the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Safeguarding Cultural Heritage: Integrating laser scanning, InSAR, vibration monitoring and rockfall/granular flow runout modelling at the Temple of Hatshepsut, Egypt

Mohamed Ismael

Mostafa Ezzy

Markus Keuschnig

Alexander Mendler

Johanna Kieser

Michael Krautblatter

Christian U. Grosse

Hany Helal

The predictive capacity for rockfall has significantly increased in the last decades, but complementary combinations of observation methods accounting for the wide range of processes preparing and triggering rockfall are still challenging, especially at sensitive sites like World Heritage monuments. In this study, we combine Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS), Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR), ambient vibration analyses, and rockfall runout modelling at the 3500-year-old Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, a key World Cultural Heritage Site and among the best-preserved temples in Ancient Thebes, Egypt. The temple is exposed to a 100 m vertical, layered, Eocene Thebes Limestone cliff. Here, a major historic rock slope failure buried the neighbouring temple of Thutmose III, and behind the temple frequent fragmental rockfall occurs. The project “High-Energy Rockfall ImpacT Anticipation in a German-Egyptian cooperation (HERITAGE)” aims to combine TLS and InSAR to constrain pre-failure deformation, potential detachment scenarios, and rockfall runout modelling for singular blocks and granular flows from rock tower collapses towards an integrative analysis. Based on TLS and InSAR, we could measure volumes of small failures between 2022–2023 and map potential detachment zones of interest for larger failures. Only the combination of InSAR and TLS can unequivocally delineate rockfall-active areas without the ambiguity of single techniques. Based on this, we modelled the runout of small single-block failures of the observed size spectrum (0.01–25 m3) and constrained frictional parameters for large (i.e. > 103 m3) granular flows from collapsing towers using historic failures. The applicability of ambient vibration analysis to detect preparatory destabilisation of rock towers prior to deformation by frequency shifts is successfully tested. This study shows the potential of combining non-invasive rockfall observation and modelling techniques for various magnitudes towards an integrative observation approach for cultural heritage such as Egyptian World Heritage Sites. We demonstrate the capabilities of our integrated approach in a challenging hyper-arid climatic, geomorphological and archaeologically sensitive environment, and produce the first event and impact analysis of gravitational mass movements at the Temple of Hatshepsut, providing vital data for future risk assessments.

- Article

(10561 KB) - Full-text XML

-

Supplement

(1341 KB) - BibTeX

- EndNote

Gravitational mass movements pose a threat to cultural heritage sites situated in steep terrain, but their long-term impact on ancient structures has received limited attention. The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut in Deir el-Bahari (Luxor, Egypt) is one of the most prominent archaeological monuments in the region and directly exposed to a ca. 100 m high, jointed limestone cliff. Historic records and archaeological evidence suggest that major slope failures have already impacted the site in the past. However, the current activity state of the rock wall and its hazard potential remain poorly constrained as previous research is limited to the neighbouring Valley of the Kings (Alcaíno-Olivares et al., 2021; Marija et al., 2022), is restrained to the geological past (Dupuis et al., 2011) or focusses more on general risk potential rather than active hazard process monitoring (Abdallah and Helal, 1990; Chudzik et al., 2022; Marija et al., 2022; Ezzy et al., 2025).

Over the past two decades, significant progress has been made in non-invasive geotechnical monitoring techniques that allow for detailed observation of unstable slopes without disturbing sensitive environments. This consideration is especially critical at sensitive World Heritage Sites, where conventional intrusive methods, such as anchors or crack meters, cannot be applied without risk of damaging the site. First, Terrestrial Laser Scanning (TLS) has emerged as a reliable method for high-resolution topographic change detection, especially in inaccessible or protected terrain (Abellán et al., 2014; Hartmeyer et al., 2020a; Shen et al., 2023). It enables precise quantification of surface deformation and erosion rates over time and has been successfully applied in Alpine environments to monitor rockfall activity and retreat rates (Strunden et al., 2015; Mohadjer et al., 2020; Draebing et al., 2022). TLS has also proven suitable for assessing rock tower stability in steep terrain (Santos Delgado et al., 2009; Matasci et al., 2018), a feature characteristic of the cliffs at Deir el-Bahari. Second, Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar (InSAR), particularly with data from Sentinel-1 satellites, complements TLS by providing displacement time series over large areas with millimeter-scale precision (Intrieri et al., 2018; Carlà et al., 2019). Persistent Scatterer InSAR (PS-InSAR) techniques are especially valuable in hyper-arid regions where low vegetation and stable reflectors improve coherence and reliability. Applications of InSAR at heritage sites – such as in Petra (Margottini et al., 2017), Pisa (Solari et al., 2016) or Civita di Bagnoregio (Bianchini et al., 2025) – have demonstrated its potential for detecting slow ground deformations threatening historical structures. However, only a few studies have tested InSAR monitoring in desert settings with strong topographic gradients and complex micro-reliefs typical of archaeological sites. Third, ambient vibration monitoring has gained traction as a tool for detecting internal structural changes in potentially unstable rock formations before surface deformations become visible (Weber et al., 2018; Moore et al., 2019; Bessette-Kirton et al., 2022; Leinauer et al., 2024). Frequency and damping shifts can indicate progressive weakening, and recent developments in portable instrumentation make it feasible to deploy such systems at remote or sensitive sites. Nonetheless, real-world applications at archaeological locations are rare, and the influence of strong diurnal temperature cycles typical of desert climates on measurement quality remains insufficiently studied.

All three methods provide critical data on the cliff's current state of stability and constrain areas of interest (AOI) for further hazard analyses. Here, numerical runout modelling tools such as “RApid Mass Movement” (RAMMS) are widely used in mountainous regions for hazard assessment and mitigation planning (Caviezel et al., 2019; Wendeler et al., 2017; Bolliger et al., 2024; Schraml et al., 2015). These models allow for the simulation of different failure types, including block falls and granular flows, and can incorporate digital terrain models derived from TLS or unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV) surveys. Although RAMMS was initially designed for Alpine environments, its use in hyper-arid desert contexts with anthropogenic terrain alterations remains underexplored. This is particularly relevant when assessing risk to archaeological sites where terrain morphology (e. g., “silent witnesses” of historic slope failures) has been altered by excavation or conservation activities.

