the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Cirque-like alcoves in the northern mid-latitudes of Mars as evidence of glacial erosion

Michelle R. Koutnik

Stephen Brough

Matteo Spagnolo

Iestyn Barr

Viscous flow features known as glacier-like forms on Mars have been observed emerging from alcoves that resemble cirques on Earth. However, many alcoves exist without associated glacier-like forms, and these features have never been studied or categorized at a regional population scale. On Earth, cirques form when depressions on mountain slopes accumulate snow, which gradually compacts into glacial ice. As the glacier flows downhill, it deepens the depression through erosion. Most of this erosion is driven by wet-based glaciers, although cold-based glaciers can also contribute to some headward and sidewall retreat. Here, we present evidence that cirque-like alcoves on Mars, similar to terrestrial cirques, are shaped by glacial erosion. To assess which alcoves on Mars are most “cirque-like”, we mapped a regional population of ∼ 2000 alcoves in Deuteronilus Mensae (40–48° N, 16–35° E), a region in the mid-latitudes of Mars characterized by mesas surrounded by glacial remnants. Based on visual characteristics and morphometrics, we refined our dataset to 434 “cirque-like alcoves” – nearly six times the amount of glacier-like forms in the region – and used this to better understand the potential contribution of glaciation to landscape evolution in Deuteronilus Mensae, Mars. High-resolution imagery reveals geomorphic evidence for past glacial occupation of these cirque-like alcoves, including flow features, linear terrain, moraine-like ridges, mound-and-tail terrain, polygonal terrain, rectilinear-ridge terrain, and washboard terrain, as well as an ice-rich mantling unit. Most cirque-like alcoves face south to southeast, similar to gullies poleward of 40°. One possibility to explain this trend is that southward facing cirque-like alcoves in the northern mid-latitudes formed when conditions were more favorable for ice accumulation during periods of high obliquity. Using wet-based glacial erosion rates, assuming a mean annual temperature of 0 °C (compared to present-day temperatures of °C), the timescales for Martian cirque-like alcove formation align with both the estimated ages of glacier-like forms (millions to tens of millions of years) and other viscous flow features such as lobate debris aprons (hundreds of millions of years). In contrast, using a temperature assumption of −50 to −68 °C, cold-based erosion rates are only consistent with the older ages of lobate debris aprons. By mapping cirque-like alcoves at a large scale for the first time, we expand the catalog of features attributed to glacial erosion on Mars. Future work is needed to specify the timing of the formation of cirque-like alcoves and whether their formation required warm-based erosion.

- Article

(31142 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The surface morphology of the mid-latitudes of Mars (especially between 30 and 60°, north and south) is characterized by glacial remnants in the form of subsurface ice (Fig. 1; e.g., Brough et al., 2019; Levy et al., 2014), and icy mantling deposits (Mustard et al., 2001). The geologic history of Mars is divided into three main epochs: the Noachian around 4.0 to 3.85 Ga, the Hesperian around 3.56 to 3.24 Ga, and the Amazonian around 3.24 Ga to present-day (e.g., Hartmann, 2005; Michael, 2013; Kite, 2019). Observations and modeling suggest that the climate of the past 3 Gyr was unlikely to have permitted widespread liquid water on the planet's surface, though spatially-limited liquid may have occurred under some conditions (e.g., Kite, 2019). Glacial remnants in the mid-latitudes of Mars, referred to as viscous flow features, are typically considered to have always been frozen to their beds (cold-based) with limited subglacial erosion, and ice flow occurred only by internal deformation and gravity-driven viscous creep throughout their evolution (e.g., Mangold and Allemand, 2001; Head and Marchant, 2003; Shean et al., 2005; Mackay et al., 2014). Previous work has estimated cold-based erosion rates of 0.1–10 m Myr−1 during Amazonian glaciation on Mars (Levy et al., 2016). However, the presence of glacial landforms such as moraines and lineations observed in tandem with some viscous flow features suggests subglacial erosion could have occurred and that the thermal regime over the evolution of these landforms could have been formerly wet-based or at least a mixed thermal state like polythermal (e.g., Arfstrom and Hartmann, 2005; Morgan et al., 2009; Hubbard et al., 2011; Hubbard et al., 2014; Gallagher et al., 2021). In addition, recent work proposed that some depositional and erosional evidence of wet-based glaciation within the last 1 Gyr (Middle to Late Amazonian) exists, especially in the form of eskers, which would indicate warmer subglacial conditions at these sites (e.g., Gallagher and Balme, 2015; Butcher et al., 2017, 2021; Gallagher et al., 2021, Woodley et al., 2022). Englacial debris bands have been found in some viscous flow features, though it is unclear if the debris is from rockfall at the headwall or eroded and then entrained from the subglacial bed (e.g., Butcher et al., 2024; Levy et al., 2021).

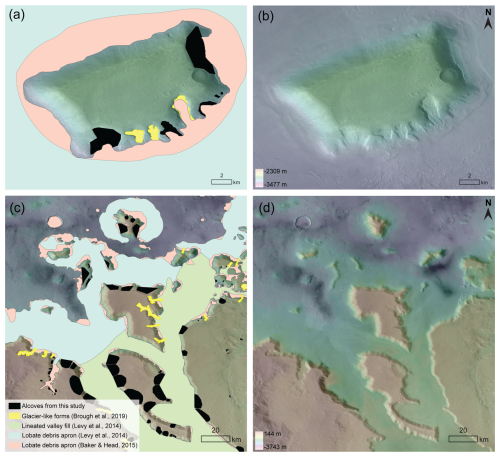

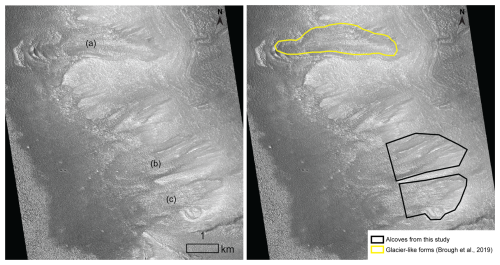

Figure 1Examples of alcoves mapped in this study and viscous flow features mapped in prior studies. Legend in the bottom left applies to panels (a) and (c). Black-filled polygons are alcoves mapped as part of this study, yellow-filled polygons are previously mapped glacier-like forms (Brough et al., 2019), blue represents the previously mapped lobate debris apron (Levy et al., 2014), and pink represents an updated map of lobate debris apron (Baker and Head, 2015). Note that there is some overlap between what previous studies generally classified as lobate debris aprons and what Brough et al. (2019) later specifically defined as glacier-like forms. Green-filled polygons represent lineated valley fill mapped by Levy et al. (2014). (a) Standalone mesa in Deuteronilus Mensae, centered at 45.5° N, 26.3° E. (b) The same mesa as in (a) but without mapped units delineated. The basemap is the CTX mosaic (Dickson et al., 2018) overlaid on a High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC) (Neukum and Jaumann, 2004) digital elevation model (DEM) that was mosaicked from 29 frames, which are listed in the Data Availability section. (c) A zoomed out view of all alcoves (not just cirque-like alcoves) mapped in a sub-region of the study area. The area is centered at 41.5° N, 34.0° E. (d) Same area as in (c) but without mapped units delineated. CTX data credit: Caltech/NASA/JPL/MSSS. HRSC data credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin.

Viscous flow features include the landform classifications of glacier-like forms (Souness et al., 2012), lobate debris aprons, lineated valley fill, and concentric crater fill (e.g., Squyres, 1979; Milliken et al., 2003; Levy et al., 2014). In the cases where subsurface radar sounding data are available, lobate debris aprons consist of up to ∼ 90 % ice (Holt et al., 2008; Plaut et al., 2009), and they account for ∼ 63 % of the total volume of ice contained within all viscous flow features (Levy et al., 2014). Lobate debris aprons can be a few to tens of kilometers long and up to one kilometer thick (Holt et al., 2008; Plaut et al., 2009). In comparison, glacier-like forms are generally smaller, on average ∼ 4.66 km long, ∼ 1.27 km wide (Souness et al., 2012), and ∼ 130 m thick (Brough et al., 2019). All mid-latitude viscous flow features are believed to have been deposited during orbital excursions of ≥35° in the Amazonian (Madeleine et al., 2009). Lobate debris aprons, lineated valley fills, and concentric crater fills are estimated to range from ∼ 10 Myr to 1.1 Gyr in age (Morgan et al., 2009; Berman et al., 2015), with most age estimations on the order of hundreds of millions of years (e.g., 300–800 Myr from Fassett et al., 2014). Glacier-like forms can superpose lobate debris aprons or lineated valley fills, suggesting polyphase glaciation with age clusters estimated to be around 2–20 and 45–65 Myr (Hepburn et al., 2020). In addition to viscous flow features, there is a separate icy mantling deposit over the mid-latitudes originating from airfall deposits of ice nucleated on dust, known as the latitude-dependent mantle (e.g., Mustard et al., 2001; Kreslavsky and Head, 2002; Schon et al., 2009; Conway et al., 2018). The latitude-dependent mantle consists of different layers rich in water ice and dust (Schon et al., 2009). The ice was deposited during high obliquity excursions and the dust formed during low obliquities when the ice sublimated and left behind a dusty lag (Schon et al., 2009). Although the mantling unit covers >23 % of the surface of Mars (Kreslavsky and Head, 2002), with thickness estimates ranging from 1–30 m thick (Mustard et al., 2001; Conway and Balme, 2014), the mantling unit represents a small contribution (103–104 km3) to the overall ice volume (Conway and Balme, 2014). In some locations the mantling unit has been mapped as “pasted-on terrain”, though it remains unclear whether the pasted-on terrain is a thicker mantling layer that is separate from an overlying mantle (Conway et al., 2018). The icy mantling unit is estimated to be younger than glacier-like forms at 0.15 to 10 Myr in age (Willmes et al., 2012; Schon et al., 2012).

