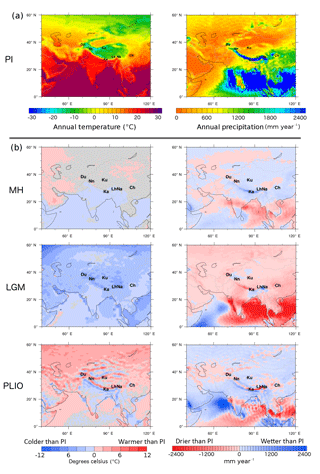

3.1 Global differences in mean annual temperature

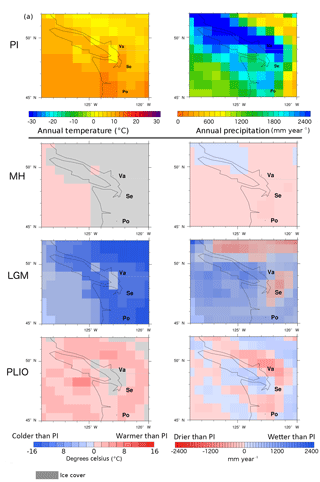

This section describes the differences between simulated MH, LGM, and PLIO annual mean temperature anomalies with respect to PI shown in Fig. 2b, and PI temperature absolute values shown in Fig. 2a. Most temperature differences between the PI and MH climate are within −1 to 1 ∘C. Exceptions to this are the Hudson Bay, Weddell Sea, and Ross Sea regions, which experience warming of 1–3, 1–5, and 1–9 ∘C, respectively. Continental warming is mostly restricted to low-altitude South America, Finland, western Russia, the Arabian peninsula (1–3 ∘C), and subtropical North Africa (1–5 ∘C). Simulation results show that LGM and PLIO annual mean temperature deviate from the PI means the most. The global PLIO warming and LGM cooling trends are mostly uniform in direction, but the magnitude varies regionally. The strongest LGM cooling is concentrated in regions where the greatest change in ice extent occurs (as indicated in Fig. 2), i.e. Canada, Greenland, the North Atlantic, northern Europe, and Antarctica. Central Alaska shows no temperature changes, whereas coastal southern Alaska experiences cooling of ≤ 9 ∘C. Cooling in the US Pacific Northwest is uniform and between 11 and 13 ∘C. Most of high-altitude South America experiences mild cooling of 1–3 ∘C, 3–5 ∘C in the central Andes, and ≤ 9 ∘C in the south. Along the Himalayan orogen, LGM temperature values are 5–7 ∘C below PI values. Much of central Asia and the Tibetan Plateau cools by 3–5 ∘C, and most of India, low-altitude China, and South East Asia cools by 1–3 ∘C.

Figure 2Global PI annual mean near-surface temperatures (a) and deviations of MH, LGM, and PLIO annual mean near-surface temperatures from PI values (b). Units are ∘C and insignificant (p < 99 %) differences (as determined by a t test) are greyed out.

In the PLIO climate, parts of Antarctica, Greenland, and the Greenland Sea experience the greatest temperature increase (≤ 19 ∘C). Most of southern Alaska warms by 1–5 and ≤ 9 ∘C near McCarthy, Alaska. The US Pacific Northwest warms by 1–5 ∘C. The strongest warming in South America is concentrated at the Pacific west coast and the Andes (1–9 ∘C), specifically between Lima and Chiclayo, and along the Chilean–Argentinian Andes south of Bolivia (≤ 9 ∘C). Parts of low-altitude South America to the immediate east of the Andes experience cooling of 1–5 ∘C. The Himalayan orogen warms by 3–9 ∘C, whereas Myanmar, Bangladesh, Nepal, northern India, and northeastern Pakistan cool by 1–9 ∘C.

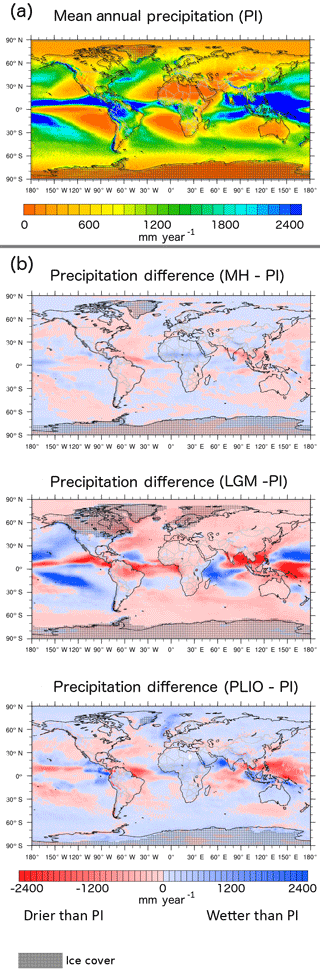

3.2 Global differences in mean annual precipitation

Notable differences occur between simulated MH, LGM, and PLIO annual mean precipitation anomalies with respect to PI shown in Fig. 3b and the PI precipitation absolute values shown in Fig. 3a. Of these, MH precipitation deviates the least from PI values. The differences between MH and PI precipitation on land appear to be largest in northern tropical Africa (increase ≤ 1200 mm a−1), along the Himalayan orogen (increase ≤ 2000 mm a−1), and in central Indian states (decrease) ≤ 500 mm. The biggest differences in western South America are precipitation increases in central Chile between Santiago and Puerto Montt. The LGM climate shows the largest deviation in annual precipitation from the PI climate, and precipitation on land mostly decreases. Exceptions are increases in precipitation rates in North American coastal regions, especially in coastal southern Alaska (≤ 2300 mm a−1) and the US Pacific Northwest (≤ 1700 mm a−1). Further exceptions are precipitation increases in low-altitude regions immediately east of the Peruvian Andes (≤ 1800 mm a−1), central Bolivia (≤ 1000 mm a−1), most of Chile (≤ 1000 mm a−1), and northeastern India (≤ 1900 mm a−1). Regions of notable precipitation decrease are northern Brazil (≤ 1700 mm a−1), southernmost Chile and Argentina (≤1900 mm a−1), coastal south Peru (≤ 700 mm a−1), central India (≤ 2300 mm a−1), and Nepal (≤ 1600 mm a−1).

Figure 3Global PI annual mean precipitation (a) and deviations of MH, LGM, and PLIO annual mean near-surface temperatures from PI values (b). Units are millimetres per year.

Most of the precipitation on land in the PLIO climate is higher than that in the PI climate. Precipitation is enhanced by ca. 100–200 mm a−1 in most of the Atacama Desert, by ≤ 1700 mm a−1 south of the Himalayan orogen, and by ≤ 1400 mm a−1 in tropical South America. Precipitation significantly decreases in central Peru (≤ 2600 mm), southernmost Chile (≤ 2600 mm), and from eastern Nepal to northernmost northeastern India (≤ 250 0mm).