To date, only isolated studies have attempted to integrate these complementary methods into a unified monitoring strategy tailored to cultural heritage sites. Especially in hyper-arid desert environments like Deir El-Bahari, there is a need for a benchmark study that demonstrates the feasibility, limitations, and synergies of TLS, InSAR, vibration monitoring, and runout modelling. This paper responds to that gap.

In this study, we aim to (i) detect recent rockfall activity and pre-failure deformation using multi-temporal TLS and Sentinel-1 PS-InSAR, (ii) parameterize and simulate realistic runout scenarios for both individual block falls and larger granular flows based on historic events, and (iii) assess the applicability of ambient vibration monitoring for early warning at a World Heritage Site in a hyper-arid environment. By integrating these non-invasive methods, we (iv) aim to identify zones of elevated hazard potential and contribute to a transferable safeguarding strategy for sensitive archaeological sites.

2.1 Temples of Deir El-Bahari

The Deir El-Bahari Valley is situated in the West Bank 5 km from the Nile River in the Theban Mountains opposite Luxor city. Apart from Deir El-Bahari the area features some of the most renowned cultural heritage sites of Egypt, such as the Valley of the Kings, Sheikh 'Abd El-Qurna or Dra Abu El-Naga. The complex of tombs and mortuary temples known as the Temples of Deir El-Bahari are dedicated to the many New Kingdom pharaohs over time. The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, built in the 15th century BCE during the New Kingdom, is the main temple in this complex. It is a unique and well-preserved structure that stands out for its architectural innovation and design. Designed by architect Senenmut, it features terraced levels, colonnades, and statues, dedicated to the sun god Amun-Ra, honouring Queen Hatshepsut's divine birth and pharaonic achievements (Ćwiek, 2014). Adjacent to Hatshepsut's temple, the Middle Kingdom's Temple of Mentuhotep II adds to the site's historical significance. The Temple of Thutmose III, wedged between the Temples of Hatshepsut and Mentuhotep II and carved partly into the rock, represents the New Kingdom era (Ćwiek, 2014).

Deir El-Bahari's cliffs boast tombs and chapels dedicated to various individuals, providing insight into the societal structure of ancient Egypt. This site is a testament to the cultural and artistic achievements of this civilization, encapsulating its historical depth and architectural prowess.

2.2 Geology

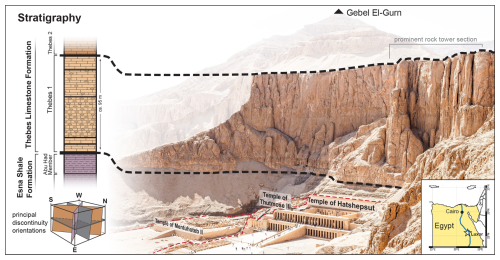

The terrain morphology of the study area resembles a Roman theatre-type shape, opening to the SE, featuring a width of ca. 200 m and relief of ca. 140 m (Fig. 1). Fluvial erosion and gravitational rock mass wasting processes, such as rockfalls or slides, were the main causes of the Valley's development in terms of morphology (Abdallah and Helal, 1990). Almost horizontally bedded rock members of Thebes Limestone Formation and Esna Shale Formation compose the cliffs of Deir El-Bahari (Said, 2017). The Esna Shale Formation is a heterogeneous succession of shales that is usually subdivided into four members (Abu Had, El-Mahmiya, Dababiya Quarry and El Hanadi Member) with a total thickness of more than 60 m (Aubry et al., 2016). The top Abu Had Member, which is composed of an alternation of marl and limestone beds with a few clayey intervals, is increasingly carbonate-rich and has a sharp stratigraphic contact with the overlying Thebes Limestone Formation at the base of the cliff at Deir El-Bahari (Aubry et al., 2009). The Thebes Limestone Formation is described in detail by (King et al., 2017), who subdivide the Formation into five depositional sequences (Thebes 1–5) forming five typical cliffs in Thebes Mountains (Fig. 1, greyed out towards Gebel El-Gurn). Thebes 1, the lowermost unit with a thickness of ca. 90 m, forms the main rock face of the cliff at Deir El-Bahari, and is composed of thinly laminated pinkish marl, nodular micritic limestone and thinly bedded argillaceous limestones (Fig. 1). A further stratigraphic subdivision is possible but not relevant for this study. Structurally, the lower Thebes Formation is a relatively soft and noticeably fractured limestone (Klemm and Klemm, 1993). In terms of geo-mechanics, the relatively many-layered geological setup (Dupuis et al., 2011) can be reduced to a typical “brittle on weak” structure (Erismann and Abele, 2001), i.e. a mechanically unstable configuration in which a competent, brittle rock mass overlies a weaker, ductile substrate, promoting differential deformation and shear localization that predispose the slope to failure.

Figure 1Topographic and geological setting of the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut within Deir el-Bahari (view towards west). In terms of geo-mechanics, the brittle Thebes Limestone on thinly layered Esna Shales (Dupuis et al., 2011) represent a typical “brittle on weak” structure.

Understanding and assessing the stability of the cliff above Deir El-Bahari requires an understanding of the structural geological framework as a crucial first step. Pawlikowski and Wasilewski (2004) state that faults and fissures are the two main structural features that affect the region. Reactivation of most of these faults and fissures is attributed to the Red Sea and Nile Valley tectonics during the Oligocene and Miocene. These tectonic activities have resulted in the normal (tensional) faults in Deir El-Bahari area, and the system of vertical fissures relates to them. The Thebes Limestone Formation is further dissected into several distinct rock towers (Fig. 1) by vertical joints with dip angles ranging from 85 to 90°, striking N-S, E-W, NE-SW, and NW-SE (Hesthammer and Fossen, 1999; Pawlikowski and Wasilewski, 2004; Beshr et al., 2021). A recent study by Ezzy et al. (2025) validates these joint trends by extracting discontinuities from our TLS data and provides further structural context. The geological setting constrains two general failure types that have either occurred in the past or postulated in the literature: (i) Single, locally constrained rockfalls ranging from ca. 0.01 to 25 m3 and (ii) the failure and collapse of larger magnitudes, such as one of the distinct rock towers. Evidence of small rockfalls (< 0.15 m3) is shown in our multi-temporal TLS data and larger single events are documented by Abdallah and Helal (1990). The potential failure of a rock tower has been already postulated in the literature (Chudzik et al., 2022) and is obvious in historic photographs (Naville, 1894, 1907, 1913). Due to the in situ fragmentation of the heavily jointed rock mass and internal shear stress during the failure process, we expect the failing material to transition into a granular flow type behaviour, sometimes referred to as dry flow (Hungr et al., 2014).