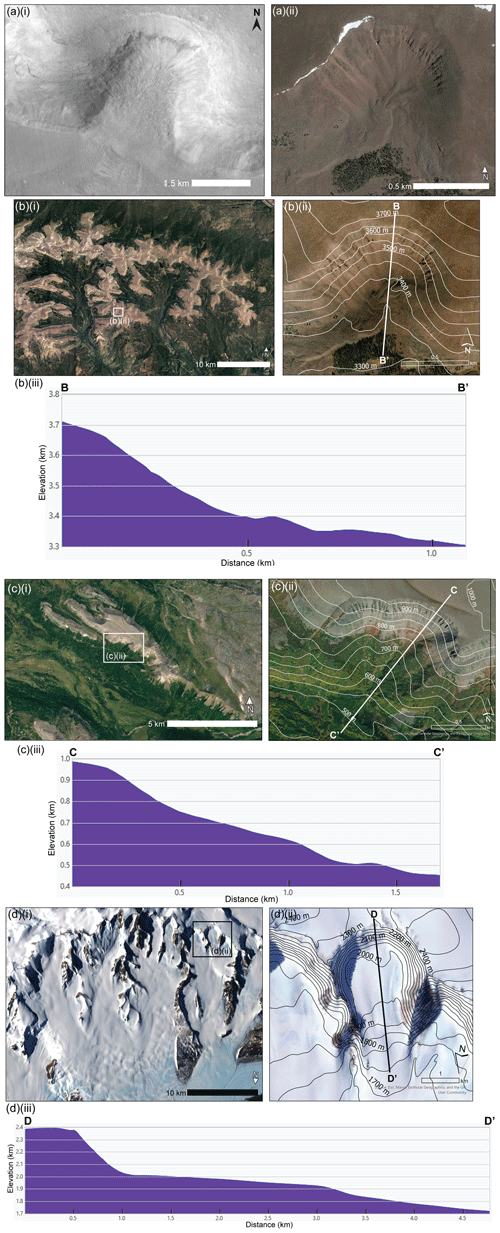

Figure 2Example of a cirque-like alcove on Mars alongside cirques from different regions on Earth. (a)(i) Example of a cirque-like alcove on Mars (40.24° N, 34.48° E) (CTX mosaic; Dickson et al., 2018) (a)(ii) a cirque on Earth in the Uinta Mountains (40.712° N, 110.114° W). CTX data credit: Caltech/NASA/JPL/MSSS. Earth imagery is from ©Google Earth including Landsat/Copernicus/U.S. Geological Survey coverage. (b–d) Examples of cirques on Earth incised into mesa topography, along with an example of a cirque profile in each. Images are from ESRI World Imagery. Part (i) of (b)–(d) provides an overview of the cirques in that location with an inset of the location of part (ii). Part (ii) of (b)–(d) offers a zoomed-in view of an individual cirque. Part (iii) of (b)–(d) shows the profile of the individual cirques in part (ii). (b) Uinta Mountains, Utah, USA (40.74° N, 110.05° W), same location as (a)(ii). DEM data: National Elevation Dataset, access via The National Map (Gesch et al., 2002). (c) Kamchatka Peninsula, Russia (58.48° N, 160.70° E). DEM data: Shuttle Radar Topography Mission, access via EarthExplorer (NASA SRTM, 2013). (d) Transantarctic Mountains, Antarctica (80.01° S, 156.35° E). DEM data: Reference Elevation Model of Antarctica (Howat et al., 2022), access via the Polar Geospatial Center.

Glacial cirques on Earth are characterized by a concave basin connected to a steep headwall, often with a threshold or lip of higher topography at the lower end of the basin (Fig. 2). Cirques develop from incipient depressions in mountain and plateau sides that fill with snow/ice and over time support active glaciers that deepen the depressions by glacial erosion (Evans and Cox, 1974; Glasser and Bennett, 2004). This occurs via a combination of basal slip, quarrying, abrasion (e.g., White, 1970), and frost weathering (e.g., Sanders et al., 2012), which all contribute toward a tendency for rotational flow (Evans, 2020). However, it is debated whether non-glacial processes such as rock-slope failures may have a substantial contribution to erosion as well (e.g., Turnball and Davies, 2006; Coquin et al., 2019; Evans, 2020). Due to their presence at high topographic locations on Earth and due to their concave shape, cirques trap snow and ice and are often the first sites to glaciate and the last sites to deglaciate (Graf, 1976). On Earth, with over 10 000 glacial cirques mapped globally, landform morphometrics are used to reveal regional climatic trends and the extent of glaciation in the past (e.g., Mîndrescu et al., 2010; Evans, 2006; Barr and Spagnolo, 2015).

Previous work described that glacier-like forms on Mars are formed in and extend out of “cirque-like alcoves” and that it is unknown whether the glacier-like forms and/or any ice masses that came before them were wet-based (Hubbard et al., 2014). Herein, we use the term “alcove” loosely to describe any hollow with an arcuate headwall and opening downslope, on the scale of hundreds of meters to a few kilometers in width and length. Hypothesized cirques on Mars have been identified in the mid-latitudes (Gallagher et al., 2021) and equatorial regions (Davila et al., 2013; Bouquety et al., 2019; Williams et al., 2023). While the alcoves in areas such as Deuteronilus Mensae have been interpreted as potentially connected to past glaciation (e.g., Head et al., 2006; Morgan et al., 2009; Hubbard et al., 2011; Souness and Hubbard, 2013), there have not been any in-depth studies dedicated to identifying cirque-like alcoves on a regional population scale. In this study, we mapped 1991 alcoves in Deuteronilus Mensae in the northern mid-latitudes of Mars and conducted a morphometric analysis to narrow them down to 434 cirque-like alcoves. We evaluate the presence of geomorphic features as evidence for past glacial occupation of these cirque-like alcoves, their aspect as a population, and how they compare to other features such as glacier-like forms and gullies. Through mapping cirque-like alcoves at a large scale for the first time, we expand the extent of features attributed to glacial erosion on Mars.

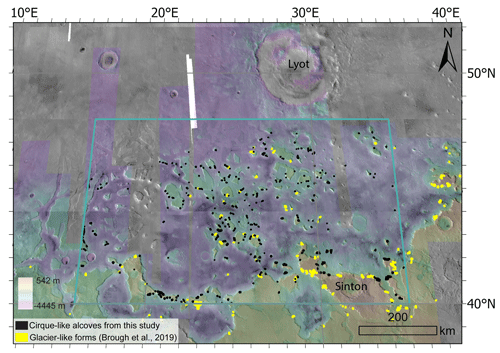

Figure 3The study region Deuteronilus Mensae in the northern mid-latitudes of Mars is within the teal box (40–48° N, 16–35° E). Colors represent mosaicked HRSC DEM data (specific frames and the mosaic are provided in the Data Availability section). The white sections toward the top left show where the CTX beta01 mosaic does not have coverage and grayscale areas of the map show where the mosaicked HRSC DEM does not have coverage. The major surface features Lyot Crater and Sinton Crater are noted. Yellow polygons represent 74 glacier-like forms from previous work (Brough et al., 2019), and the black polygons represent the distribution of 434 cirque-like alcoves mapped in this work. Note that while glacier-like forms (Brough et al., 2019) and cirque-like alcoves exist outside of the teal boundary lines, they are not included in the analyses reported in this study. CTX data credit: Caltech/NASA/JPL/MSSS. HRSC data credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin.

Our study region covers ∼ 600 000 km2 of Deuteronilus Mensae in the northern mid-latitudes of Mars (40–48° N, 16–35° E) (Fig. 3). While we also observe alcoves in other regions in the mid-latitudes of Mars, we focus on Deuteronilus Mensae as a study region for identifying cirque candidates due to its high density of icy viscous flow features (e.g., Levy et al., 2014; Baker and Carter, 2019; Brough et al., 2019). In addition to lobate debris aprons observed by the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter SHAllow RADar (SHARAD) instrument (e.g., Plaut et al., 2009; Baker and Carter, 2017), recently, the Mars Subsurface Water Ice Mapping project identified Deuteronilus Mensae as one of the regions on Mars where available data is highly consistent with the presence of subsurface ice at the regional scale (Morgan et al., 2021), Thus, Deuteronilus Mensae is a location of interest for future human missions to Mars (e.g., Morgan et al., 2021). Deuteronilus Mensae is characterized by terrain hosting valleys and mesas encompassed by remnants from previous glaciations (Sharp, 1973; Squyres, 1978; Carr, 2001; Morgan et al., 2009). Previous geomorphic mapping estimated that the mesas date back to the ancient Noachian and the plains to the Hesperian, while younger Amazonian sedimentary deposits and a mantling unit overlay the mesas (e.g., Baker and Carter, 2019). Much of the mantling unit also overlies the viscous flow features in the region (Baker and Head, 2015; Baker and Carter, 2019). These viscous flow features likely formed in the Middle to Late Amazonian (Head et al., 2010).

3.1 Alcove Mapping

We mapped 1991 alcoves at a 1 : 30 000 scale using the ∼ 6 m/pixel Context Camera imagery beta01 mosaic (Malin et al., 2007; Dickson et al., 2018). We only map alcoves that do not contain previously mapped glacier-like forms (Fig. 1). We did allow overlap with previous mapping of lobate debris apron and lineated valley fill because boundaries for these lobate debris aprons and lineated valley fill were different between Baker and Head (2015) and Levy et al. (2014). In addition, it was not always clear how the mapped boundaries for the lobate debris aprons and lineated valley fills were decided on relative to where the alcoves and mesa sidewalls were located. As a result, we mapped alcoves regardless of where the boundaries for the lobate debris aprons and lineated valley fills were drawn. We digitized the outlines of the alcoves using ArcGIS software. Measurements from all the imagery and DEMs were projected to use a Sinusoidal projection centered on longitude 25.5° E, and were based on the International Astronomical Union (IAU) Mars 2000 datum, treating Mars as an ellipsoid. For morphometric analyses, we used a High Resolution Stereo Camera (HRSC; Neukum and Jaumann, 2004) digital elevation model (DEM) of 29 frames mosaicked together that comprises a true resolution of 100 m/pixel (see Data Availability section for exact frames). The HRSC DEMs were mosaicked together using the Mosaic to New Raster tool in ArcGIS Pro using the method of “Last”, which is where the output cell value of the overlapping areas will be the value from the last raster dataset mosaicked into that location. The pixel size of the resulting DEM was 100 m. No alignment was performed, however, we assessed the alignment by examining 20 random points across boundaries of various HRSC frames and found the difference to be negligible because the average percent change was only 0.86 %. Where available, we used ∼ 25 cm/pixel High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment (HiRISE; McEwen et al., 2007) images to examine glacial geomorphic features within and related to features coming out of the alcoves, which are listed in the Data Availability section.