3.3 Palaeoclimate characterisation from the cluster analysis and changes in regional climatology

In addition to the global changes described above, the PLIO to PI regional climatology changes substantially in the four investigated regions of South Asia (Sect. 3.3.1), the Andes (Sect. 3.3.2), southern Alaska (Sect. 3.3.3), and the Cascade Range (Sect. 3.3.4). Each climate cluster defines a separate distinct climate that is characterised by the mean values of the different climate variables used in the analysis. The clusters are calculated by taking the arithmetic means of all the values (climatic means) calculated for the grid boxes within each region. The regional climates are referred to by their cluster number C1, C2, …, Ck, where k is the number of clusters specified for the region. The clusters for specific palaeoclimates are mentioned in the text as Ci[t], where i corresponds to the cluster number (i= 1, …, k) and t to the simulation time period (t= PI, MH, LGM, PLIO). The descriptions first highlight the similarities and then the differences in regional climate. The cluster means of seasonal near-surface temperature amplitude and seasonal precipitation amplitude are referred to as temperature and precipitation amplitude. The median, 25th percentile, 75th percentile, minimum, and maximum values for annual mean precipitation are referred to as Pmd, P25, P75, Pmin, and Pmax, respectively. Likewise, the same statistics for temperature are referred to as Tmd, T25, T75, Tmin, and Tmax. These are presented as box plots of climate variables in different time periods. When the character of a climate cluster is described as “high”, “moderate”, and “low”, the climatic attribute's values are described relative to the value range of the specific region in time; thus high PLIO precipitation rates may be higher than high LGM precipitation rates. The character is presented in a raster plot to allow compact visual representation of it. The actual mean values for each variable in every time slice and region-specific cluster are included in tables in the Supplement.

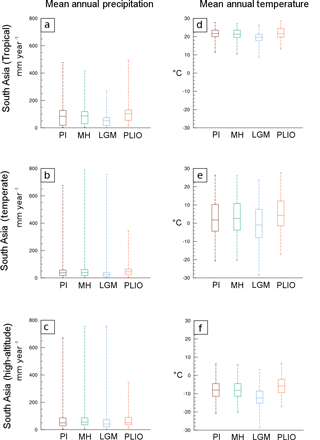

Figure 4PI annual mean near-surface temperatures (a) and deviations of MH, LGM, and PLIO annual mean near-surface temperatures from PI values (b) for the South Asia region. Insignificant (p < 99 %) differences (as determined by a t test) are greyed out.

3.3.1 Climate change and palaeoclimate characterisation in South, central, and East Asia

This section describes the regional climatology of the four investigated Cenozoic time slices and how precipitation and temperature changes from PLIO to PI times in tropical, temperate, and high-altitude regions. LGM and PLIO simulations show the largest simulated temperature and precipitation deviations (Fig. 4b) from PI temperature and precipitation (Fig. 4a) in the South Asia region. LGM temperatures are 1–7 ∘C below PI temperatures and the direction of deviation is uniform across the study region. PLIO temperature is mostly above PI temperatures by 1–7 ∘C. The cooling of 3–5 ∘C in the region immediately south of the Himalayan orogen represents one of the few exceptions. Deviations of MH precipitation from PI precipitation in the region are greatest along the eastern Himalayan orogeny, which experiences an increase in precipitation (≤ 2000 mm a−1). The same region experiences a notable decrease in precipitation in the LGM simulation, which is consistent in direction with the prevailing precipitation trend on land during the LGM. PLIO precipitation on land is typically higher than PI precipitation.

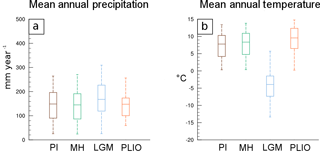

Annual means of precipitation and temperature spatially averaged for the regional subdivisions and the different time slice simulations have been compared. The value range P25 to P75 of precipitation is higher for tropical South Asia than for temperate and high-altitude South Asia (Fig. 5a–c). The LGM values for P25, Pmd, and P75 are lower than for the other time slice simulations, most visibly for tropical South Asia (ca. 100 mm a−1). The temperature range (both T75–T25 and Tmax–Tmin) is smallest in hot (ca. 21 ∘C) tropical South Asia, wider in high-altitude (ca. −8 ∘C) South Asia, and widest in temperate (ca. 2 ∘C) South Asia (Fig. 5d–f). Tmd, T25, and T75 values for the LGM are ca. 1 ∘C, 1–2, and 2 ∘C below PI and MH temperatures in tropical, temperate, and high-altitude South Asia, respectively, whereas the same temperature statistics for the PLIO simulation are ca. 1 ∘C above PI and MH values in all regional subdivisions (Fig. 5d–f). With respect to PI and MH values, precipitation and temperature are generally lower in the LGM and higher in the PLIO in tropical, temperate, and high-altitude South Asia.

Figure 5PI, MH, LGM, and PLIO annual mean precipitation in (a) tropical South Asia, (b) temperate South Asia, and (c) high-altitude South Asia; PI, MH, LGM, and PLIO annual mean temperatures in (d) tropical South Asia, (e) temperate South Asia, and (f) high-altitude South Asia. For each time slice, the minimum, lower 25th percentile, median, upper 75th percentile, and maximum are plotted.

Figure 6Geographical coverage and characterisation of climate classes C1–C6 based on cluster analysis of eight variables (near-surface temperature, seasonal near-surface temperature amplitude, total precipitation, seasonal precipitation amplitude, u wind in January and July, v wind in January and July) in the South Asia region. The geographical coverage of the climates C1–C6 is shown on the left for the PI (a), MH (b), LGM (c), and PLIO (d); the complementary, time-slice-specific characterisation of C1–C6 for the PI (e), MH (f), LGM (g), and PLIO (h) is shown on the right.

In all time periods, the wettest climate cluster C1 covers an area along the southeastern Himalayan orogen (Fig. 6a–d) and is defined by the highest precipitation amplitude (dark blue, Fig. 6e–h). C5(PI), C3(MH), C4(LGM), and C5(PLIO) are characterised by (dark blue, Fig. 6e–h) the highest temperatures and u-wind and v-wind speeds during the summer monsoon in their respective time periods, whereas C4(PI), C5(MH), and C6(LGM) are defined by low temperatures and the highest temperature amplitude and u-wind and v-wind speeds outside the monsoon season (in January) in their respective time periods (Fig. 6e–h). The latter three climate classes cover much of the more continental, northern landmass in their respective time periods and represent a cooler climate affected more by seasonal temperature fluctuations (Fig. 6a–d). The two wettest climate clusters C1 and C2 are more restricted to the eastern end of the Himalayan orogen in the LGM than during other times, indicating that the LGM precipitation distribution over the South Asia landmass is more concentrated in this region than in other time slice experiments.