2.3 Historic evidence of gravitational mass movement activity

The geological and geomorphological characteristics of the cliffs of Deir El-Bahari Valley indicate a long history of gravitational mass movement. According to the archaeological evidence, the temple of Thutmose III, neighbouring the Temple of Hatshepsut in Deir El-Bahari, was destroyed and covered by a major rock wall collapse (Lipińska, 1977; Arnold, 1996) which can be attributed to an earthquake around 1100–1080 BCE (Karakhanyan et al., 2010). Badawy et al. (2006) stated that six major earthquakes occurred in Middle Egypt during historical times, nearly destroying the Ramses III temple in Luxor on the west bank of the River Nile. Abdallah and Helal (1990) documented two rockfall events close to the Temple of Hatshepsut, one of which (ca. 20 m3) reached the upper court of the Temple of Hatshepsut in 1985. They emphasized the potential for rockfall events from the cliff and demonstrated the rock wall's susceptibility for failure at Deir El-Bahari.

Historical imagery from archaeological digs dating from the late 1890s through the 1930s to the 1970s show several geomorphological features that could be attributed to gravitational mass movements (Naville, 1894; Winlock, 1942; Lipińska, 1977). However, major terrain alterations during these excavation campaigns introduce extensive bias regarding geomorphological analyses. This is especially the case for the temple of Thutmose III which was only discovered in the 1960s and used as a sediment dump during other digs (Lipińska, 2007). We therefore only relied on the earliest image by Naville (1894) of the site from 1892 before the excavation to identify evidence of two probable historic gravitational mass movements (Sect. 3.3.2).

3.1 Terrestrial Laser Scanning

TLS operates by measuring the time of flight or phase shift of the reflected laser signal, emitted from a ground-based instrument, to generate high-resolution, three-dimensional point clouds of surface geometry. In geosciences, TLS is widely applied for precise topographic mapping, monitoring geomorphic changes, and quantifying processes such as erosion, landslides, and rockfall dynamics (Jaboyedoff et al., 2012; Abellán et al., 2014; Shen et al., 2023). Various previous studies have shown the capabilities of TLS for rockfall monitoring (Abellán et al., 2010; Li et al., 2019; Kromer et al., 2017a; Hartmeyer et al., 2020b), kinematic landslide analyses (Santos Delgado et al., 2009; Kenner et al., 2022) and risk mitigation strategies (Gigli et al., 2014; Matasci et al., 2018) in particular. Recent developments also showcase its potential for early warning systems (Kromer et al., 2017b; Winiwarter et al., 2023).

Figure 2Map of the Deir EL-Bahari with the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut including repeated TLS Scan Positions, vibration measurements, and spatial extent of terrain for rockfall simulations.

We deployed a Riegl VZ-400 terrestrial laser scanner to obtain multi-temporal high-resolution topographic data and to perform a rock surface change detection. In late February 2022, TLS data was gathered at six locations around the Temple of Hatshepsut. In early March 2023, we repeated the scans at the previous positions and added ten additional scan positions to increase data coverage on top of the Deir El-Bahari cliff (Fig. 2). We used RiScan Pro for all raw data processing (filters, registration (Multi Station Adjustment), geo-referencing). The data sets of both scan epochs were each merged, homogenized, and trimmed to single 3D point clouds of Hatshepsut's Temple and the cliff behind. To generate a detailed digital surface model (DSM), the point cloud of March 2023 was manually edited in the open-source software CloudCompare to exclude tourists and optimize geomorphometric accuracy in the inner temple area (occluded flooring, roof structures, and pillars) before the final 2.5D rasterization. We applied linear interpolation for small, inevitable data gaps. We used the standard Multiscale Model to Model Cloud Comparison (M3C2) algorithm by Lague et al. (2013) to perform a topographic change detection, which we limited to the rock face, scree slopes, and retaining wall behind the temples of Deir El-Bahari. M3C2 is a well-established method for straightforward 3D change detection. It compares raw 3D point clouds and avoids gridding artifacts, interpolation errors and loss of detail in rough or vertical terrain. To distinguish unchanged areas from actual topographic change, we used a level of detection (LoD). The LoD accounts for instrumental error, controlled by the error propagation from raw data quality and registration process. This includes the scanner's target accuracy (5 mm @ 100 m range), precision (3 mm @ 100 m range), laser beam divergence (0.35 mrad) and atmospheric correction (RIEGL, 2014). In our analysis, we define the LoD as the threshold for statistically significant change (local 95 % confidence interval) using the M3C2 algorithm (Lague et al., 2013). For the visualization of our data, we worked with Cloud Compare and QGIS.

3.2 Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar

In landslide research, satellite-based InSAR is used to measure minute ground-surface displacements over time by detecting phase differences between repeated radar images, enabling early detection and monitoring of slope deformation at millimetre-scale precision (Ferretti et al., 2001; Colesanti and Wasowski, 2006; Spreafico et al., 2015; Dehls et al., 2025).

To analyse ground deformation in the vicinity of the Temple of Hatshepsut, a combined Small Baseline Subset (SBAS) and Persistent Scatterer Interferometry (PSInSAR) time series processing was carried out. The analysis was performed using the Python-based open-source software InSAR.dev (formerly PyGMTSAR Professional; Pechnikov, 2024) within a cloud-based Google Colab environment. A total of 93 Sentinel-1 IW SLC scenes in VV polarization from the ascending orbit (January 2021–February 2024) were processed. The acquisition on 6 April 2022 was used as the reference scene.