3.2 Criteria for Identification of Cirque-like Alcoves

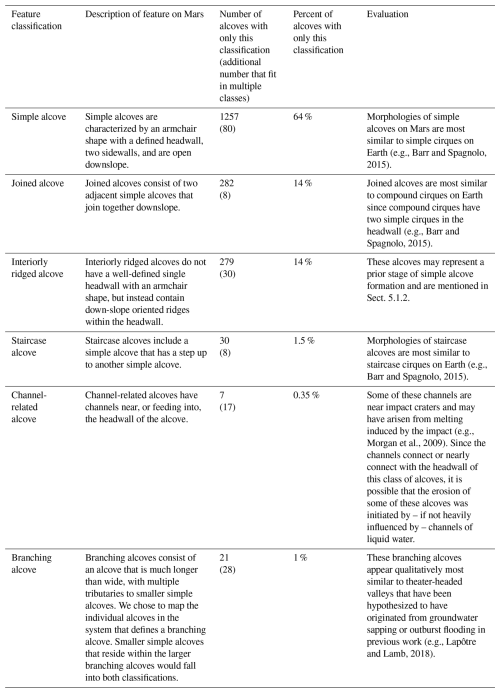

3.2.1 Alcove Classes

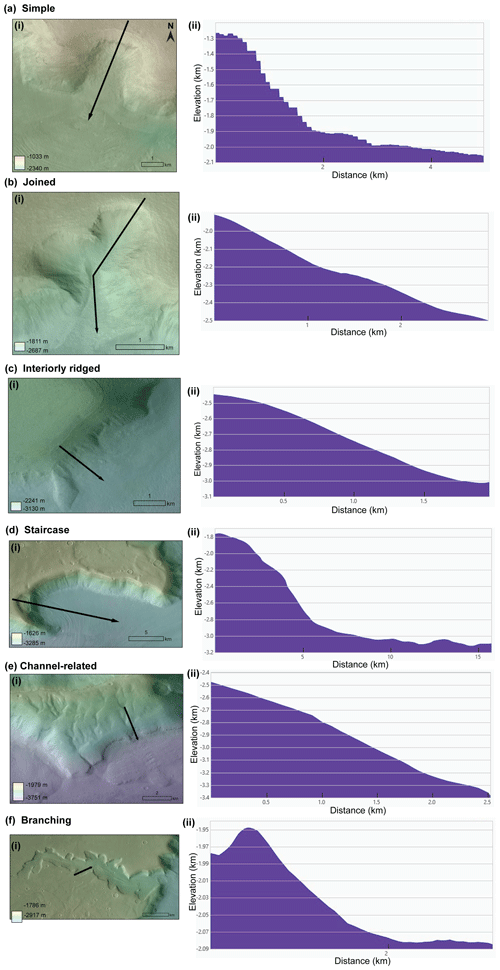

Cirques on Earth are categorized into five grades ranging from a “classic” cirque that contains “textbook” attributes to a “marginal” cirque, where the cirque status is doubtful (Evans and Cox, 1995). In addition, there are also numerous cirque types including simple cirques, compound cirques, cirque complexes, staircase cirques, and cirque troughs (Benn and Evans, 2010), which we drew upon to inform our preliminary alcove classes for our Deuteronilus Mensae analyses. Based on their kilometer-scale physical characteristics including shape, size, and associated landforms as seen in CTX imagery, alcoves that show any of the following morphologies: (a) joined, (b) interiorly ridged, (c) staircase, (d) channel-related, and (e) branching were not included in our database. Descriptions and interpretations of these morphologies are provided in Appendix A. Although terrestrial glacial cirques may also fall into different categories, for our study of Martian alcoves that are considered most analogous to terrestrial cirques, we focus on the alcoves classified as simple alcoves (and that do not have any of the morphologies listed above). Like simple cirques on Earth, simple alcoves on Mars are characterized by an armchair shape with an identifiable headwall, two sidewalls, and an opening downslope.

3.2.2 Alcove Morphometric Calculations

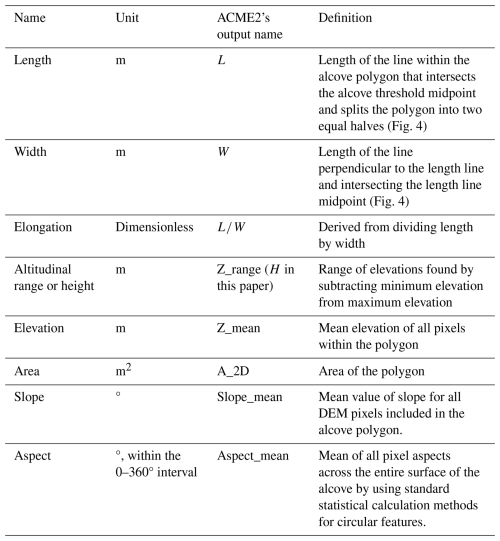

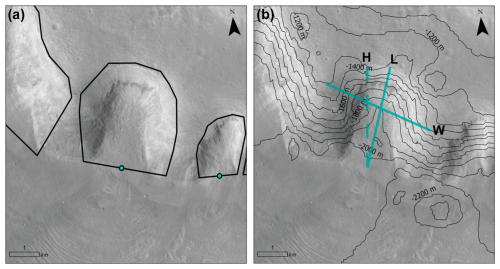

We applied the Automated Cirque Metric Extraction (ACME2; Spagnolo et al., 2017; Li et al., 2024) tool in ArcGIS Pro to calculate alcove morphometrics, specifically, length (L), width (W), elongation (), altitudinal range or height (H; difference between maximum and minimum elevation), area, slope, mean elevation, and aspect (Table 1). We approximate the total cavity volume of the alcove by multiplying the length, width, and height (LWH) and find the “size” by then taking the cube root of volume: , following previous work (e.g., Barr and Spagnolo, 2015). Here we find the total cavity volume of the alcoves as a proxy for the maximum amount of ice that the alcoves may have contained, which is likely an overestimate since it assumes the alcove is round. To use the ACME2 tool, we provided the mapped shape of the alcove, a threshold midpoint, which is defined as the midpoint of the down-valley lip of the cirque, and the mosaicked HRSC DEM as inputs (Fig. 4). ACME2 outputs the morphometrics into the attribute table of the feature class for alcoves.

On Earth, typical cirque ratios are 0.5–4.25 (Derbyshire and Evans, 1976), and based on 10 362 globally distributed cirques, both and ratios typically range between 1.5 to 4.0 (Barr and Spagnolo, 2015). Note that by only including ratios between 1.5 to 4.0, we expect that craters are excluded since craters typically have depth-to-diameter ratios of 0.1–0.2 (e.g., Robbins and Hynek, 2012), i.e., ratios of 5:1 and 10:1. By using morphometrics, we also exclude other types of mechanisms for alcove formation, including deep-seated landslides, and amphitheater-headed valleys (Table 2). This is because the ratio of a terrestrial glacial cirque is expected to be deeper than any of the other alcove landforms with known morphometrics on Earth (Table 2). We focus only on the simple alcoves (based on morphology) that have these morphometric ranges for , , and to constrain the most “cirque-like” alcoves in Deuteronilus Mensae, Mars. By applying these constraints, we were able to identify 434 cirque-like alcoves after downsampling from our initial mapping and classification based on only image analysis of 1991 alcoves. Herein, we use the term “cirque-like alcove” for the Martian alcoves that we will evaluate in this study as candidate cirques shaped by glacial erosion.

Table 1Alcove morphometrics as outputted by the Automated Cirque Metric Extraction (ACME2) tool. The content was modified from Spagnolo et al. (2017) and Li et al. (2024).

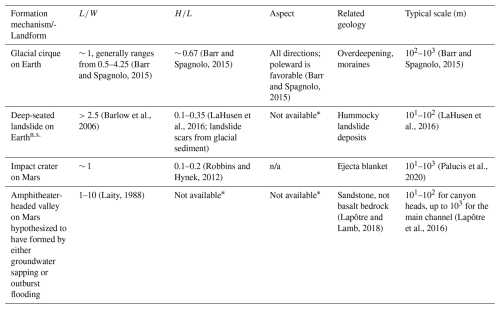

Table 2Morphometrics consistent with different alcove-forming erosional mechanisms on Earth and Mars.

Not available *: As of writing this paper, focused studies on the morphometrics of these landforms on the population scale are not available. : “n.s.” stands for “not scarp” since landslide morphometrics do not usually include measurements of the morphometrics of just the headscarp and sidewalls of where the landslides initiated. n/a: Not applicable. Aspect is not applicable for craters, which are fully rounded.

Figure 4(a) Inputs for the Automatic Cirque Metric Extraction (ACME2) tool (Spagnolo et al., 2017; Li et al., 2024) include a shapefile for the alcove, a teal point for the alcove threshold, as pictured here, and a DEM. (b) Outputs from ACME2 include morphometrics such as the length (L), width (W), and height (H) of the alcove (see Table 1). Teal lines represent the dimensions of the morphometrics L, W, and H. Black contours are from the mosaicked HRSC DEM. CTX data credit: Caltech/NASA/JPL/MSSS. HRSC data credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin.

3.2.3 Uncertainties in elevation and aspect

We mapped the cirque-like alcoves and identified the mid-threshold points using the CTX imagery. As mentioned in Sect. 3.1, both the CTX imagery and mosaicked HRSC DEM were projected to a Sinusoidal projection centered on a longitude of 25.5° E, and were based on the IAU Mars 2000 datum with the major axis of the IAU ellipsoid. To evaluate any potential error introduced by misalignment between the CTX imagery and mosaicked HRSC DEM, we compared a CTX DEM to the mosaicked HRSC DEM for nine cirque-like alcoves. The CTX DEM that included coverage of nine cirque-like alcoves had the identification number j02_045640_2209_xn_ 40n339w_j16_ 050901_2209_xn_40n339w. We found the average percent changes for these nine cirque-like alcoves between the two DEMs to be 2.55 % for height, 6.44 % for aspect, and 2.35 % for slope. Since these percent changes were minimal, all less than 7 %, we determine that the mosaicked HRSC DEM is an accurate method to evaluate the cirque-like alcoves.

To assess whether the aspect was affected by inherent biases in the topography, we normalized the values. We found the relative percentages of cirque-like alcoves in each aspect bin after normalizing by the percent of the total land surface with slopes ≥18.4°, which includes slopes higher than the first quartile of the slopes of the cirque-like alcoves, in each aspect bin. We did this by finding aspect and slope rasters from the mosaicked HRSC DEM using the Surface Parameters tool in ArcGIS Pro. Next, we used the Raster to Point tool for the slope raster for slopes ≥18.4°. Then we used the Extract Multi Values to Points tool to find the associated aspect for each point before exporting the data to analyze with Python. Finally, we binned the data by aspect and divided the percent of cirque-like alcoves in each aspect bin by the sloped land surface percent bins and got the normalized percentages.

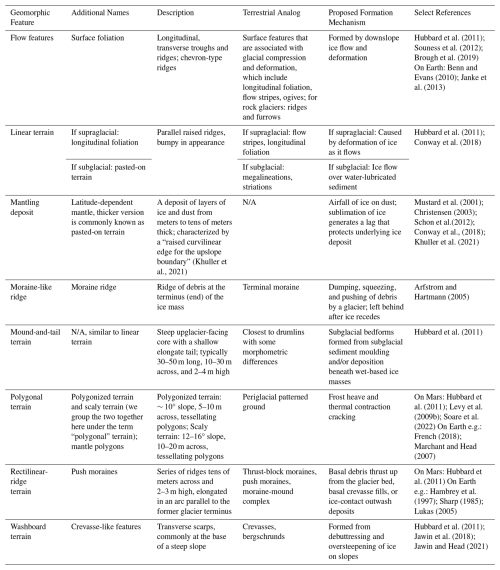

3.3 Criteria for identification of geomorphic features as evidence for past ice

In addition to mapping and calculating the morphometrics of alcoves in Deuteronilus Mensae, we also evaluate the presence of geomorphic evidence related to ice in the alcoves where HiRISE imagery is available. While we designed the study so that none of the cirque-like alcoves that we mapped included mapped glacier-like forms, using the available inventory of HiRISE images we observed other features associated with the cirque-like alcoves that appear consistent with the presence of ice or ice loss. The geomorphic features that we evaluate for in HiRISE images include flow features, linear terrain, mantling deposit, moraine-like ridges, mound-and-tail terrain, polygonal terrain, rectilinear-ridge terrain, and washboard terrain. We identify these features using the criteria listed in Table 3. In CTX imagery, we were also able to identify flow features, linear terrain, mantling deposit, moraine-like ridges, and washboard terrain. However, at the CTX resolution, it was more difficult to identify features such as mound-and-tail terrain, polygonal terrain, and rectilinear-ridge terrain. Other geomorphic features connected to the presence of ice that were observed near alcoves but not categorized in this study because they were not directly in or connected to features coming out of alcoves included brain terrain (Levy et al., 2009a) and pitted terrain (Jawin et al., 2018). We note that the geomorphic features that we identify may correspond to some of the criteria defined by Souness et al. (2012) for mapping glacier-like forms, which include: (1) surrounded by topography indicative of flow around obstacles, (2) distinct from the surrounding landscape in texture or color, (3) surface foliation indicative of down-slope flow, (4) ratio >1, (5) discernible head or terminus, (6) appear to contain a volume of ice. However, the geomorphic features noted here do not include all the criteria and were not previously mapped as glacier-like forms. For example, an icy feature within an alcove might appear to have a terminus, but no convexity from existing ice volume that differentiates it from surrounding topography (Fig. 5).