3.3.2 Climate change and palaeoclimate characterisation in the Andes, western South America

This section describes the cluster-analysis-based regional climatology of the four investigated late Cenozoic time slices and illustrates how precipitation and temperature changes from PLIO to PI in tropical and temperate low- and high-altitude (i.e. Andes) regions in western South America (Figs. 7–9).

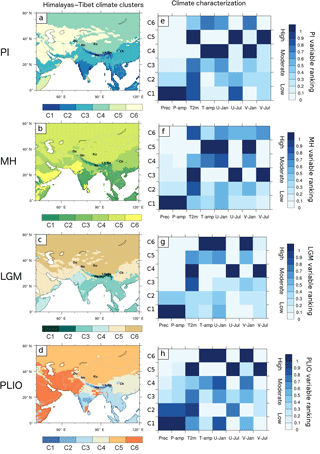

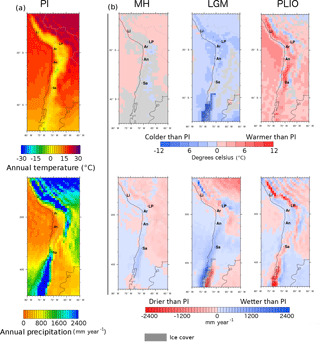

Figure 7PI annual mean near-surface temperatures (a) and deviations of MH, LGM, and PLIO annual mean near-surface temperatures from PI values (b) for western South America. Insignificant (p < 99 %) differences (as determined by a t test) are greyed out.

LGM and PLIO simulations show the largest simulated deviations (Fig. 7b) from PI temperature and precipitation (Fig. 7a) in western South America. The direction of LGM temperature deviations from PI temperatures is negative and uniform across the region. LGM temperatures are typically 1–3 ∘C below PI temperatures across the region and 1–7 ∘C below PI values in the Peruvian Andes, which also experience the strongest and most widespread increase in precipitation during the LGM (≤ 1800 mm a−1). Other regions, such as much of the northern Andes and tropical South America, experience a decrease in precipitation in the same experiment. PLIO temperature is mostly elevated above PI temperatures by 1–5 ∘C. The Peruvian Andes experience a decrease in precipitation (≤ 2600 mm), while the northern Andes are wetter in the PLIO simulation compared to the PI control simulation.

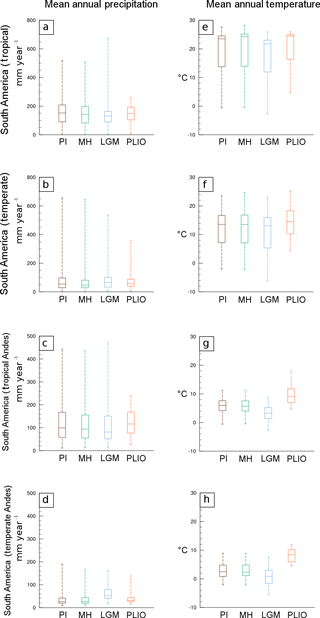

PI, MH, LGM, and PLIO precipitation and temperature means for regional subdivisions have been compared. The P25 to P75 range is smallest for the relatively dry temperate Andes and largest for tropical South America and the tropical Andes (Fig. 8a–d). Pmax is lowest in the PLIO in all four regional subdivisions even though Pmd, P25, and P75 in the PLIO simulation are similar to the same statistics calculated for PI and MH time slices. Pmd, P25, and P75 for the LGM are ca. 50 mm a−1 lower in tropical South America and ca. 50 mm a−1 higher in the temperate Andes. Average PLIO temperatures are slightly warmer and LGM temperatures are slightly colder than PI and MH temperatures in tropical and temperate South America (Fig. 8e and f). These differences are more pronounced in the Andes, however. Tmd, T25, and T75 are ca. 5 ∘C higher in the PLIO climate than in PI and MH climates in both the temperate and tropical Andes, whereas the same temperatures for the LGM are ca. 2–4 ∘C below PI and MH values (Fig. 8g and h).

Figure 8PI, MH, LGM, and PLIO annual mean precipitation in (a) tropical South America, (b) temperate South America, (c) the tropical Andes, and (d) the temperate Andes; PI, MH, LGM, and PLIO annual mean temperatures in (e) tropical South America, (f) temperate South America, (g) the tropical Andes, and (h) the temperate Andes. For each time slice, the minimum, lower 25th percentile, median, upper 75th percentile, and maximum are plotted.

For the LGM, the model computes drier-than-PI conditions in tropical South America and the tropical Andes, enhanced precipitation in the temperate Andes, and a decrease in temperature that is most pronounced in the Andes. For the PLIO, the model predicts precipitation similar to PI, but with lower precipitation maxima. PLIO temperatures generally increase from PI temperatures, and this increase is most pronounced in the Andes.

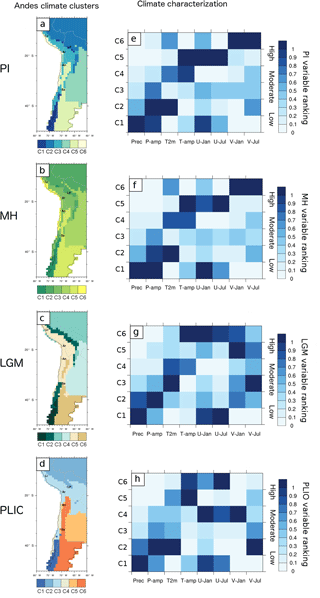

Figure 9Geographical coverage and characterisation of climate classes C1–C6 based on cluster analysis of eight variables (near-surface temperature, seasonal near-surface temperature amplitude, precipitation, seasonal precipitation amplitude, u wind in January and July, v wind in January and July) in western South America. The geographical coverage of the climates C1–C6 is shown on the left for PI (a), MH (b), LGM (c), and PLIO (d); the complementary, time-slice-specific characterisation of C1–C6 for PI (e), MH (f), LGM (g), and PLIO (h) is shown on the right.

The climate variability in the region is described by six different clusters (Fig. 9a–d), which have similar attributes in all time periods. The wettest climate C1 is also defined by moderate to high precipitation amplitudes, low temperatures, and moderate to high u-wind speeds in summer and winter in all time periods (dark blue, Fig. 9e–h). C2(PI), C2(MH), C3(LGM), and C2(PLIO) are characterised by high temperatures and low seasonal temperature amplitude (dark blue, Fig. 9e–h), geographically cover the north of the investigated region, and represent a more tropical climate. C5(PI), C5(MH), C6(LGM), and C6(PLIO) are defined by low precipitation and precipitation amplitude, high temperature amplitude, and high u-wind speeds in winter (Fig. 9e–h), cover the low-altitude south of the investigated region (Fig. 9a–d), and represent dry, extratropical climates with more pronounced seasonality. In the PLIO simulation, the lower-altitude east of the region has four distinct climates, whereas the analysis for the other time slice experiments only yield three distinct climates for the same region.