All scenes were automatically pre-processed using precise orbit data and the global Copernicus 30 m digital elevation model (DEM). After co-registration and reframing to the area of interest, geocoding was performed. To enhance data quality, the pixel stability function (PSFunction) was computed to suppress incoherent areas. Interferograms were generated using conservative thresholds (baseline < 150 m, temporal separation < 50 d) to minimize atmospheric effects and geometric decorrelation. Phase unwrapping was performed using SNAPHU (Chen and Zebker, 2002), followed by correction of trend and turbulence components through multiple regression models. The resulting SBAS time series were converted into Line-of-Sight (LOS) deformation and decomposed using Seasonal-Trend decomposition using locally estimated scatterplot smoothing (LOESS) (Cleveland, 1990). Subsequently, a high-resolution PSInSAR analysis was performed, in which the trend- and turbulence-corrected SBAS components were integrated into the PS phase. Only coherent pixels with an interferogram correlation greater than 0.5 were retained to exclude noisy time series and minimize atmospheric disturbances.

3.3 Runout Modelling

In this study we used the RAMMS-Software suite to simulate runout scenarios for the two main failure mechanisms at the Deir EL-Bahari cliff (Sect. 2.2) to produce a first evidence-based benchmark towards a comprehensive risk analysis. We used RAMMS::ROCKFALL for the simulation of single, locally constrained rockfalls ranging from ca. 0.01 to 25 m3 and RAMMS::DEBRISFLOW for dry granular flow parameterization of two probable historic, larger collapsed rock towers. As our monitoring data does not show any imminent larger rock wall failures, the granular flow simulation retained in a parameterization stage, focused on historic events. We used the RAMMS-software suite as it allows a comprehensive and intuitive modelling approach and straightforward parameterization.

3.3.1 Rockfall simulation

RAMMS::ROCKFALL is a numerical simulation tool that models rockfall trajectories, velocities, and impact forces using non-smooth rigid body mechanics coupled with hard contact laws. It integrates DEMs and material properties to assess hazard zones, optimize mitigation strategies, and support risk analysis in complex terrain (Caviezel et al., 2019). The rockfall module of RAMMS has been developed and widely tested in alpine, mid-latitude environments (Caviezel et al., 2021; Wendeler et al., 2017; Sala et al., 2019; Sellmeier and Thuro, 2017; Noël et al., 2023). Recently its application has been further adopted, also for more arid sites, such as southern Italy (Massaro et al., 2024) or Turkey (Utlu et al., 2023). Marija et al. (2022) were the first to apply rockfall simulation software (Conefall and Rockyfor3D) to Egyptian heritage sites in the Valley of the Kings. Ezzy et al. (2025) presented a first attempt to simulate single rockfalls at the Temple of Hatshepsut. However, potential release areas were solely constrained by the geotechnical setting, which, in the context of the intense jointing and structural preconditioning of the entire rock mass of Deir El-Bahari, limits their specificity. This work proposes an advancement of the simulation setup by (i) looking at areas showing actual activity and (ii) reducing complexity of parameters, providing a straightforward tool for conservative rockfall runout estimations.

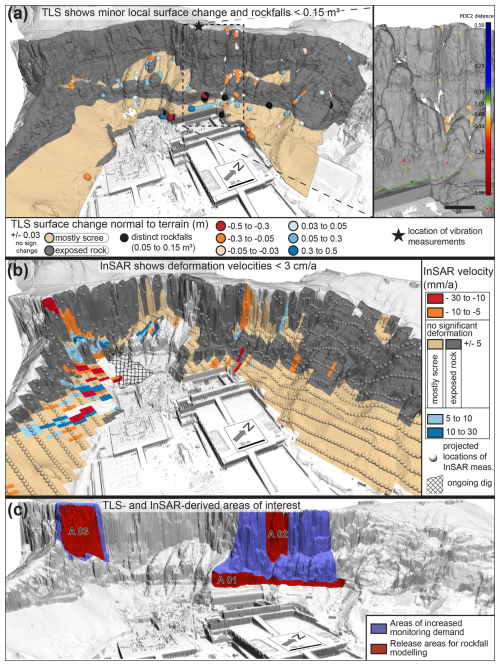

Figure 3(a) TLS change detection February 2022–March 2023 of the Deir EL-Bahari. Significantly changed areas appear in the detailed view of changes in point cloud in the top right panel. Changes due to excavations and anthropogenic terrain alterations were manually removed. (b) InSAR velocity trends over three years contextualized by surface material, i.e. scree and bare rock. (c) TLS- and InSAR-derived areas of interest for rockfall models.

We set up RAMMS::ROCKFALL models for three potential release areas, that we identified from the TLS and InSAR integration (Fig. 3c), which we labelled A 01, base of the Thebes Formation behind the Temple of Hatshepsut, A 02, rock tower above the Temple of Hatshepsut, and A 03, rock face at western Deir El-Bahari. For each release area we created four rockfall scenarios referring to the released block sizes of 0.01, 0.1, 2 and 25 m3. Here, 0.01 m3 corresponds to the five distinct rockfalls in our 1-year TLS data, and 25 m3 to the largest single rockfall reported for the last century (Abdallah and Helal, 1990) as well as larger distinct blocks in the cliff (Figs. S1 and S2 in the Supplement). We attributed these magnitudes to theoretical return periods (frequency) of 5, 1, 0.05 and 0.01 a−1, respectively. This magnitude frequency relation corresponds roughly to a power law (), which fits well in the range of other rockfall studies (Graber and Santi, 2022).

Key parameters for rockfall dynamics are rock shape, size and the terrain parameters (Caviezel et al., 2019; Caviezel et al., 2021). To obtain applicable rock shapes we gauged (i) the general shape of the occurred rockfalls in the TLS change detection and (ii) multiple larger blocks in or at the base of the cliff using our 3D point cloud (Figs. S1 and S2). This resulted in rock aspect ratios of ca. which refers to a “long” rock shape with rounded edges in RAMMS' Rock Builder. We estimated terrain parameters according to RAMMS AG (2024b) and chose “hard” for the scree slopes and “extra hard” for all solid rock surfaces (cliff and temple floor, Fig. 2). As suggested, we increased the ground dampening of the scree slopes slightly for the largest rock volumes (RAMMS AG, 2024b). With these rather high terrain categories we aim to produce a conservative estimate of potential runout lengths, as higher damping can potentially result in critically underestimated runout lengths. We used a 0.5 m grid resolution, and 20 random start orientations at every sixth grid point for all simulations. Please refer to Table S1 for a full list of parameters.