Figure 5(a) Previously mapped glacier-like form (Brough et al., 2019). (b) and (c) represent previously unmapped cirque-like alcoves which no longer appear to contain a volume of ice. While the unmapped cirque-like alcoves have arcuate features similar to moraine-like ridges that indicate past glacial ice, these arcuate features no longer have significant vertical relief. However, they do still contain surface foliations suggesting down-slope flow near the headwall. Cirque-like alcove mapping only extends to where the sidewalls end. This HiRISE image ESP_025873_2230_RED is centered at 42.63° N, 25.02° E. HiRISE data credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona.

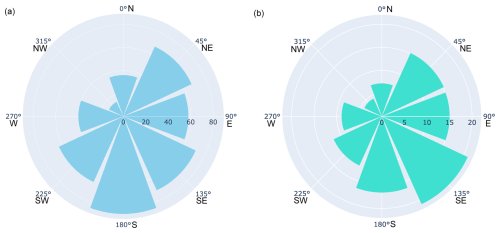

Figure 6(a) Rose diagram showing the aspect of cirque-like alcoves. Cirque-like alcove aspect averages 153.09° between the south and southeast directions. (b) Rose diagram showing the relative percentages of cirque-like alcoves in each aspect bin after normalizing by the percent of the total land surface with slopes ≥18.4° (slopes greater than the first quartile of the slopes of the cirque-like alcoves) in each aspect bin (the method is explained in Sect. 3.2.3). After normalizing, we found that the southeastward trend persisted and became more apparent. Aspect bins are as follows: 337.5≤ N <22.5°; 22.5≤ NE <67.5°; 67.5≤ E <112.5°; 112.5≤ SE <157.5°; 157.5≤ S <202.5°; 202.5≤ SW <247.5°; 247.5≤ W <292.5°; 292.5≤ NW <337.5.

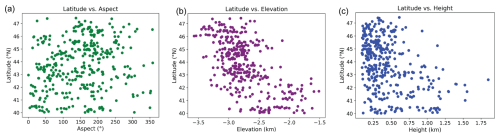

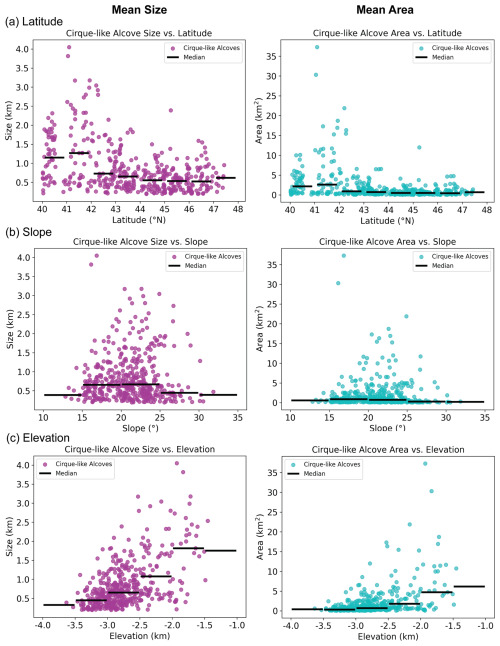

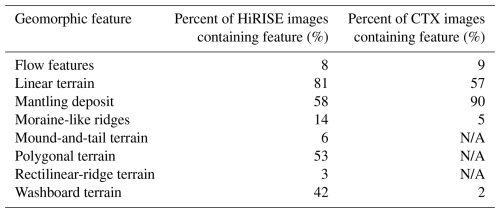

4.1 Trends in aspect, size, area, latitude, slope, and elevation of cirque-like alcoves

By examining the aspect of the regional population of 434 cirque-like alcoves, we observe a south to southeast bias with an average of 153.09° (Fig. 6). The southeast bias becomes stronger in the normalized rose diagram of aspect (Fig. 6b). The largest binned median sizes, defined as , and areas for cirque-like alcoves are located at lower latitudes (Fig. 7a). Most of the largest binned median sizes and areas of cirque-like alcoves have slopes of 20–25° (Fig. 7b), and cirque-like alcoves have an average slope of ∼ 21.1°. The binned median size and area of the cirque-like alcoves increase with elevation (Fig. 7c). Above 46° in latitude, most cirque-like alcoves cluster between 100–275° in aspect (Fig. 8a). We also notice a lower density of cirque-like alcoves facing 250–360° at all latitudes (Fig. 8a). Cirque-like alcove elevation decreases as latitude increases (Fig. 8b). Similarly, cirque-like alcove height also decreases as latitude increases (Fig. 8c).

Figure 7Cirque-like alcove size and area vs. (a) latitude, (b) slope, and (c) elevation for only cirque-like alcoves in Deuteronilus Mensae. Medians are displayed as black bars for each interval.

4.2 Comparison between cirque-like alcoves and glacier-like forms mapped in Deuteronilus Mensae

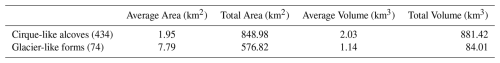

Both the largest cirque-like alcoves and glacier-like forms are located in the southeast part of the study region (Fig. 3). ∼ 70 % of all cirque-like alcoves are within 10 km of a glacier-like form. By comparing the measurements of glacier-like forms (Brough et al., 2019) with cirque-like alcoves, we find that while the average area of an alcove is smaller than a glacier-like form, the total area of all the cirque-like alcoves is larger than the total area of the glacier-like forms (Table 4). There are 74 mapped glacier-like forms in Deuteronilus Mensae (Brough et al., 2019), which is only about 16 % of the total 434 cirque-like alcoves in this study area. As a result, the aggregate total area and aggregate total volume for the cirque-like alcoves are larger than for the glacier-like forms in this study area. In addition, the average cavity volume of an alcove is larger than the volume of a glacier-like form because the cirque-like alcoves have a greater height than the typical estimated thickness of a glacier-like form.

Table 4Area and volume statistics of cirque-like alcoves versus glacier-like forms. Area and volume for glacier-like forms are found by Brough et al. (2019), where glacier-like form volume, including both debris and ice, is calculated using a volume-area scaling approach. Statistics for the cirque-like alcoves come from the topographic cavity of the alcove. We use total cavity volume as an approximation here, though cirque-like alcoves in their present state are not completely full of ice.

Figure 9(a) Bar plots of the aspect compared to the quantity of both cirque-like alcoves and glacier-like forms. (b) Bar plots of the aspect compared to the average volume in each aspect direction for both cirque-like alcoves and glacier-like forms.

While the highest percentage (22 %) of glacier-like forms have a northeast orientation (based on data from Brough et al., 2019), the highest percentage (20 %) of cirque-like alcoves have a southward orientation (Fig. 9a). For both glacier-like forms and cirque-like alcoves, the west and northwest aspects have relatively low numbers ranging from 2 % to 9 % of the entire population, though unlike glacier-like forms (15 %), cirque-like alcoves also have a low proportion of 7 % for the north-facing aspect. For mean glacier-like form volume grouped by aspect, the largest glacier-like forms face southwards in Deuteronilus Mensae, whereas the largest cirque-like alcoves by volume face the north (Fig. 9b).

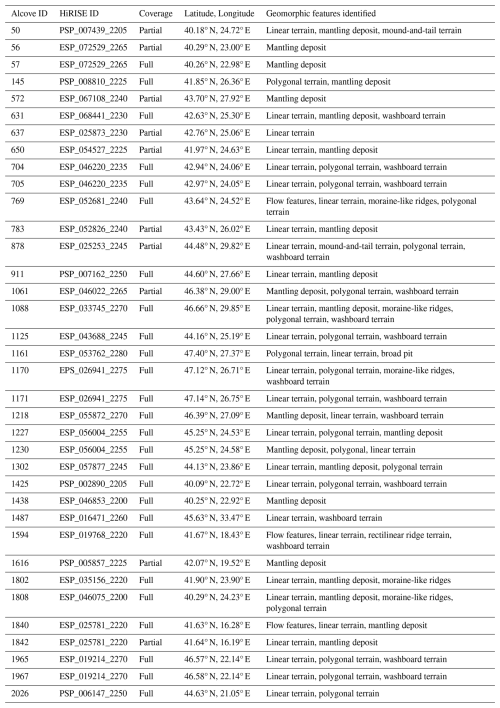

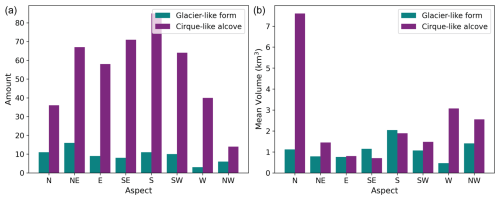

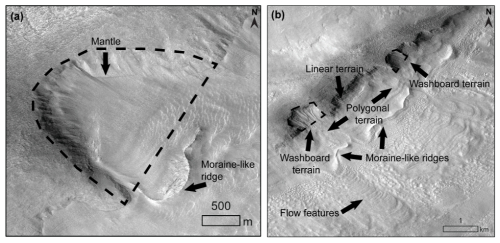

4.3 Geomorphic evidence for past glacial occupation of cirque-like alcoves

In addition to morphometric observations, we identified geomorphic features in association with the cirque-like alcoves that are consistent with either past, remnant, or active ice in order to evaluate aspects of the glacial history in the cirque-like alcoves. Using the criteria stated in Table 3, we identified flow features, linear terrain, mantling deposit, moraine-like ridges, mound-and-tail terrain, polygonal terrain, rectilinear-ridge terrain, and washboard terrain in available HiRISE imagery (specific HiRISE frames are listed in Appendix B). Out of 434 cirque-like alcoves, there was complete overlap in available HiRISE frames with 26 cirque-like alcoves (8 %) and partial overlap with only 10 cirque-like alcoves (1 %). For both HiRISE and CTX imagery, the linear terrain and mantling deposit were the two most common features. We provide the percentages of each feature in both HiRISE and CTX imagery in Table 5.