3.3.3 Climate change and palaeoclimate characterisation in the St Elias Mountains, southeastern Alaska

This section describes the changes in climate and the results from the cluster analysis for southern Alaska (Figs. 10–12). As is the case for the other study areas, LGM and PLIO simulations show the largest simulated deviations (Fig. 10b) from PI temperature and precipitation (Fig. 10a). The sign of LGM temperature deviations from PI temperatures is negative and uniform across the region. LGM temperatures are typically 1–9 ∘C below PI temperatures, with the east of the study area experiencing the largest cooling. PLIO temperatures are typically 1–5 ∘C above PI temperatures and the warming is uniform for the region. In comparison to the PI simulation, LGM precipitation is lower on land but higher (≤ 2300 mm) in much of the coastal regions of southern Alaska. Annual PLIO precipitation is mostly higher (≤ 800 mm) than for PI.

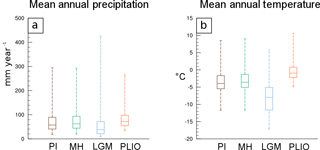

Pmd, P25, P75, Pmin, and Pmax for southern Alaskan mean annual precipitation do not differ much between PI, MH, and PLIO climates, while Pmd, P25, P75, and Pmin decrease by ca. 20–40 mm a−1 and Pmax increases during the LGM (Fig. 11a). The Alaskan PLIO climate is distinguished from the PI and MH climates by its higher (ca. 2 ∘C) regional temperature means, T25, T75, and Tmd (Fig. 11b). Mean annual temperatures, T25, T75, Tmin, and Tmax, are lower in the LGM than in any other considered time period (Fig. 11b), and about 3–5 ∘C lower than during the PI and MH.

Figure 11PI, MH, LGM, and PLIO annual mean precipitation (a) and mean annual temperatures (b) in southern Alaska. For each time slice, the minimum, lower 25th percentile, median, upper 75th percentile, and maximum are plotted.

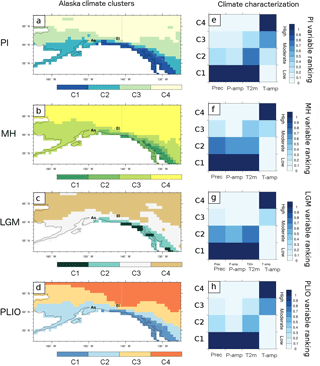

Distinct climates are present in the PLIO to PI simulations for southeastern Alaska. Climate cluster C1 is always geographically restricted to coastal southeastern Alaska (Fig. 12a–d) and characterised by the highest precipitation, precipitation amplitude, and temperature and by relatively low temperature amplitude (dark blue, Fig. 12e–h). Climate C2 is characterised by moderate to low precipitation, precipitation amplitude, and temperature and by low temperature amplitude. C2 is either restricted to coastal southeastern Alaska (in MH and LGM climates) or coastal southern Alaska (in PI and PLIO climates). Climate C3 is described by low precipitation, precipitation amplitude, and temperature and moderate temperature amplitude in all simulations. It covers coastal western Alaska and separates climate C1 and C2 from the northern C4 climate. Climate C4 is distinguished by the highest mean temperature amplitude, by low temperature and precipitation amplitude, and by the lowest precipitation.

The geographical ranges of PI climates C1–C4 and PLIO climates C1–C4 are similar. C1(PI∕PLIO) and C2(PI∕PLIO) spread over a larger area than C1(MH∕LGM) and C2(MH∕LGM). C2(PI∕PLIO) are not restricted to coastal southeastern Alaska, but also cover the coastal southwest of Alaska. The main difference in characterisation between PI and PLIO climates C1–C4 lies in the greater difference (towards lower values) in precipitation, precipitation amplitude, and temperature from C1(PLIO) to C2(PLIO) compared to the relatively moderate decrease in those means from C1(PI) to C2(PI).

Figure 12Geographical coverage of climate classes C1–C4 based on cluster analysis of four variables (near-surface temperature, seasonal near-surface temperature amplitude, total precipitation, seasonal total precipitation amplitude) in southern Alaska. The geographical coverage of the climates C1–C4 is shown on the left for PI (a), MH (b), LGM (c), and PLIO (d); the complementary, time-slice-specific characterisation of C1–C6 for PI (e), MH (f), LGM (g), and PLIO (h) is shown on the right.

3.3.4 Climate change and palaeoclimate characterisation in the Cascade Range, US Pacific Northwest

Figure 13PI annual mean near-surface temperatures (a) and deviations of MH, LGM, and PLIO annual mean near-surface temperatures from PI values (b) for the US Pacific Northwest. Insignificant (p < 99 %) differences (as determined by a t test) are greyed out.

This section describes the character of regional climatology in the US Pacific Northwest and its change over time (Figs. 13–15). The region experiences cooling of typically 9–11 ∘C on land during the LGM and warming of 1–5 ∘C during the PLIO (Fig. 13b) when compared to PI temperatures (Fig. 13a). LGM precipitation increases over water, decreases on land by ≤ 800 mm a−1 in the north and in the vicinity of Seattle, and increases on land by ≤ 1400 mm a−1 on Vancouver Island and around Portland and the Olympic Mountains. Conversely, PLIO precipitation does not deviate much from PI values over water and varies in the direction of deviation on land. MH temperature and precipitation deviation from PI values is negligible.

Pmd, P25, P75, Pmin, and Pmax for the Cascade Range do not notably differ between the four time periods (Fig. 14a). The LGM range of precipitation values is slightly larger than that of the PI and MH with slightly increased Pmd, while the respective range is smaller for simulation of the PLIO. The Tmd, T25, T75, and Tmax values for the PLIO climate are ca. 2 ∘C higher than those values for PI and MH (Fig. 14b). All temperature statistics for the LGM are notably (ca. 13 ∘C) below their analogues in the other time periods (Fig. 14b).

PI, LGM, and PLIO clusters are similar in both their geographical patterns (Fig. 15a, c, d) and their characterisation by mean values (Fig. 15e, g, h). C1 is the wettest cluster and shows the highest amplitude in precipitation. The common characteristics of the C2 cluster are moderate to high precipitation and precipitation amplitude. C4 is characterised by the lowest precipitation and precipitation amplitudes and the highest temperature amplitudes. Regions assigned to clusters C1 and C2 are in proximity to the coast, whereas C4 is geographically restricted to more continental settings.