3.3.2 Granular flow simulation

As stated in Sect. 2.2, we expect a potentially failing and collapsing rock tower to transition into a dry granular flow type behaviour. To determine suitable parameters for potential granular flow events at the Temple of Hatshepsut, we calibrated two RAMMS::DEBRISFLOW scenarios. The model is based on the shallow water equations with a two-parameter rheology that accounts for both frictional and viscous flow properties (dry-Coulomb type friction μ and viscous-turbulent friction ξ). These friction parameters are the key control of model outcomes and therefore require proper calibration (Christen et al., 2012; Bartelt et al., 2015). Then, the model allows users to predict flow paths, velocities, impact forces, and deposition patterns using high-resolution DEMs (RAMMS AG, 2024a). RAMMS::DEBRISFLOW is widely applied in hazard assessment, risk management, and mitigation planning for debris flow-prone areas (Graf et al., 2019; Kumar et al., 2024). For example, Bertoldi et al. (2012), Schraml et al. (2015), Frank et al. (2017), or Zimmermann et al. (2020) simulated runout patterns for debris flow hazard mapping and provide valuable reconstruction approaches for alpine debris flows. Other studies have applied RAMMS::DEBRISFLOW to enhance our process understanding, e.g., constrain parameter spaces and the effect of grain size and flow composition (Bolliger et al., 2024), or study controls of debris flow erosion (Dietrich and Krautblatter, 2019). Apart from its dedicated field (i.e. debris flows), RAMMS has also been used to simulate and evaluate runout dynamics of rock(-ice) avalanches (Allen et al., 2009; De Pedrini et al., 2022) or rock avalanches on glaciers (Engen et al., 2024). Comparing those studies regarding the range of applied friction parameters, we found a stark increase in Coulomb type friction μ with decreasing water content in the moving mass (mean ca. 0.01–0.15 for debris flows up to 0.35 in rock(-ice) avalanches). We therefore expect high μ-values for the dry granular flows resulting from collapsed and channelized rock tower debris at Deir El-Bahari. Applications of RAMMS::DEBRISFLOW in completely dry environments are very rare or even carried out on different planets, such as Mars (de Haas et al., 2019).

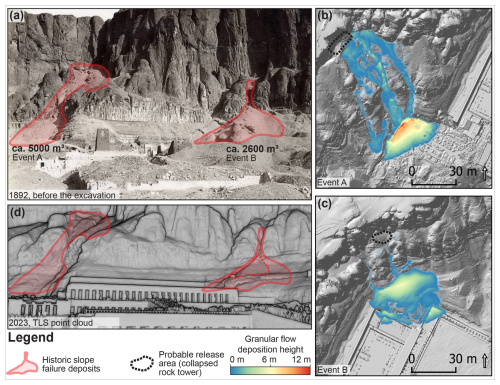

The oldest available photograph of the Temple of Hatshepsut from 1892 (Naville, 1894), shows two likely granular flow deposits of collapsed rock towers: Event A (ca. 5000 m3 or 100 m2 × 50 m height) behind the temple of Thutmose III and event B (ca. 2600 m3 or 52 m2 × 50 m) north of the Temple of Hatshepsut. To better constrain the volume of the failures we set out to reconstruct the deposition geometry with terrestrial and aerial photogrammetry and monoplotting. However, due to the intense and repeatedly anthropogenic terrain alterations and limited number of usable historic photographs, this approach led to little to no success. We therefore estimated release volumes from historic imagery, the 3D point cloud and simple geometric and morphometric assumptions of geomorphological features (Fig. S3) and archaeological reports of cliff cleaning missions (Zachert, 2014a, b, c). As these missions removed most of the scree on the slope area of event A, we assume to have obtained pre-failure slope coverage in our laser scans. To achieve the same for event B, the recent talus cone north of the Temple of Hatshepsut was removed and interpolated in the DSM. Start locations for events A and B were determined by a GIS-based flow path analysis and geomorphological study of the rock wall. For simplicity, we assume that for both model scenarios all material identified as possible historic rock slope failure was released at once using a 5 s hydrograph and an initial velocity of 15 m s−1 in the down slope direction. The initial velocity was estimated with a mean maximal vertical velocity of the collapsing mass of 20 m s−1 and coefficient of restitution considerations presented by Jackson et al. (2010). We iteratively calibrated the granular flow models by varying both friction parameters between 0.4 < μ < 0,8 and 100 < ξ < 5000 m s−2 and visually comparing the model results to the respective post-failure geomorphology (height and runout pattern of deposits). Please refer to Table S2 and Fig. S7 for a full list of parameters.

3.4 Vibration measurements

Ambient vibration monitoring in geosciences, especially for landslide precursor analysis, is used to detect subtle changes in a slope's natural resonance frequencies and damping characteristics, which can reveal evolving internal damage, crack formation, or progressive destabilization before visible movement occurs (Weber et al., 2018; Moore et al., 2019; Bessette-Kirton et al., 2022; Leinauer et al., 2024). In the scope of preliminary field tests, seismic measurements were recorded to determine which vibrational quantities are suitable precursors for sudden or gradual material changes in the rock needles behind the Temple of Hatshepsut. The considered methods include horizontal-to-vertical spectral ratios (HVSR), standard spectral ratios based on ambient noise (SSR), and the stochastic subspace identification (SSI). One sensor was placed at the top of the rock needle, and another was located in the gap between the rock needle and the plateau (Fig. 2).