Table 5Percent of HiRISE and CTX images with each type of geomorphic feature associated with past glacial occupation of cirque-like alcoves. We also include here the mantling deposit, an ice-rich unit. “N/A” in the third column means the CTX images have too low of a resolution to identify the feature.

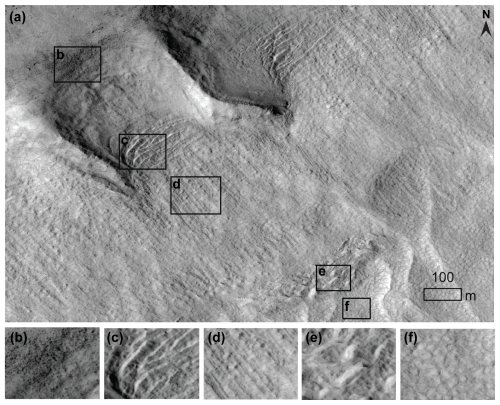

Figure 10(a) Cirque-like alcove with evidence for remnant ice centered at 46.57° N, 22.12° E in HiRISE image ESP_019214_2270_RED. (b) Boulders near the top of the headwall indicating erosion. Features corresponding to ice-loss include the following: (c) washboard terrain (Jawin and Head, 2021), (d) linear terrain, (e) rectilinear ridges (Hubbard et al., 2011), and (f) polygonal terrain. (e.g., Hubbard et al., 2011).

Figure 11Examples of geomorphic features corresponding to past glacial occupation of alcoves. Alcoves identified as cirque-like alcoves are denoted with black dashed lines on oblique HiRISE images. (a) Potential icy form with a clear moraine-like ridge observed in a cirque-like alcove. HiRISE image ESP_033745_2270_RED is centered at 46.64° N, 29.83° E. (b) Possible unconstrained (known as piedmont) glaciation and moraine-like ridges. Linear terrain, washboard terrain features, and polygonal terrain are all present, though not all alcoves are cirque-like (as previously defined in Sect. 3). Washboard terrain is constrained within the base of the alcoves, while polygonal terrain is just downslope of it and more extensive. HiRISE image ESP_026941_2275 is centered at 47.09° N, 26.74° E. HiRISE data credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona.

Figure 10 provides examples of washboard terrain, linear terrain, rectilinear ridges, and polygonal terrain, which all correspond to either the presence of ice or past presence of ice and processes of ice loss, as described in Table 3. The linear terrain extends out from the washboard terrain at the base of the cirque-like alcoves (Fig. 10). The rectilinear ridges are downslope of both the washboard terrain and linear terrain. The polygonal terrain is between the two sections of linear terrain (Fig. 10). In addition, the polygonal terrain is observed farther downslope of the rectilinear ridges (Fig. 10).

Approximately 14 % of cirque-like alcoves with HiRISE imagery coverage have moraine-like ridges. Figure 11 contains examples of moraine-like ridges. Figure 11b also shows additional examples of moraine-like ridges downslope of alcoves (that are not all cirque-like), with along-flow linear terrain between the alcove headwall and the moraine-like ridge. As in Fig. 10, washboard terrain, linear terrain, and polygonal terrain are all present. In addition, flow features are also present in Fig. 11b.

5.1 Geologic context of morphometrics

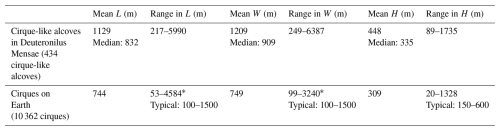

5.1.1 Comparison of length, width, and height of cirque-like alcoves on Mars with cirques on Earth

We further evaluate whether cirque-like alcoves are indeed cirques by comparing them to cirques on Earth. Table 6 compares the length, width, and height for the cirque-like alcoves in Deuteronilus Mensae (as defined by morphometrics and the simple alcove class in Sect. 3.2.2) to a global population of 10 362 cirques on Earth as compiled in a review by Barr and Spagnolo (2015). Like cirques on Earth, both length and width are on average over twice the value of height for cirque-like alcoves (Table 6). On average, cirque-like alcoves have length, width, and height values that are larger than cirques on Earth.

Table 6A comparison of the length (L), width (W), and height (H) for cirque-like alcoves mapped in this study in Deuteronilus Mensae, Mars, and a population of 10 362 cirques on Earth (Barr and Spagnolo, 2015).

* Both 4584 m for the maximum length and 3240 m for the maximum width are specific to cirques in the Dry Valleys of Antarctica (Aniya and Welch, 1981).

The median cirque-like alcove size () in Deuteronilus Mensae is ∼ 11 % larger than the average cirque on Earth. This suggests that compared to Earth, the cirque-like alcoves in Deuteronilus Mensae on Mars may have formed due to more (or more frequent) glaciation events, longer-lasting glaciation, larger initial hollows for snow accumulation, faster glacial erosion rates (though this is considered unlikely; see Table 7), or a combination of these factors. Future modeling may better investigate which is the most likely cause.

5.1.2 Trends in aspect for cirque-like alcoves and implications for cirque initiation

The eastward bias for cirque-like alcove aspect is similar to the trend of cirques in the mid-latitudes on Earth, where cirque aspect commonly faces eastward because glaciers are more likely to grow on the lee side of slopes crossed by westerly winds present at these latitudes (Barr and Spagnolo, 2015). This is consistent with climate modeling on Mars, which shows that both westerly winds and ice deposition are expected in Deuteronilus Mensae during the northern winter under higher obliquity (Madeleine et al., 2009). Similar to cirque-like alcoves in Deuteronilus Mensae, the glacier-like form population in the northern hemisphere also has an eastward bias (Souness et al., 2012).

The southern bias is less intuitive. Cirques on Earth are generally biased toward having a poleward-facing orientation, where total solar radiation is lowest and lower air temperatures allow for glaciers to persist for longer (Barr and Spagnolo, 2015). To explain the southward bias of cirque-like alcoves in the northern mid-latitudes of Mars, we propose that this is consistent with periods of higher obliquity >45° on Mars, when poleward-facing slopes received higher insolation and summer day temperatures, and equator-facing slopes received relatively less insolation (Costard et al., 2002; Kreslavsky et al., 2008). As a result, during periods of high obliquity, equator-facing cirque-like alcoves in the northern mid-latitudes would have been more favorable for ice accumulation. For regions poleward of 40° like in Deuteronilus Mensae, gullies are also primarily observed on equator-facing slopes (Harrison et al., 2015; Conway et al., 2018). This is possibly due to the melting of near-surface ground ice during periods of high obliquity (Costard et al., 2002), though the exact formation mechanism of gullies remains unclear (e.g., Conway et al., 2018; Dundas et al., 2022). For Deuteronilus Mensae, the average aspect within gullies is 180.51°, though north-facing gullies are also common (Noblet et al., 2024). Meltwater generation is more commonly invoked for the formation of older, inactive gullies during periods of higher obliquity (e.g., Dickson et al., 2023; Noblet et al., 2024). On the other hand, gullies that have been observed to be recently active invoke CO2 frost, as well as dry mass wasting during frost-free seasons (e.g., Dundas et al., 2022), though melting within dusty H2O ice remains a possibility too (e.g., Khuller et al., 2021).

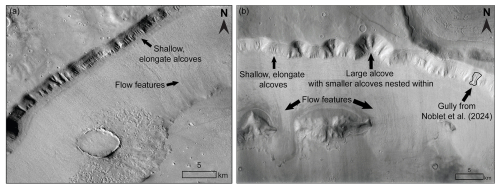

Figure 12Examples of mesa slopes with shallow alcoves, larger alcoves, and adjacent ice. (a) Shallow alcoves may indicate ice-associated erosion all along the mesa sidewall. Flow features indicate the downslope direction of ice flow. Centered at 41.06° N, 17.88° E in CTX image D04_0288880_2193_XI_39N342W. (b) Shallow alcoves may indicate ice-associated erosion while larger alcoves with multiple smaller alcoves nested within may represent a later stage of development. Gullies (Noblet et al., 2024) may also act as initiation points for alcoves. Flow features indicate the downslope direction of ice flow. While the larger alcoves in this figure were mapped as alcoves, they were not classified as simple alcoves (and as a result, not cirque-like alcoves) because they have interior ridges (Appendix A). Centered at 40.02° N, 23.20° E in the CTX mosaic (Dickson et al., 2018). HiRISE data credit: NASA/JPL/University of Arizona. CTX data credit: Caltech/NASA/JPL/MSSS.

Shallow elongate alcoves exist on hillslopes adjacent to larger alcoves (Fig. 12). These shallow, elongate alcoves are not necessarily gullies according to the narrow morphological definition of Martian gullies in the literature (e.g., Conway et al., 2018), though gullies do exist alongside alcoves as well (Fig. 12b). Regardless of how shallow alcoves of any kind are initiated (be they gullies or other types of hillslope depressions), they may act as cold traps where snow could accumulate (e.g., Dickson et al., 2023) and initiate formation of cirque-like alcoves. For example, shallow alcoves and gullies could provide the initial concavity for a later cirque-like alcove to develop when glaciation occurs (Fig. 12), which is consistent with gully heads that have been proposed as initiation points for cirques on Earth (Derbyshire and Evans, 1976). In turn, deglaciation may also prime the landscape by exposing unconsolidated sediment for later gullying (e.g., Jawin and Head, 2021). Figure 12a provides examples of shallow alcoves incised along the mesa slope. Figure 12b includes both similar shallow, elongate alcoves, as well as gullies identified by Noblet et al. (2024) alongside larger alcoves with multiple channels. The shallow alcoves in Fig. 12a may indicate initial erosion of the mesa sidewall, while the larger alcoves in Fig. 12b may represent later stages of alcove development. Flow features indicate downslope flow of ice away from the mesa sidewalls. While outside the scope of this study, additional analyses are necessary to evaluate this potential cycle of whether shallow alcoves or even gullies could create initiation points for cirque-like alcove formation while deglaciation acts to prime the landscape for later gullying. Future work is necessary to elucidate this potential cyclical relationship of repeated ice accumulation on the landscape, including the possible role of past melting.

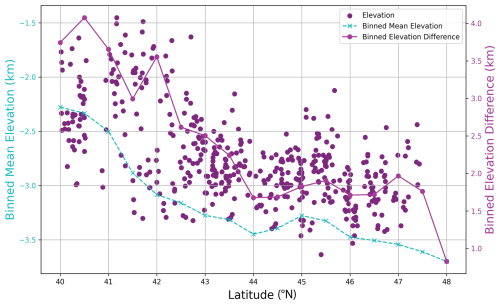

Figure 13Scatterplot of mean elevation for the 434 cirque-like alcoves versus latitude (magenta points). The magenta solid line and teal dashed line are binned from 41 618 659 elevation scatter points from the mosaicked HRSC DEM, which were found using the raster to point tool in ArcGIS Pro. The binned mean elevation (magenta line) represents the mean elevation value of all the HRSC DEM scatter points rounded to each half degree of latitude in the study region. The binned elevation difference (teal dashed line) was calculated based on the difference between the mean of the highest 10 000 points and the mean of the lowest 10 000 points rounded to each half degree of latitude.