Figure 14PI, MH, LGM, and PLIO annual mean precipitation (a) and annual mean temperatures (b) in the Cascades, US Pacific Northwest. For each time slice, the minimum, lower 25th percentile, median, upper 75th percentile, and maximum are plotted.

Figure 15Geographical coverage and characterisation of climate classes C1–C4 based on cluster analysis of four variables (near-surface temperature, seasonal near-surface temperature amplitude, total precipitation, seasonal total precipitation amplitude) in the Cascades, US Pacific Northwest. The geographical coverage of the climates C1–C4 is shown on the left for PI (a), MH (b), LGM (c), and PLIO (d); the complementary, time-slice-specific characterisation of C1–C6 for PI (e), MH (f), LGM (g), and PLIO (h) is shown on the right.

In the PI and LGM climates, the wettest cluster C1 is also characterised by high temperatures (Fig. 10e, g). However, virtually no grid boxes were assigned to C1(LGM). C1(MH) differs from other climate states' C1 clusters in that it is also described by moderate to high near-surface temperature and temperature amplitude (Fig. 10f), and in that it is geographically less restricted and covers much of Vancouver Island and the continental coastline north of it (Fig. 10b). Near-surface temperatures are highest for C2 in PI, LGM, and PLIO climates (Fig. 10e, g, h) and low for C2(MH) (Fig. 10f). C2(MH) is also geographically more restricted than C2 clusters in PI, LGM, and PLIO climates (Fig. 10a–d). C2(PI), C2(MH), and C2(LGM) have a low temperature amplitude (Fig. 10e–g), whereas C2(PLIO) is characterised by a moderate temperature amplitude (Fig. 10h).

In the following, we synthesise our results and compare to previous studies that investigate the effects of temperature and precipitation change on erosion. Since our results do not warrant merited discussion of subglacial processes without additional work that is beyond the scope of this study, we instead advise caution in interpreting the presented precipitation and temperature results in an erosional context in which the regions are covered with ice. For convenience, ice cover is indicated in Figs. 2, 3, 7, 10 and 13, and a summary of ice cover used as boundary conditions for the different time slice experiments is included in the Supplement. Where possible, we relate the magnitude of climate change predicted in each geographical study area with terrestrial proxy data.

4.1 Synthesis of temperature changes

4.1.1 Temperature changes and implications for weathering and erosion

Changes in temperature can affect physical weathering due to temperature-induced changes in periglacial processes and promote frost cracking, frost creep (e.g. Matsuoka, 2001; Schaller et al., 2002; Matsuoka and Murton, 2008; Delunel et al., 2010; Andersen et al., 2015; Marshall et al., 2015), and biotic weathering and erosion (e.g. Moulton and Berner, 1998; Banfield et al., 1999; Dietrich and Perron, 2006). Quantifying and understanding past changes in temperature is thus vital for our understanding of denudation histories. In the following, we highlight regions in the world where future observational studies might be able to document significant warming or cooling that would influence temperature-related changes in physical and chemical weathering over the last ∼ 3 Myr.

Simulated MH temperatures show little deviation (typically < 1 ∘C) from PI temperatures in the investigated regions (Fig. 2b), suggesting little difference in MH temperature-related weathering. The LGM experiences widespread cooling, which is accentuated at the poles, increasing the Equator-to-pole pressure gradient and consequently strengthening global atmospheric circulation. Despite this global trend, cooling in coastal southern Alaska is higher (≤ 9 ∘C) than in central Alaska (0 ± 1 ∘C). The larger temperature difference in southern Alaska geographically coincides with ice cover (Fig. 10b) and should thus be interpreted in the context of a different erosional regime. Cooling in most of the lower-latitude regions in South America and central to South East Asia is relatively mild. The greatest temperature differences in South America are observed for western Patagonia, which was mostly covered by glaciers. The Tibetan Plateau experiences more cooling (3–5 ∘C) than adjacent low-altitude regions (1–3 ∘C) during the LGM.

The PLIO simulation is generally warmer, and temperature differences accentuate warming at the poles. Warming in simulation PLIO is greatest in parts of Canada, Greenland, and Antarctica (up to 19 ∘C), which geographically coincides with the presence of ice in the PI reference simulation and thus may be attributed to differences in ice cover. It should therefore also be regarded as areas in which process domain shifted from glacial to non-glacial. The warming in simulation PLIO in southern Alaska and the US Pacific Northwest is mostly uniform and in the range of 1–5 ∘C. As before, changes in ice cover reveal that the greatest warming may be associated with the absence of glaciers relative to the PI simulation. Warming in South America is concentrated at the Pacific west coast and the Andes between Lima and Chiclayo and along the Chilean–Argentinian Andes south of Bolivia (≤ 9 ∘C).

Overall, annual mean temperatures in the MH simulation show little deviation from PI values. The more significant temperature deviations of the colder LGM and of the warmer PLIO simulations are accentuated at the poles, leading to higher and lower Equator-to-pole temperature gradients, respectively. The largest temperature-related changes (relative to PI conditions) in weathering and subsequent erosion, in many cases through a shift in the process domain from glacial to non-glacial or vice versa, are therefore to be expected in the LGM and PLIO climates.

4.1.2 Temperature comparison to other studies

LGM cooling is accentuated at the poles, thus increasing the Equator-to-pole pressure gradient and consequently strengthens global atmospheric circulation, and is in general agreement with studies such as Otto-Bliesner et al. (2006) and Braconnot et al. (2007). The PLIO simulation shows little to no warming in the tropics and accentuated warming at the poles, as do findings of Salzmann et al. (2011), Robinson (2009), and Ballantyne (2010), respectively. This would reduce the Equator-to-pole sea and land surface temperature gradient, as also reported by Dowsett et al. (2010), and also weaken global atmospheric circulation. Agreement with proxy-based reconstructions, as is the case of the relatively little warming in lower latitudes, is not surprising given that SST reconstructions (derived from previous coarse resolution coupled ocean–atmosphere models) are prescribed in this uncoupled atmosphere simulation. It should be noted that coupled ocean–atmosphere simulations do predict more low-latitude warming (e.g. Stepanek and Lohmann, 2012; R. Zhang et al., 2013). The PLIO warming in parts of Canada and Greenland (up to 19 ∘C) is consistent with values based on multi-proxy studies (Ballantyne et al., 2010). Due to a scarcity of palaeobotanical proxies in Antarctica, reconstruction-based temperature and ice sheet extent estimates for a PLIO climate have high uncertainties (Salzmann et al., 2011), making model validation difficult. Furthermore, controversy about relatively little warming in the south polar regions compared to the north polar regions remains (e.g. Hillenbrand and Fütterer, 2002; Wilson et al., 2002). Mid-latitude PLIO warming is mostly in the 1–3 ∘C range with notable exceptions of cooling in the northern tropics of Africa and on the Indian subcontinent, especially south of the Himalayan orogen.