The HVSR is a common tool to analyse the amplification of ground motions on site based on a single tri-axial sensor (Nakamura, 1989). Resonance frequencies can be extracted from HVSR curves as the x-value of predominant peaks. The SSR is another concept to describe the site amplification. It is defined as the earthquake spectrum of a reference site in comparison to the examined site. Therefore, SSR requires at least two uni-axial sensors, where one of them must be located on bedrock. A SSR beyond one describes the site amplification, and the peaks represent resonance frequencies. The stochastic SSI is an appropriate method to determine modal parameters of a structure (van Overschee and de Moor, 1995). SSI can be performed based on a single measurement channel. The method yields the natural frequency f_i and damping ratio ζ_i of each mode of vibration i. The algorithm requires the number of modes m to be set as a user input. Since this value is unknown a priori, the computation is repeated for a user-defined range of modes, and the model order of each solution is plotted against the frequencies in so-called stabilization diagrams (Sect. 4.5). Every method has a unique selling point. The SSI method is the only method that yields (undamped) natural frequencies fi and damping ratios in percent critical damping ζi. It is also the only method that does not depend on the user-defined frequency resolution. Although not shown here, SSI can also be used to estimate mode shapes. Modes shapes characterize the deflection pattern and the directivity of each mode of vibration, giving deeper insights into the most likely stress accumulations and failure scenarios. HVSR and SSR, on the other hand, give information on the spectral site amplification of ground motions. A detailed technical description of the data analysis is provided by Mendler et al. (2024). All three methods yield resonance frequencies of the underground, and this paper sets out to test and compare their effectiveness and robustness for exposed rock needles, such as the one behind the Hatshepsut temple. We used a Trillium Compact 120 s seismometer on 6 March 2023 (09:37 to 23:43 LT) with a sampling rate of 200 Hz.

4.1 Terrestrial Laser Scanning

The finished point clouds of our TLS campaigns show an almost full coverage of the Deir El-Bahari area, including temples, the cliff and the geometry of the most prominent rock pillars behind the Temple of Hatshepsut, including fissures running behind them. Both point cloud models have X, Y, and Z dimension of ca. 1000 × 650 × 200 m and contain ca. 85 Mio. points with a point-to-point distance of 0.05 m. The registration error for the first epoch (February 2022) was just over 0.01 m (standard deviation of residuals) whereas it was ca. 0.03 m for the second epoch (March 2023). The data of the latter was rasterized to DSMs with raster sizes of 0.1, 0.5 and 1 m for the purpose of runout modelling and data visualization.

Figure 3a shows the results of the surface change detection. For better visual accessibility, we subsampled the change detection to a point spacing of 0.25 m and 100 significantly changed points (from M3C2 analysis) in a radius of 1 m. The original change detection is shown in Fig. 3a (right side). Generally, the data does not reveal extensive rock face deformation above the LoD of ca. 0.03 m. Hence, no larger imminent mass movements were detected. At the base of the Thebes Formation five distinct small rockfalls source areas with magnitudes from 0.05 to 0.15 m3 occurred behind the Temple of Hatshepsut between the scan epochs, where one event most likely occurred as three smaller rockfalls. The deposits of these rockfalls are also detectable and are situated either outside the temple area or behind the retaining wall protecting the temple (Fig. 3a, right side). For an area of ca. 6.5 ha of exposed rock wall (Fig. S4), we calculated a total volume of five distinct rockfalls of 0.59 ± 0.05 m3 (Fig. S1), which translates to a rock wall retreat rate of ca. 0.009 ± 0.001 mm a−1. Minor sediment redistribution, recognizable by typical erosion and deposition patterns, is mostly restricted to the scree slopes, small gullies, and an area around a rock tower and its base north of the Temple of Hatshepsut. The data also show enhanced terrain alteration at an ongoing archaeological dig site behind the temples of Thutmose III and Mentuhotep II, neighbouring the Temple of Hatshepsut. These data are not shown in this study, but their location is disclosed in Fig. 3b.

4.2 Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar

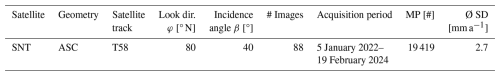

All available satellite tracks from the Sentinel-1 (SNT) mission were processed to generate a comprehensive InSAR dataset. The temporal distribution of the acquisitions is shown in Table 1 and Fig. S5. Over the full observation period, more than 19 000 measurement points were identified in 1 km2, with an average standard deviation of 2.7 mm a−1 for the estimated displacement velocities (Table 1).

Table 1Used InSAR datasets, number of measurement points (MP), and standard deviation of the analysed InSAR data sets.

The processed InSAR data reveal deformation velocities of up to 30 mm a−1 in the immediate vicinity of the temple complexes (Fig. 3b). Due to the C-band wavelength of Sentinel-1 and the applied processing method, each measurement point integrates surface motion over an area of approximately 60 m2 (pixel resolution: 4 × 15 m). By integrating three years of satellite data and applying time series curve fitting, LOS velocities were derived for each persistent scatterer. Based on the statistical characteristics of the dataset, velocities exceeding ±5 mm a−1, approximately corresponding to double the standard deviation, are considered significant (see Table 1). To contextualize the spatial patterns, the study area was subdivided into exposed rock (i.e., the cliff) and adjacent scree deposits. The analysis yields four key observations: (i) Widespread stability – The majority of the terrain, including most parts of the rock face surrounding the temples, does not exhibit significant displacement. (ii) Localized rock face activity – Significant velocities within the cliff area are restricted to small zones, specifically, at the base of the cliff, a rock tower north of the Temple of Hatshepsut, and a slope area west of the Temple of Mentuhotep II (Fig. S6). (iii) Data gaps – Central parts of the site show sparse or missing data, mainly due to radar shadowing from steep terrain or phase decorrelation, potentially linked to archaeological excavations. (iv) Activity in scree deposits – The most pronounced and spatially extensive deformation is observed in the scree southeast of the Temple of Mentuhotep II, suggesting increased susceptibility to surface movement in these unconsolidated materials.

4.3 Identification of areas of interest

The combination of TLS and InSAR analyses allow for joint interpretation and the definition of AOIs. In the area behind the Temple of Hatshepsut both the TLS and InSAR measurements result in similar patterns: several small rockfalls, scree redistribution and aeras with statistically significant InSAR velocities are evident at the base of the cliff. Furthermore, there are patches of negative surface changes just above the LoD (0.03 m) around and below a distinct rock tower north of the temple, and statistically significant ground movement towards the radar sensor are in the same spot. These two regions of potential rockfall activity are defined as release areas A 01 (base of the cliff) and A 02 (rock tower) for the rockfall runout activity. We further suggest that, based on our results, the area behind the Temple of Hatshepsut has an increased monitoring demand (Fig. 3c). The same is true for a patch of rock wall in the western part of Deir El-Bahari, defined as rockfall release area A 03 (Fig. 3c, left; Fig. 4). Here, the InSAR results show statistically significant ground movement that is below the TLS threshold.