5.1.3 Trends between size, area, latitude, slope, and elevation

Relationships between size, area, latitude, mean elevation, and height of the cirque-like alcoves (Figs. 7–8) are likely affected by the nature of the topography in this region. The mean elevation of cirque-like alcoves in Deuteronilus Mensae decreases toward the north (Fig. 13). At lower latitudes, the mesas are at a higher elevation relative to the basin than at higher latitudes (Figs. 3, 13). These two factors combined mean that at lower latitudes, the cirque-like alcoves have a higher mean value for elevation and height due to the topography. Since size is calculated as , the larger height at the lower latitudes corresponds to a larger cirque-like alcove size. Height also scales with length and width for cirque-like alcoves (Sect. 4.1), which is why both larger sizes and areas of cirque-like alcoves correspond to lower latitudes (Fig. 7b). Thus, the local elevation and local mesa height limit the local cirque-like alcove height at different latitudes in Deuteronilus Mensae.

5.1.4 Comparison between cirque-like alcoves and glacier-like forms mapped in Deuteronilus Mensae

Glacier-like forms are mostly pole-facing in Deuteronilus Mensae (Souness et al., 2012), which corresponds to present-day conditions that are favorable for ice preservation. This may indicate that cirque-like alcoves were generated during an earlier phase of glaciation before the glacier-like forms or this may be due to preservation bias as poleward-facing glacier-like forms may have outlasted other directions. If cirque-like alcoves do in fact correspond to an earlier phase of glaciation, it is unclear if this glaciation was on the scale of glacier-like forms versus larger scales like the lobate debris apron, though the timescale for each would require different erosion rates (Sect. 5.3). It is also possible that cirque glaciers in the cirque-like alcoves eventually connected with larger ice bodies like the lobate debris apron and lineated valley fill.

Even though most glacier-like forms face the pole, the glacier-like forms with the largest volume face southwards in Deuteronilus Mensae (Souness et al., 2012; Fig. 9). This may be due to a localized topographic effect for glacier-like forms in Deuteronilus Mensae because overall for the northern hemisphere, glacier-like forms flowing northward are larger than those flowing southward by about 20 % (Brough et al., 2019). The largest cirque-like alcoves by volume face north and west, which may be due to topographic effects as well, since by number, more cirque-like alcoves face south. For both glacier-like forms and cirque-like alcoves, the aspect with the highest proportion of the regional population does not correspond to the aspect with the largest mean volume (Fig. 9).

Since both the largest cirque-like alcoves and glacier-like forms are located in southeast Deuteronilus Mensae, this may indicate that there is a local factor impacting both glacier-like form size and cirque-like alcove size or that the two are linked in how they form. For the first option, this may be because of local topography that enhances the conditions for precipitation and snow accumulation. If we assume that the cirque-like alcoves were eroded by the same phase of glaciation as the glacier-like forms, then the cirque-like alcoves may now be empty of glacier-like forms because their preservation became unfavorable in current obliquity conditions. In that case, conditions in the southeast of this region resulted in both the largest glacier-like forms and cirque-like alcoves. If we instead assume that all cirque-like alcoves had reached most of their current size before the glaciation cycle that brought the glacier-like forms, then the growth of glacier-like forms may be slowed depending on the initial size of the cirque-like alcove that it occupies. While we do not distinguish between these hypotheses in this study, we recommend future work to investigate the direct cause of the larger glacier-like forms and cirque-like alcoves in the southeast part of Deuteronilus Mensae.

Overall, the average glacier-like form has a larger area than the average cirque-like alcove because glacier-like forms typically extend beyond the cirque-like alcoves that they emerge from. Although the average area of a cirque-like alcove is smaller than a glacier-like form, the total area of all the cirque-like alcoves is larger than the total area of the mapped glacier-like forms in our study area (Table 4). If the simple cirque-like alcoves that we identify here are in fact representative of glacial erosion, then we extend our previous knowledge of the areal extent of past glaciation in Deuteronilus Mensae.

5.2 Geomorphic interpretations of cirque-like alcoves and associated geomorphic features

We find that 42 % of available HiRISE images contained washboard terrain, while only 2 % of CTX images did, though this is likely due to a resolution issue since finer textures cannot be resolved at CTX scale. Other than two exceptions, cirque-like alcoves that contained washboard terrain did not also have an identifiable mantling unit. Similar to its presence at the bottom of crater walls (Jawin et al., 2018; Jawin and Head, 2021), the presence of washboard terrain here at the bottoms of the mesa sidewalls indicates deglaciation.

In both HiRISE (81 %) and CTX imagery (57 %), a high percentage of images of cirque-like alcoves contained observable linear terrain. In Fig. 10, since the linear terrain extended out from the washboard terrain, which is due to surficial crevasses, this suggests that the linear terrain there may be most similar to supraglacial longitudinal foliation (Table 3). However, linear terrain could still result from subglacial erosion despite superposing a mantling unit since a mantling unit consists of layers of dust and snow that build up in the latitude dependent mantle over multiple obliquity cycles (e.g., Khuller et al., 2021). Applied here, this would imply that the ridges could have been subglacially eroded, but from another layer of ice of the mantling unit (compacted from dust and snow) that formerly existed on top of the rest of what is left of the mantling unit today.

As with moraines on Earth, the position of the moraine-like ridges on Mars reveal the extent of glaciation relative to the cirque-like alcoves. Moraine-like ridges extend either directly from (Fig. 11a) or downslope of cirque-like alcoves (e.g., Figs. 11b, 5). The moraine-like ridges that extend directly from cirque-like alcoves (Fig. 11a) are akin to terminal moraines formed by terrestrial cirque glaciers that only remain within their cirque basin. Moraine-like ridges farther downslope (Fig. 5) reflect a stage where the glaciers grew beyond the cirque-like alcoves.

Similar to Arfstrom and Hartmann (2005), the moraine-like ridges in Fig. 11b reflect the glacial erosion and deposition of mesa material sourced from their corresponding upslope alcoves. In Fig. 11b, only two of the alcoves are well-developed and have morphometrics corresponding to the criteria we set for cirque-like alcoves. The rest of the alcoves remain underdeveloped and require further glacial erosion to qualify as cirque-like alcoves.

5.3 Estimating the timescales for cirque-like alcove erosion on Mars

From terrestrial studies we know that cirques are formed by glacial erosion, which generally requires liquid water at the base of a wet-based glacier (Glasser and Bennett, 2004). On the other hand, cold-based glaciers on Earth are minimally erosive (Table 7) and are therefore not typically associated with large-scale glacial erosion features such as glacial valleys, troughs or cirques. However, it cannot be excluded that minimally erosive cold-based glaciers that operate over orders of magnitude longer timescales than a few glaciation cycles may still contribute to the erosion of large features. For example, measurements at cold-based Meserve Glacier in Antarctica find an erosion rate of to m yr−1 (Cuffey et al. 2000), meaning that assuming a constant erosion rate, it would take 100–330 million years of continuous glacial erosion to produce a 300 m deep cirque on Earth. In locations such as the Dry Valleys of Antarctica where cold-based glaciers currently reside within cirques, it is likely that much of the erosion of the cirque occurred during an earlier more temperate phase of glaciation during the Miocene (e.g., Selby and Wilson, 1971; Sugden and Denton, 2004; Clinger et al., 2020). If these Martian cirque-like alcoves are analogous to terrestrial glacial cirques, then they may have formed either during an earlier wet-based phase at the scale of an active glacier-like form, or formed during a prior cold-based glacial cycle separate from the glacier-like forms, such as when lobate debris aprons formed.

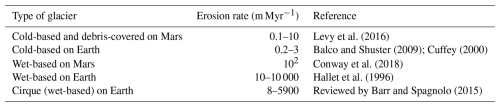

Table 7Comparison of published erosion rates for cold-based glaciers, wet-based glaciers, and glacial cirques (wet-based) on Earth.

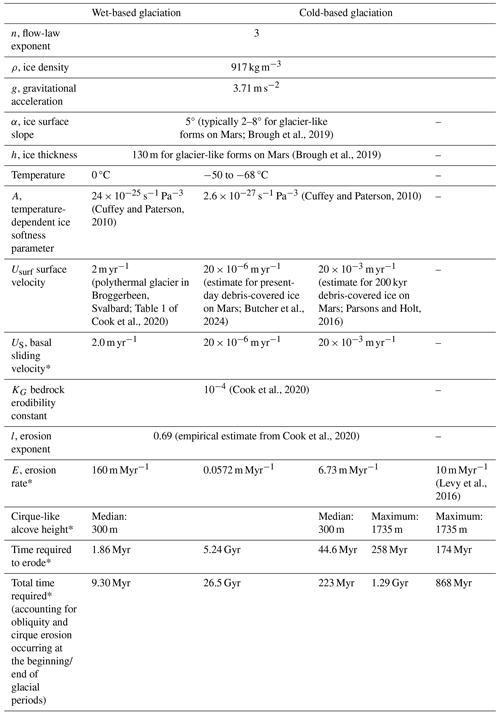

Using terrestrial understanding of glacier erosion we can calculate approximately how long the glacial erosion of a median cirque-like alcove would take based on different assumptions. First, we take into account that the surface gravity of Mars is about one third of Earth's at 3.71 m s−2. Second, in order to calculate erosion rates in the past we estimate the former ice-surface velocity to derive the basal sliding velocity, keeping in mind that sliding velocities are notably higher for wet-based glaciers than for cold-based glaciers. Third, we estimate the total occupation time of active (flowing) glaciers in the cirque-like alcoves, which on Mars is likely a function of orbital forcing (e.g., Laskar et al., 2002). We estimated erosion rates for both wet- and cold-based ice. From the calculations below, our estimated erosion rates indicate that a cold-based glacier would take an order of magnitude longer than a wet-based glacier to erode the cirque-like alcoves, and that our estimates are consistent with previous estimates of erosion rates (Levy et al., 2016; Conway et al., 2018) and timescales of past episodes of glaciation on Mars (Berman et al., 2015; Hepburn et al., 2020).