4.2 Synthesis of precipitation changes

4.2.1 Precipitation and implications for weathering and erosion

Changes in precipitation affects erosion through river incision, sediment transport, and erosion due to extreme precipitation events and storms (e.g. Whipple and Tucker, 1999; Hobley et al., 2010). Furthermore, vegetation type and cover also co-evolve with variations in precipitation and with changes in geomorphology (e.g. Marston, 2010; Roering et al., 2010). These vegetation changes in turn modify hillslope erosion by increasing root mass and canopy cover and decreasing water-induced erosion via surface run-off (e.g. Gyssels et al., 2005). Therefore, understanding and quantifying changes in precipitation in different palaeoclimates is necessary for a more complete reconstruction of orogen denudation histories. A synthesis of predicted precipitation changes is provided below and highlights regions where changes in river discharge and hillslope processes might be impacted by climate change over the last ∼ 3 Myr.

Most of North Africa is notably wetter during the MH, which is characteristic of the African Humid Period (Sarnthein, 1978). This pluvial regional expression of the Holocene Climatic Optimum is attributed to sudden changes in the strength of the African monsoon caused by orbital-induced changes in summer insolation (e.g. deMenocal et al., 2000). Southern Africa is characterised by a wetter climate to the east and drier climate to the west of the approximate location of the Congo Air Boundary (CAB), the migration of which has previously been cited as a cause for precipitation changes in East Africa (e.g. Juninger et al., 2014). In contrast, simulated MH precipitation rates show little deviation from the PI in most of the investigated regions, suggesting little difference in MH precipitation-related erosion. The Himalayan orogen is an exception and shows a precipitation increase of up to 2000 mm a−1. The climate's enhanced erosion potential, which could result from such a climatic change, should be taken into consideration when palaeoerosion rates estimated from the geological record in this area are interpreted (e.g. Bookhagen et al., 2005). Specifically, higher precipitation rates (along with differences in other rainfall-event parameters) could increase the probability of mass movement events on hillslopes, especially where hillslopes are close to the angle of failure (e.g. Montgomery, 2001), and modify fluxes to increase shear stresses exerted on river beds and increase stream capacity to enhance erosion on river beds (e.g. by abrasion).

Most precipitation on land is decreased during the LGM due to large-scale cooling and decreased evaporation over the tropics, resulting in an overall decrease in inland moisture transport (e.g. Braconnot et al., 2007). North America, south of the continental ice sheets, is an exception and experiences increases in precipitation. For example, the investigated US Pacific Northwest and the southeastern coast of Alaska experience strongly enhanced precipitation of ≤ 1700 and ≤ 2300 mm a−1, respectively. These changes geographically coincide with differences in ice extent. An increase in precipitation in these regions may have had direct consequences on the glaciers' mass balance and equilibrium line altitudes, where the glaciers' effectiveness in erosion is highest (e.g. Egholm et al., 2009; Yanites and Ehlers, 2012). The differences in the direction of precipitation changes, and accompanying changes in ice cover would likely result in more regionally differentiated variations in precipitation-specific erosional processes in the St Elias Mountains rather than causing systematic offsets for the LGM. Although precipitation is significantly reduced along much of the Himalayan orogen (≤ 1600 mm a−1), northeastern India experiences strongly enhanced precipitation (≤ 1900 mm a−1). This could have large implications for studies of uplift and erosion at orogen syntaxes, where highly localised and extreme denudation has been documented (e.g. Koons et al., 2013; Bendick and Ehlers, 2014).

Overall, the PLIO climate is wetter than the PI climate, in particular in the (northern) mid-latitudes and is possibly related to a northward shift of the northern Hadley cell boundary that is ultimately the result of a reduced Equator-to-pole temperature gradient (e.g. Haywood et al., 2000, 2013; Dowsett et al., 2010). Most of the PLIO precipitation over land increases, especially at the Himalayan orogen by ≤ 1400 mm a−1, and decreases from eastern Nepal to Namcha Barwa (≤ 2500 mm a−1). Most of the Atacama Desert experiences an increase in precipitation by 100–200 mm a−1, which may have to be considered in erosion and uplift history reconstructions for the Andes. A significant increase (∼ 2000 mm a−1) in precipitation from simulation PLIO to modern conditions is simulated for the eastern margin of the Andean Plateau in Peru and for northern Bolivia. This is consistent with recent findings of a pulse of canyon incision in these locations in the last ∼ 3 Myr (Lease and Ehlers, 2013).

Overall, the simulated MH precipitation varies least from PI precipitation. The LGM is generally drier than the PI simulation, even though pockets of a wetter-than-PI climate do exist, such as much of coastal North America. Extratropical increased precipitation of the PLIO simulation and decreased precipitation of the LGM climate may be the result of decreased and increased Equator-to-pole temperature gradients, respectively.

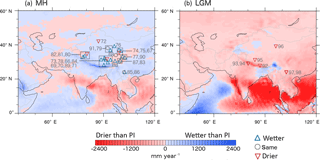

Figure 16Simulated annual mean precipitation deviations of MH (a) and LGM (b) from PI values in South Asia, and temporally corresponding proxy-based reconstructions, indicating wetter (upward facing blue triangles), drier (downward facing red triangles), or similar (grey circles) conditions in comparison with modern climate. MH proxy-based precipitation differences are taken from Mügler et al. (2010) (66), Wischnewski et al. (2011) (67), Mischke et al. (2008), Wischnewski et al. (2011), Herzschuh et al. (2009) (68), Yanhong et al. (2006) (69), Morrill et al. (2006) (70), Wang et al. (2002) (71), Wuennemann et al. (2006) (72), Zhang et al. (2011), Morinaga et al. (1993), Kashiwaya et al. (1995) (73), Shen et al. (2005) (74), Liu et al. (2014) (75), Herzschuh et al. (2006a) (76), Zhang and Mischke (2009) (77), Nishimura et al. (2014) (78), Yu and Lai (2014) (79), Gasse et al. (1991) (80), Van Campo et al. (1996) (81), Demske et al. (2009) (82), Kramer et al. (2010) (83), Herzschuh et al. (2006b) (84), Hodell et al. (1999) (85), Hodell et al. (1999) (86), Shen et al. (2006) (87), Tang et al. (2000) (88), Tang et al. (2000) (89), Zhou et al. (2002) (90), Liu et al. (1998) (91), Asashi (2010) (92), Kotila et al. (2009) (93), Kotila et al. (2000) (94), Wang et al. (2002) (95), Hu et al. (2014) (96), Hodell et al. (1999) (97), and Hodell et al. (1999) (98).