4.4 Runout Modelling

4.4.1 Rockfall simulation

Figure 4 shows the results of the rockfall runout modelling. We chose to depict the total reach probability of released rocks per scenario to highlight (i) maximum runout lengths and (ii) probable travel paths at each AOI. A total of 93,600 simulations were performed to produce statistically sound results. The figure illustrates that rocks from release scenarios A 01 and A 02 have a certain probability (3.8 %–18.1 %) of reaching the accessible area of the Temple of Hatshepsut while rocks from scenario A 03 do not reach it in the model. The rocks from A 03, however, do reach the ancient temples of Mentuhotep II and Thutmose III, which are not accessible to the public. Rocks from scenario A 01 (base layer of Thebes Formation) generally have a lower probability of reaching the temple than scenario A 02 (rock tower above the Temple of Hatshepsut) and are mostly deposited on the retaining wall behind the Temple. The number of rocks deposited in the Temple of Hatshepsut visitor area increases with the size of the released blocks, as larger blocks tend to travel farther. However, the difference between the smallest (0.01 m3) and largest rocks (25 m3) is rather low, with total reach probabilities ranging from 3.8 % to 13.6 % for scenario A 01 and from 12.3 % to 16.1 % for scenario A 02.

4.4.2 Granular flow simulation

Figure 5a shows the two historic slope failure deposits we identified for our subsequent model parameterization. Both deposits exhibit (i) typical cone shape geometry, (ii) an intermixture of large rock fragments that indicate remnants of the collapsed rock tower, and (iii) at event A a comparatively thick scree cover with boulders on the slope above the furthest deposits.

Figure 5(a) Earliest historic photograph of the Temple of Hatshepsut before the first major excavation (Naville, 1894) shows two distinct deposits that indicate previous rock slope failure. (b, c) Results of the dry flow simulations for historic rock tower collapses and subsequent granular flow. (d) Current 3D TLS point cloud displaying the recent talus cone, marked by the red dashed line. This was removed from the model before the simulations to indicate pre-failure conditions.

Figure 5b and c show the simulation results (deposition height) for the overall best fitting internal friction parameters of μ = 0,65 und ξ = 800 m s−12 (all calibration scenarios in Fig. S7). The height and spatial distribution of the simulated deposits show a good fit to the geomorphological condition prior to the excavations at the Temple of Hatshepsut. Simulations of event A show (i) major deposits in the Thutmose III temple perimeter, that would have caused considerable damage to the former structure, and (ii) relatively extensive deposits on the slope. Event B shows a wide, cone-shaped deposit in the simulation and some spill in today's reconstructed temple complex. Of course, the event would have happened long before reconstruction, therefore, unequivocal validation of the runout remains a challenge.

4.5 Vibration measurements

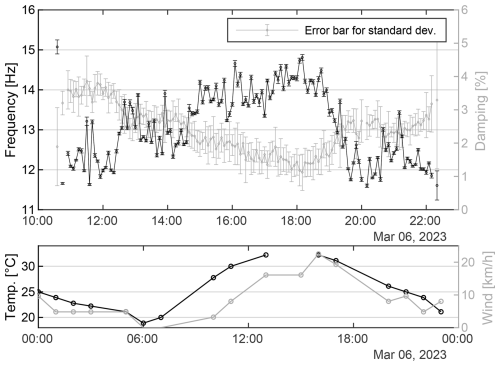

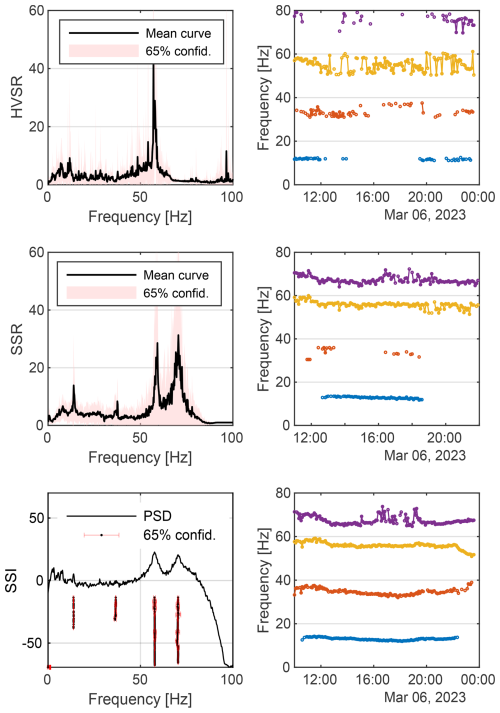

The results of the vibration monitoring are summarized in Fig. 6, which displays representative HVSR, SSR spectra and a SSI stabilizing diagram, and the permanent tracking of the extracted frequencies. The uncertainty in the measurements is quantified through the 65 % confidence intervals for HVSR and SSR curves (light red), and error bars equivalent to the 65 % confidence interval for the SSI.

Figure 6Extracted ambient seismic vibration frequencies of the rock towers above the temple of Hatshepsut based on HVSR, SSR, and SSI techniques.

The extracted frequencies are similar for all methods, with values of about 13, 34, 56, and 67 Hz. The SSI method appears to be most suited for long-term monitoring, as it is the only method that can continuously identify all four modes of vibration, even the weakly excited mode around 34 Hz which does not lead to a peak in the power spectral density (Fig. 6 bottom). The most dominant mode around 56 Hz is reliably identified by all three methods. Where HVSR fails to reliably identify the other modes, SSR appears more suitable for the estimation of high-frequency modes, such as the one around 67 Hz.