Our erosion rate estimates are derived from basal sliding velocities (US) which are in turn derived from glacier surface velocities, using an empirical relationship from a terrestrial global dataset of 38 glaciers (Cook et al., 2020):

where A is a temperature-dependent ice softness parameter (for warm ice at 0 °C, ; for cold ice at −50 °C, ; Cuffey and Paterson, 2010), n is a flow-law exponent that is typically 3, ρ is ice density, g is gravitational acceleration, α is ice surface slope, h is ice thickness, and Usurf is glacier surface velocity. For the A parameter, since it is unknown how much the temperature of ice on Mars has fluctuated throughout the Amazonian, we use both a warm and cold ice scenario. For the warm ice, we use 0 °C (Table 8). For the cold ice, −50 °C is the coldest temperature for A from Cuffey and Paterson (2010) that approaches the mean annual present-day surface temperature of −63 °C (e.g., Forget et al., 1999; Butcher et al., 2024). As an example of a type of glacier that may have occupied and eroded cirque-like alcoves on Mars, we use values from glacier-like forms. For glacier-like forms on Mars, average h is 130 m and, since α ranges from 2 to 8° (Brough et al., 2019), we use 5° here to represent an order-of-magnitude estimate. For finding Usurf, surface velocities of glacier-like forms on Mars are not well constrained and may have included short, warm periods that allowed for melting (Hubbard et al., 2014). For a lower bound surface velocity for cold-based glaciers on Mars, recent modeling using a mean annual present-day surface temperature of −63 °C and found a maximum surface velocity of m yr−1 for a thin (<100 m) viscous flow feature on a steep slope (Butcher et al., 2024). On the other hand, Parsons and Holt (2016) find surface velocities ranging from 0.05–20 mm yr−1 for ice at −68 °C, with the lower velocity of 0.05 mm yr−1 corresponding to 200 Myr ice and 20 mm yr−1 corresponding to 200 kyr ice. We include 20 mm yr−1 as an upper bound for cold-based surface velocity (Table 8). For the wet-based case, we use a surface velocity of 2 m yr−1 (based on a polythermal glacier in Broggerbeen, Svalbard; Table 1 of Cook et al., 2020). Erosion rate E was calculated as:

where KG is a bedrock erodibility constant and l is an erosion exponent. While KG and l can vary depending on the bedrock type, KG is commonly 10−4 (Cook et al., 2020). Cook et al. (2020) empirically estimated l to be 0.69 based on the relationship between the erosion rate and glacier sliding velocity of 38 glaciers, including Meserve Glacier, and we use that value in our estimates.

While this study does not provide exact age constraints for cirque-like alcoves, our erosion rate estimates help constrain the minimum length of time required for their development. For the wet-based glaciation scenario, we estimate an erosion rate of ∼ 160 m Myr−1, which is close to the upper end of the 0.08 to 181 m Myr−1 range estimated by Conway et al. (2018) for glaciated crater walls on Mars. To estimate the amount of time necessary to erode a cirque-like alcove, we divide the erosion rate by the median height of a cirque-like alcove of 335 m, rounded down to 300 m. While an overestimate, similar to the estimation of volume (as described in Sect. 3.2.2), we use the height as a proxy for the maximum amount of material that could have been eroded from a cirque-like alcove. For continuous glacial occupation and ignoring that glaciers may have only been active (and eroding their bed) during specific obliquity periods, this would suggest that a total of ∼ 1.9 Myr would be required for the cirque-like alcoves to form (Table 8). However, accounting for changes in obliquity when the conditions may not have always been optimal for active glaciation would extend this time. As an estimate, over the last 10 Myr, there were 100 kyr orbital cycles, with periods of high obliquity lasting 20–40 kyr (Head et al., 2003). On Earth, cirques are presumed to be mostly eroded at the beginning and the end of glaciations (e.g., Barr et al., 2019), so assuming that the cirque-like alcoves only have 20 kyr of erosion time during every 100 kyr period, or 20 % of the total time passing by, it would take ∼ 9.3 Myr of total time to erode a median height cirque-like alcove using wet-based glacial erosion rates (Table 8). This timescale is consistent with previous estimates of the age of certain populations of glacier-like forms (Hepburn et al., 2020), which means that at least some of the glacier-like forms could have eroded the cirque-like alcoves which they currently occupy if they had wet-based glacial erosion rates and that at least some of the empty cirque-like alcoves could have hosted glaciers in the past tens of millions of years.

Table 8Overview of the constants, values, and results used for age calculations of cirque-like alcoves on Mars. Values that were used for both the wet-based and cold-based calculations are in the middle where there is no header.

“∗”indicates values that were calculated in this work. “–” indicates that the value was not used for that column.

On the other hand, if we assume cold-based conditions for glaciers that occupied the cirque-like alcoves, then the erosion rate estimated is ∼ 0.057 to 6.7 m Myr−1. However, the lower bound of 0.057 m Myr−1 is unrealistically low because a median cirque-like alcove would take longer than the age of Mars to erode (Table 8). However, the upper bound of ∼ 6.7 m Myr−1 falls within the previous wide-ranging estimate of 0.1–10 m Myr−1 for cold-based viscous flow features on Mars (Levy et al., 2016). Using an erosion rate of 6.7 m Myr−1, a total glacier occupation time of ∼ 45 Myr would be required for median cirque-like alcoves to form without accounting for obliquity variations. By including obliquity variations and using an erosion rate of ∼ 6.7 m Myr−1, a median height cirque-like alcove would require ∼ 220 Myr to erode (Table 8). For a maximum height cirque-like alcove, an erosion rate of ∼ 6.7 m Myr−1 would yield a total age of ∼ 1.3 Gyr (Table 8), which is slightly longer than the ∼ 500 Myr (Fassett et al., 2014) to 1.1 Gyr (Berman et al., 2015) timescales of when lobate debris aprons and concentric crater fills were estimated to have formed. If instead the upper-end erosion rate of 10 m Myr−1 for cold-based glaciers is applied from Levy et al. (2016), then all heights of the cirque-like alcoves could have formed via cold-based glacier erosion within ∼ 870 Myr (Table 8).

Since debris extending from the alcoves often superposes the lobate debris aprons (e.g., Baker and Carter, 2019), this means that the process eroding the cirque-like alcoves continues after when the ice in the lobate debris aprons formed. Whether this stage of erosion of the cirque-like alcoves is primary or secondary modification (e.g., via paraglacial mass wasting) is unclear. Similarly, on Earth, the chronology of cirque formation is difficult to constrain (e.g., Turnbull and Davies, 2006), and estimates for total glacial cirque erosion time range from 125 kyr (Larsen and Mangerud, 1981) to a few million years (Andrews and Dugdale, 1971; Anderson, 1978; Sanders et al., 2013).

In summary, our estimates here find that a median height cirque-like alcove in Deuteronilus Mensae would take ∼ 9.3 Myr to form if occupied by a wet-based glacier at 0 °C with an erosion rate of 160 m Myr−1, assuming a slope and an average ice thickness of glacier-like forms on Mars from Brough et al. (2019). For the cold-based case, using a very low surface velocity from Butcher et al. (2024) and present-day temperature of −60 °C yields an unrealistic age for the cirque-like alcoves that is older than the age of Mars. However, if a faster surface velocity is applied from Parsons and Holt (2016), then a median cirque would require ∼ 220 Myr if occupied by a cold-based glacier at −50 to −68 °C with an erosion rate of 6.73 m Myr−1, again assuming a slope and average ice thickness representative of glacier-like forms. Since cold-based erosion rates may vary by up to two orders of magnitude, maximum cold-based erosion rates closer to 10 m Myr−1 would allow for timescales of hundreds of millions of years. Thus, if the glaciers were cold-based during their entire evolution, the erosion timescale is longer and therefore the alcoves must be much older than if they evolved during periods of wet-based glaciation. Whether the cold-based erosion rates on Mars were more similar to what has been observed at Meserve Glacier in Antarctica at ≤3 m Myr−1 (Cuffey et al., 2000) or at much higher values closer to 10 m Myr−1 (Levy et al., 2014) remains unknown.

This is the first in-depth, regional population scale study of the morphometrics and geomorphic evidence of previous ice occupation associated with cirque-like alcoves on Mars, that uses terrestrial knowledge to make a case that a sub-population of the mapped alcoves were likely eroded by past glaciation. By mapping ∼ 2000 alcoves in Deuteronilus Mensae that did not contain previously mapped glacier-like forms, grouping them into six classes, and then downselecting to only simple alcoves with length/width () between 0.5 to 4.25, length/height () of 1.5 to 4.0, and width/height () of 1.5 to 4.0, which are consistent with terrestrial cirques, we are able to identify a regional population of 434 “cirque-like alcoves”. We constrained our dataset to a total of 434 cirque-like alcoves in the study area, where previously only 74 glacier-like forms had been mapped (Brough et al., 2019). Thus, these cirque-like alcoves expand our knowledge about the landscape imprints of formerly more extensive glaciation in Deuteronilus Mensae and potential landscape evolution processes in this region. Using HiRISE imagery that was available for ∼ 9 % of these cirque-like alcoves, we find evidence of associated geomorphic features as evidence for past glacial occupation of cirque-like alcoves, including flow features, linear terrain, moraine-like ridges, mound-and-tail terrain, polygonal terrain, rectilinear-ridge terrain, and washboard terrain, as well as an ice-rich mantling unit (Figs. 11–12). All of these features have been found in association with glacier-like forms in previous work (e.g., Arfstrom and Hartmann, 2005; Morgan et al., 2009; Hubbard et al., 2011; Hubbard et al., 2014). This data analysis leads us to draw the following conclusions:

-

434 alcoves in Deuteronilus Mensae are morphometrically consistent with origins as glacially-eroded cirques.

-

Cirque-like alcoves contain geomorphic features consistent with a glacial origin, as signified by the presence of flow features, linear terrain, washboard terrain, rectilinear-ridge terrain, moraine-like ridges, and polygonal terrain, as well as the ice-rich mantling unit (Sect. 4.3). While these icy deposits do not have all of the criteria to correspond to glacier-like forms, the features in many cirque-like alcoves represent a continuum of ice evolution, potentially as ice in viscous flow features such as glacier-like forms degrade and contain less ice volume.

-

The cirque-like alcoves in Deuteronilus Mensae have a median size ∼ 11 % larger than the average size of cirques on Earth (Sect. 5.1), which may suggest that cirques in Deuteronilus Mensae underwent more or longer episodes of erosive glaciation than cirques on Earth. The largest cirques are in the lower latitudes of the study region at 40–42.9° N (Fig. 7a). This is likely the result of local topography because the local mesa height at different latitudes may limit local cirque-like alcove height and size (Sect. 5.1.3).

-

There is a dominant southeastward bias in the aspect of the cirque-like alcoves (Fig. 6), which becomes more pronounced above 44° N (Fig. 8). The southward component likely suggests cirque-like alcoves formed during a period of high obliquity when conditions were more favorable for glacier growth at these latitudes as poleward-facing slopes received higher insolation and warmer summer daytime temperatures than equator-facing slopes (Sect. 5.1.2). Similarly, cirque-like alcove formation may be linked to gully formation since gullies also preferentially face the equator for slopes poleward of 40° (Harrison et al., 2015; Conway et al., 2018). Overall, both cirque-like alcoves and glacier-like forms tend to have greater volumes when facing south, which may suggest a relationship between glacier-like form size and cirque-like alcove size. In addition to a southward bias, an eastward bias in aspect aligns with previous studies of both glacier-like forms on Mars (e.g., Souness et al., 2012; Brough et al., 2019) and climate models of westerly winds in Deuteronilus Mensae (Madeleine et al., 2009). Terrestrial cirques also show a similar pattern due to westerly winds. Future work could help to better understand the atmospheric controls on cirque-like alcove formation in Deuteronilus Mensae, as well as other locations on Mars.

-

Shallow, elongate alcoves (similar to gullies) and gullies are observed adjacent to increasing sizes of larger alcoves (Fig. 12). Shallow, elongate alcoves and subsequent stages of their development may act as initiation points for ice accumulation, similar to what happens on Earth for local-slope glaciation. Larger alcoves may have undergone multiple cycles of glaciation and erosion. This process is consistent with previous work by Jawin et al. (2018).