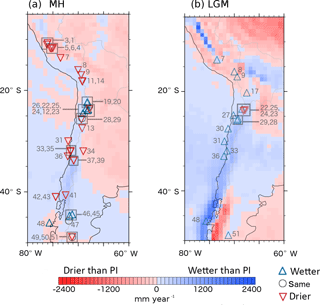

Figure 17Simulated annual mean precipitation deviations of MH (a) and LGM (b) from PI values in South America and temporally corresponding proxy-based reconstructions, indicating wetter (upward-facing blue triangles), drier (downward-facing red triangles), or similar (grey circles) conditions in comparison with modern climate. MH proxy-based precipitation differences are taken from Bird et al. (2011) (1), Hansen et al. (1994) (2), Hansen et al. (1994) (3), Hansen et al. (1994) (4), Hansen et al. (1994) (5), Hansen et al. (1994) (6), Hillyer et al. (2009) (7), D'Agostino et al. (2002) (8), Baker et al. (2001) (9), Schwalb et al. (1999) (10), Schwalb et al. (1999) (11), Schwalb et al. (1999) (12), Schwalb et al. (1999) (13), Moreno et al. (2009) (14), Pueyo et al. (2011) (15), Mujica et al. (2015) (16), Fritz et al. (2004) (17), Gayo et al. (2012) (18), Latorre et al. (2006) (19), Latorre et al. (2003) (20), Quade et al. (2008) (21), Bobst et al. (2001) (22), Grosjean et al. (2001) (23), Betancourt et al. (2000) (24), Latorre et al. (2002) (25), Rech et al. (2003) (26), Diaz et al. (2012) (27), Maldonado et al. (2005) (28), Diaz et al. (2012) (29), Lamy et al. (2000) (30), Kaiser et al. (2008) (31), Maldonado et al. (2010) (32), Villagrán et al. (1990) (33), Méndez et al. (2015) (34), Maldonado and Villagrán (2006) (35), Lamy et al. (1999) (36), Jenny et al. (2002b) (37), Jenny et al. (2002b) (38), Villa-Martínez et al. (2003) (39), Bertrand et al. (2008) (40), De Basti et al. (2008) (41), Lamy et al. (2009) (42), Lamy et al. (2002) (43), Szeicz et al. (2003) (44), de Porras et al. (2012) (45), de Porras et al. (2014) (46), Markgraf et al. (2007) (47), Siani et al. (2010) (48), Gilli et al. (2001) (49), Markgraf et al. (2003) (50), and Stine and Stine (1990) (51).

4.2.2 Precipitation comparison to other studies

The large-scale LGM precipitation decrease on land, related to cooling and decreased evaporation over the tropics, and greatly reduced precipitation along much of the Himalayan orogeny, is consistent with previous studies by, for example, Braconnot et al. (2007). The large-scale PLIO precipitation increase due to a reduced Equator-to-pole temperature gradient has previously been pointed out by Haywood et al. (2000, 2013) and Dowsett et al. (2010), for example. A reduction of this gradient by ca. 5 ∘C is indeed present in the PLIO simulation of this study (Fig. 2b). This precipitation increase over land agrees well with simulations performed at a lower spatial model resolution (see Stepanek and Lohmann, 2012). Section 4.4 includes a more in-depth discussion of how simulated MH and LGM precipitation differences compare with proxy-based reconstructions in South Asia and South America.

4.3 Trends in late Cenozoic changes in regional climatology

This section describes the major changes in regional climatology and highlights their possible implications on erosion rates.

4.3.1 Himalayas–Tibet, South Asia

In South Asia, cluster-analysis-based categorisation and description of climates (Fig. 6) remains similar throughout time. However, the two wettest climates (C1 and C2) are geographically more restricted to the eastern Himalayan orogen in the LGM simulation. Even though precipitation over the South Asia region is generally lower, this shift indicates that rainfall on land is more concentrated in this region and that the westward drying gradient along the orogen is more accentuated than during other time periods investigated here. While there is limited confidence in the global atmospheric GCM's abilities to accurately represent mesoscale precipitation patterns (e.g. Cohen, 1990), the simulation warrants careful consideration of possible, geographically non-uniform offsets in precipitation in investigations of denudation and uplift histories.

MH precipitation and temperature in tropical, temperate, and high-altitude South Asia are similar to PI precipitation and temperature, whereas LGM precipitation and temperature are generally lower (by ca. 100 mm a−1 and 1–2 ∘C, respectively), possibly reducing precipitation-driven erosion and enhancing frost-driven erosion in areas pushed into a near-zero temperature range during the LGM.

4.3.2 Andes, South America

Clusters in South America (Fig. 9), which are somewhat reminiscent of the Köppen and Geiger classification (Kraus, 2001), remain mostly the same over the last 3 Myr. In the PLIO simulation, the lower-altitude east of the region is characterised by four distinct climates, which suggests enhanced latitudinal variability in the PLIO climate compared to PI with respect to temperature and precipitation.

The largest temperature deviations from PI values are derived for the PLIO simulation in the (tropical and temperate) Andes, where temperatures exceed PI values by 5 ∘C. Conversely, LGM temperatures in the Andes are ca. 2–4 ∘C below PI values in the same region (Fig. 7g and h). In the LGM simulation, tropical South America experiences ca. 50 mm a−1 less precipitation; the temperate Andes receive ca. 50 mm a−1 more precipitation than in PI and MH simulations. These latitude-specific differences in precipitation changes ought to be considered in attempts to reconstruct precipitation-specific palaeoerosion rates in the Andes on top of longitudinal climate gradients highlighted by Montgomery et al. (2001), for example.

4.4 St Elias Mountains, southern Alaska

Southern Alaska is subdivided into two wetter and warmer clusters in the south and two drier, colder clusters in the north. The latter are characterised by increased seasonal temperature variability due to being located at higher latitudes (Fig. 12). The different Equator-to-pole temperature gradients for LGM and PLIO may affect the intensity of the Pacific–North American teleconnection (PNA; Barnston and Livzey, 1987), which has significant influence on temperatures and precipitation, especially in southeastern Alaska, and may in turn result in changes in regional precipitation and temperature patterns and thus on glacier mass balance. Changes in the Pacific Decadal Oscillation, which is related to the PNA pattern, has previously been connected to differences in late Holocene precipitation (Barron and Anderson, 2011). While this climate cluster pattern appears to be a robust feature for the considered climate states, and hence over the recent geologic history, the LGM sets itself apart from PI and MH climates by generally lower precipitation (20–40 mm) and lower temperatures (3–5 ∘C; Figs. 10, 11), which may favour frost-driven weathering during glacial climate states (e.g. Andersen et al., 2015; Marshall et al., 2015) in unglaciated areas, whereas glacial processes would have dominated most of this region as it was covered by ice. Simulation PLIO is distinguished by temperatures that exceed PI and MH conditions by ca. 2 ∘C and by larger temperature and precipitation value ranges, possibly modifying temperature- and precipitation-dependent erosional processes in the region of southern Alaska.