-

We estimate the time required for cirque-like alcove formation in Deuteronilus Mensae using Mars' surface gravity, obliquity models, and assume an ice temperature of 0 °C for a warm-based case, and −50 to −68 °C for cold-based glaciers (Sect. 5.3). Assuming a wet-based glacial erosion rate (∼ 160 m Myr−1), cirque-like alcove formation would take ∼ 9.3 Myr, consistent with age constraints for glacier-like forms. Using a range of surface velocities for cold-based glaciers resulted in erosion rates from 0.057 to 6.7 m Myr−1. Assuming the lower bound for cold-based glacial erosion (∼ 0.057 m Myr−1), median height cirque-like alcove formation would not be achievable within the lifetime of Mars (Table 8). However, cold-based erosion rates on Mars may have been higher in the past, such as 6.7 m Myr−1, or with some estimates reaching ∼ 10 m Myr−1 (Levy et al., 2016), which could reduce formation time for all heights of cirque-like alcoves to ∼ 870 Myr. These estimates are highly dependent upon the past flow velocity chosen, which is poorly constrained for past climate regimes on Mars. Further research is needed to evaluate the potential for cold-based glaciers to erode cirques on Mars, even though this process is minimal on Earth.

Here we show that cirque-like alcoves are consistent with the morphometrics of terrestrial cirques and retain geomorphic features indicative of ice. In addition, cirque-like alcoves have trends in aspect similar to other features such as gullies on Mars. Future work may evaluate additional regions on Mars and further explore the main factors influencing cirque-like alcove development throughout multiple cycles of glaciation and deglaciation. While we bring forward new evidence and associations using our understanding of geomorphology for Earth and Mars, further work, especially using additional high-resolution imagery and topography that may be available in the future, will be necessary to determine the style and timing of glacial activity on Mars.

We identified six broad classes of alcoves: (a) simple, (b) joined, (c) interiorly ridged, (d) staircase, (e) channel-related, and (f) branching (Fig. A1). However, for the purposes of this paper to assess possible glacial erosion, we only focus on simple alcoves. Descriptions and interpretations of each class are in Table A1. Note that the joined and staircase alcoves were mapped as one alcove. On the other hand, due to their larger scale, branching alcoves that offshoot from the same valley were mapped as individual alcoves. As such, smaller, simple alcoves that offshoot from the main trunk of a branching valley would fall into both classes. ∼ 4 % of the alcoves were classified as two or more types. Channel-related alcoves have channels either adjacent to or directly connected to the alcove headwall, which suggest that an erosional mechanism related to liquid water–rather than glaciation–dominated their formation.

The ACME2 tool is designed for classic cirques on Earth and while the tool works with complex shapes, it should not be relied on for curving, elongated features (Spagnolo et al., 2017). As a result, we do not apply ACME2 for all alcove classifications. For the classes including compound, joined, staircase, and branching, the way that each class of alcoves was mapped would affect the subsequent morphometric values. For example, while we mapped branching alcoves as separate alcoves, it is possible that they should instead be considered as one large alcove if the development of individual alcoves are all dependent on the main trunk. This has a significant impact on how morphometrics would be reported because not only will the length greatly vary, but other morphometrics like the aspect will also differ across different alcoves branching off the same trunk. As a result, there is subjectivity introduced from the mapping decisions that subsequently affect evaluations of each alcove class relative to each other. Thus, we do not report on the morphometrics of all classes.

Figure A1Our classification of these alcoves assigns six classes. For each alcove class, panels (i) on the left correspond to an image example, and panels (ii) on the right correspond to an example of the profile. (a) Simple: characterized by its armchair shape, a defined headwall, two sidewalls, and an opening downslope (40.24° N, 34.48° E). (b) Joined: two simple alcoves adjacent to one another that join together downslope (37.72° N, 20.35° E). (c) Interiorly ridged: An alcove that has ridges within it rather than a clean headwall (44.62° N, 24.95° E). (d) Staircase: A simple alcove that has a step up to another simple alcove (37.62° N, 19.59° E). (e) Channel-related: a channel is either immediately adjacent to or directly connected to this alcove's headwall (42.34° N, 18.30° E). (f) Branching: a large alcove valley that is much longer than it is wide with multiple offshoots, including but not limited to smaller simple alcoves (37.97° N, 19.58° E). All images use the CTX mosaic (Dickson et al., 2018) overlaid on mosaicked HRSC (Neukum and Jaumann, 2004) DEM data. HRSC elevation values are included in the elevation profiles. Arrows all point downslope. CTX data credit: Caltech/NASA/JPL/MSSS. HRSC data credit: ESA/DLR/FU Berlin.

The shapefiles, spreadsheet, and corresponding table of column descriptions for the 434 cirque-like alcoves are available at: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17527279 (Li et al., 2025). The mosaicked HRSC DEM is also provided at the same link and was mosaicked using the following 29 Level 4 HRSC data frames: h5436_0000_da4, h5418_0000_da4, h5400_0000_da4, h5364_0000_da4, h5339_0000_da4, h5328_0000_da4, h5321_0000_da4, h5310_0000_da4, h5303_0000_da4, h5285_0000_da4, h5267_0000_da4, h5249_0000_da4, h5231_0000_da4, h5213_0000_da4, h3304_0000_da4, h3293_0000_da4, h3249_0000_da4, h3183_0000_da4, h2191_0000_da4, h1644_0000_da4, h1622_0000_da4, h1571_0000_da4, h1289_0000_da4, h1395_0000_da4, h1461_0000_da4, h1450_0000_da4, h1428_0000_da4, h1483_0000_da4, and h1201_0000_da4. The Level 4 HRSC data frames can be accessed at the ESA Planetary Science Archive: http://www.rssd.esa.int/index.php?project=PSA (last access: 20 August 2025), HRSCview by FU Berlin/DLR: http://hrscview.fu-berlin.de/ (last access: 20 August 2025), or the NASA Planetary Data Science (PDS) http://pds-geosciences.wustl.edu/missions/mars_express/ (last access: 20 August 2025). This paper was prepared using the beta01 CTX mosaic: https://murray-lab.caltech.edu/CTX/beta01.html (Dickson et al., 2018). HiRISE frames were accessed from the University of Arizona's HiRISE website: https://www.uahirise.org/hiwish/browse (last access: 20 August 2025). The HiRISE frames that we examined for geomorphic features included the following: ESP_041934_2265, ESP_040853_2275, ESP_036844_2225, ESP_036580_2260, ESP_036514_2210, ESP_026941_2275, ESP_025873_2230, ESP_025781_2220, ESP_025477_2280, ESP_025253_2245, ESP_023618_2270, ESP_023605_2205, ESP_019768_2220, ESP_019214_2270, ESP_016748_2255, ESP_016471_2260, ESP_016247_2270, ESP_016194_2260, ESP_067108_2240, ESP_060013_2250, ESP_057877_2245, ESP_056004_2255, ESP_055872_2270, ESP_055661_2230, ESP_054527_2225, ESP_053762_2280, ESP_052826_2240, ESP_052681_2240, ESP_052417_2220, ESP_050558_2245, ESP_048949_2230, ESP_046853_2200, ESP_046220_2235, ESP_046075_2200, ESP_046022_2265, ESP_043688_2245, ESP_025319_2240, ESP_016959_2240, ESP_027574_2245, ESP_035011_2240, PSP_006147_2250, ESP_068441_2230, ESP_033745_2270, ESP_035156_2220, and ESP_028418_2240. New CTX DEMs (although not included in the final version of this manuscript) are available from Mackenzie Day's GALE lab at UCLA by request and are publicly accessible here: https://github.com/GALE-Lab/Mars_DEMs (last access: 14 October 2023) and Day et al. (2023).

Project conceptualization by MRK and AYL with funding obtained by MRK. Methodology development by AYL, MRK, and SB. Mapping, classification, initial analyses, and figures were created by AYL. All authors contributed to discussions of the interpretations. All authors also revised and approved the submitted manuscript.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher’s note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. While Copernicus Publications makes every effort to include appropriate place names, the final responsibility lies with the authors. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This article is part of the special issue “Planetary landscapes, landforms, and their analogues”. It is not associated with a conference.

We are grateful to Yingkui Li for taking the time to help us apply ACME 2 to datasets for Mars. We thank Anjali Manoj for her work on alcove classifications. We appreciate that Mackenzie Day and the GALE lab at UCLA provided relevant CTX DEMs. The reviewers Susan Conway, Joseph Levy, and Rishitosh Sinha, as well as the editor Frances Butcher, have contributed comments that immensely improved this manuscript.

This research has been supported by NASA (grant no. 80NSSC20KO747).

This paper was edited by Frances E. G. Butcher and reviewed by Joseph Levy, Rishitosh Sinha, and Susan Conway.

Anderson, L. W.: Cirque glacier erosion rates and characteristics of Neoglacial tills, Pangnirtung Fiord area, Baffin Island, NWT, Canada, Arct. Alp. Res., 10, 749–760, 1978.

Andrews, J. T. and Dugdale, R. E.: Late Quaternary glacial and climatic history of northern Cumberland Peninsula, Baffin Island, NWT, Canada. Part V: factors affecting corrie glacierization in Okoa Bay. Quat. Res., 1, 532–551, 1971.

Aniya, M. and Welch, R.: Morphometric analyses of Antarctic cirques from photogrammetric measurements, Geogr. Ann. Ser. A Phys. Geogr., 63, 41–53, 1981.

Arfstrom, J. and Hartmann, W. K.: Martian flow features, moraine-like ridges, and gullies: Terrestrial analogs and interrelationships, Icarus, 174, 321–335, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2004.05.026, 2005.

Baker, D. M. and Carter, L. M.: Probing supraglacial debris on Mars 1: Sources, thickness, and stratigraphy, Icarus, 319, 745–769, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2018.09.001, 2019.

Baker, D. M. and Head, J. W.: Extensive Middle Amazonian mantling of debris aprons and plains in Deuteronilus Mensae, Mars: Implications for the record of mid-latitude glaciation, Icarus, 260, 269–288, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.icarus.2015.06.036, 2015.

Baker, D. M. H. and Carter, L. M.: Radar reflectors associated with an ice-rich mantle unit in Deuteronilus Mensae, Mars. 48th Annual Lunar and Planetary Science Conference, The Woodlands, Texas, March 2017, No. 1964, p. 1575, https://www.hou.usra.edu/meetings/lpsc2017/pdf/1575.pdf (last access: 20 August 2025), 2017.

Balco, G. and Shuster, D. L.: Production rate of cosmogenic 21Ne in quartz estimated from 10Be, 26Al, and 21Ne concentrations in slowly eroding Antarctic bedrock surfaces, Earth Planet. Sci. Lett., 281, 48–58, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsl.2009.02.006, 2009.

Barlow, J., Franklin, S., and Martin, Y.: High spatial resolution satellite imagery, DEM derivatives, and image segmentation for the detection of mass wasting processes, Photogrammetric Engineering, 72, 687–692, https://doi.org/10.14358/PERS.72.6.687, 2006.