4.5 Cascade Range, US Pacific Northwest

In all time slices, the geographic climate patterns, based on the cluster analysis (Fig. 15), represent an increase in the degree of continentality from the wetter coastal climates to the further inland climates with greater seasonal temperature amplitude and lower precipitation and precipitation amplitude (Fig. 15e–h). The most notable difference between the time slices is the strong cooling during the LGM, when temperatures are ca. 13 ∘C (Figs. 13, 14) below those of other time periods. Given that the entire investigated region was covered by ice (Fig. 13), we can assume a shift to glacially dominated processes.

4.6 Comparison of simulated and observed precipitation differences

The predicted precipitation differences reported in this study were compared with observed (proxy record) palaeoprecipitation change. Proxy-based precipitation reconstructions for the MH and LGM are presented for South Asia and South America for the purpose of assessing ECHAM5 model performance and for identifying inconsistencies among neighbouring proxy data. Due to the repeated glaciations, detailed terrestrial proxy records for the time slices investigated here are not available, to the best of our knowledge, for the Alaskan and Pacific NW USA studies. Although marine records and records of glacier extent are available in these regions, the results from them do not explicitly provide estimates of wetter–drier or colder–warmer conditions that can be spatially compared to the simulation estimates. For these two areas with no available records, the ECHAM5-predicted results therefore provide predictions from which future studies can formulate testable hypotheses to evaluate.

The palaeoclimate changes in terrestrial proxy records compiled here are reported as “wetter than today”, “drier than today”, or “the same as today” for each of the study locations and plotted on top of the simulation-based difference maps as upward-facing blue triangles, downward-facing red triangles, and grey circles, respectively (Figs. 16, 17). The numbers listed next to those indicators are the ID numbers assigned to the studies compiled for this comparison and are associated with a citation provided in the figure captions.

In South Asia, 14 out of 26 results from local studies agree with the model-predicted precipitation changes for the MH. The model seems able to reproduce the predominantly wetter conditions on much of the Tibetan Plateau, but predicts slightly drier conditions north of Chengdu, which is not reflected in local reconstructions. The modest mismatch between ECHAM5-predicted and proxy-based MH climate change in South Asia was also documented by Li et al. (2017), whose simulations were conducted at a coarser (T106) resolution. Despite these model–proxy differences, we note that there are significant discrepancies among the proxy data themselves in neighbouring locations in the MH, highlighting caution in relying solely upon these data for regional palaeoclimate reconstructions. These differences could result from either poor age constraints on the reported values or systematic errors in the transfer functions used to convert proxy measurements to palaeoclimate conditions. The widespread drier conditions on the Tibetan Plateau and immediately north of Laos are confirmed by seven out of seven of the palaeoprecipitation reconstructions. Of the reconstructed precipitation changes, 23 out of 39 agree with model predictions for South America during the MH. The model-predicted wetter conditions in the central Atacama Desert, as well as the drier conditions northwest of Santiago are confirmed by most of the reconstructions. The wetter conditions in southernmost Peru and the border to Bolivia and Chile cannot be confirmed by local studies. Of the precipitation reconstructions, 11 out of 17 for the LGM are in agreement with model predictions. These include wetter conditions in most of Chile. The most notable disagreement can be seen in northeastern Chile at the border to Argentina and Bolivia, where model-predicted wetter conditions are not confirmed by reported reconstructions from local sites.

Model performance is, in general, higher for the LGM than for the MH and overall satisfactory given that it cannot be expected to resolve sub-grid-scale differences in reported palaeoprecipitation reconstructions. However, as mentioned above, it should be noted that some location (MH of South Asia, and MH of norther Chile) discrepancies exist among neighbouring proxy samples and highlight the need for caution in how these data are interpreted. Other potential sources of error resulting in disagreement of simulated and proxy-based precipitation estimates are the model's shortcomings in simulating orographic precipitation at higher resolutions, and uncertainties in palaeoclimate reconstructions at the local sites. In summary, although some differences are evident in both the model–proxy data comparison and among neighbouring proxy data themselves, the comparison above highlights an overall good agreement between the model and data for the South Asia and South American study areas. Thus, although future advances in GCM model parameterisations and new or improved palaeoclimate proxy techniques are likely, the palaeoclimate changes documented here are found to be in general robust and provide a useful framework for future studies investigating how these predicted changes in palaeoclimate impact denudation.

We present a statistical cluster-analysis-based description of the geographic coverage of possible distinct regional expressions of climates from four different time slices (Figs. 6, 9, 12, 15). These are determined with respect to a selection of variables that characterise the climate of the region and may be relevant to weathering and erosional processes. While the geographic distribution of climate remains similar throughout time (as indicated by results of four different climate states representative for the climate of the last 3 Myr), results for the PLIO simulation suggests more climatic variability east of the Andes (with respect to near-surface temperature, seasonal temperature amplitude, precipitation, seasonal precipitation amplitude and seasonal u-wind and v-wind speeds). Furthermore, the wetter climates in the South Asia region retreat eastward along the Himalayan orogen for the LGM simulation; this is due to decreased precipitation along the western part of the orogen and enhanced precipitation on the eastern end, possibly signifying more localised high erosion rates.

Most global trends of the high-resolution LGM and PLIO simulations conducted here are in general agreement with previous studies (Otto-Bliesner et al., 2006; Braconnot et al., 2007; Wei and Lohmann, 2012; Lohmann et al., 2013; R. Zhang et al., 2013, 2014; Stepanek and Lohmann, 2012). The MH does not deviate notably from the PI, the LGM is relatively dry and cool, while the PLIO is comparably wet and warm. While the simulated regional changes in temperature and precipitation usually agree with the sign (or direction) of the simulated global changes, there are region-specific differences in the magnitude and direction. For example, the LGM precipitation of the tropical Andes does not deviate significantly from PI precipitation, whereas LGM precipitation in the temperate Andes is enhanced.

Comparisons to local, proxy-based reconstructions of MH and LGM precipitation in South Asia and South America reveal satisfactory performance of the model in simulating the reported differences. The model performs better for the LGM than the MH. We note however that compilations of proxy data such as we present here also identify inconsistences among neighbouring proxy data themselves, warranting caution in the extent to which both proxy data and palaeoclimate models are interpreted for MH climate change in South Asia and western South America.