Sudden changes in frequencies or damping ratios can be indicators of material changes in the rock; however, vibrational modes also oscillate due to environmental effects, such as material temperature and moisture content. In this preliminary study, the compounding effects are not measured, but Fig. 7 shows the SSI-based natural frequency and damping ratios, together with the ambient temperature and wind speed measured at a nearby weather station in Luxor. The damping ratio shows the most distinct changes ranging from 1 % to 4.2 %. On close inspection, the correlation between the variables becomes obvious: increasing ambient temperatures lead to decreasing frequencies and higher damping ratios. The correlation becomes more obvious when a time lag of a few hours is considered, as vibration behaviour depends on the material temperature and not the ambient temperature. Further technical insights and results are addressed in Mendler et al. (2024).

5.1 Terrestrial Laser Scanning

The TLS surveys produced vital data for DSM generation (the basis for all runout simulations and topographic analyses) and surface change detection. The LoD of ca. 3 cm is in the range or below comparable topographies (Santos Delgado et al., 2009; Abellán et al., 2010; Jacobs and Krautblatter, 2017; Mohadjer et al., 2020). As stated above, we defined the LoD as the threshold for statistically significant change (local 95 % confidence interval) using the M3C2 algorithm (Lague et al., 2013). Throughout the rock face, this threshold, i.e. 3 cm, also corresponds well to the 95th percentile of the distribution of all computed model distances, an approach to define LoD in other studies (Abellán et al., 2011). Our data show that environmental conditions at Egyptian heritage sites can have a major impact on data quality and thus on the LoD. Relative humidity is generally very low which positively affects accuracy (alignment std. dev. 0.01 m for February 2022 data), but desert dust and drastic diurnal atmospheric temperature variations can have the opposite effect (Witte and Schmidt, 2006). This became an issue for the second TLS campaign (March 2023), where extensive filtering in some point clouds was needed to reduce residual distances to 0.03 m.

Despite the high degree of rock mass fragmentation, compared to other TLS-based rockfall studies, the calculated retreat rate, and hence the rockfall activity, is very low (Abellán et al., 2010; Jacobs and Krautblatter, 2017; Strunden et al., 2015; Draebing et al., 2024). We attribute this to a lack of climatic controls (e.g., rain, moisture, freezing) that are limited to thermal erosion (Collins and Stock, 2016) and seismic acceleration. However, we stress that in a rare case of significant precipitation event a stark increase in rockfall activity is highly probable (Krautblatter and Moser, 2009). This is particularly important as regional precipitation patterns in Egypt are expected to change due to global climate change (Gado et al., 2022).

All few detected distinct rockfalls are restricted to the very base of the cliff, which we attribute to increased topographic differential stress. Over long time scales this erosion pattern can lead to oversteepening, reducing the cliff's toe support (Rosser et al., 2013) and promoting larger instabilities. The size and shape, as well as scarp geometry, of the released primary rockfalls indicate a strong link to the dominating joint orientation in the cliff and support the rock shape used in our rockfall simulation. Similar to other studies (Ruiz-Carulla et al., 2020; Gili et al., 2022) we observed intense fragmentation of the released material, even from very low drop heights (Fig. 3a) resulting from heavy internal fracturing of the rock mass. As we only observed distinct rockfalls from the lowest subunit of the heterogeneously layered Thebes 1 formation, we cannot reliably extrapolate this degree of fragmentation to rockfall from all potential release zones or AOIs respectively. Nonetheless, fragmentation is a key control of rockfall runout dynamics, as kinetic energy is dissipated in the process (Wyllie, 2017). Scree redistribution pattern in the TLS change detection on the talus slopes (Fig. 3a) are either linked to small trails or small gullies in the rock mass where minor disturbances (workers or very small rockfalls) can result in small granular flows in the scree deposited at its angle of repose.

This study shows that TLS in the context of safeguarding cultural heritage in hyper-arid regions is very well suited for high-resolution surface change/rockfall detection. Rapid change of local atmospheric conditions (e.g., temperature, dust) may reduce data quality on a short-term basis. Other studies have shown that TLS is well-suited for detecting larger slope instabilities even before eventual failure (Santos Delgado et al., 2009; Jacobs et al., 2024; Kenner et al., 2022). A drawback of the current integration TLS in our approach is temporal resolution, as critical pre-failure deformation or acceleration in the cliff is possibly lost between measuring epochs. Depending on future safety demand, we aim to extent the multi-temporal TLS data set to (i) increase our understanding of rockfall dynamics at the Temple of Hatshepsut, (ii) potentially detect larger instabilities prior to failure or (iii) integrate a TLS system in a 4D early warning system (Gaisecker and Czerwonka-Schröder, 2022; Winiwarter et al., 2023).

5.2 Interferometric Synthetic Aperture Radar

The combination of SBAS and PSInSAR methods proved to be an effective approach for high-resolution deformation analysis around the Temple of Hatshepsut. While SBAS enables a robust detection of areal deformation (Berardino et al., 2002), PSInSAR provides highly precise point-based information in urban and rocky zones (Ferretti et al., 2001). Integrating the SBAS-based trend and turbulence corrections into the PS time series significantly improved phase stability and reduced potential bias effects.

The analysis indicates that most of the study area remained stable over the 3-year observation period. Localized deformation occurs primarily at the base of the cliff, around a rock tower north of the temple, and along slopes west of the Temple of Mentuhotep II. These zones correspond to potential instabilities previously identified through TLS and field observations, confirming the high consistency between the methods.

The accuracy of interferometric SAR analyses is mainly influenced by orbit errors, inconsistencies in the DEM, phase unwrapping errors, decorrelation effects, and atmospheric signal delays (Hanssen, 2003; Ferretti et al., 2011). No explicit atmospheric correction (e.g., using GACOS) was applied; instead, atmospheric disturbances were minimized by selecting interferograms with short spatial and temporal baselines and by restricting the analysis to coherent pixels (correlation > 0.5).

The mean standard deviation of annual deformation rates across the study area is 2.7 mm a−1, which lies at the lower end of values reported for comparable Sentinel-1 applications at World Heritage Sites (Margottini et al., 2017; de Falco et al., 2022; Bianchini et al., 2025). These results demonstrate the high internal precision of the applied SBAS/PS-InSAR workflow and confirm its suitability for hyper-arid and topographically complex environments.

Potential error sources mainly result from incomplete phase unwrapping in steep terrain and small-scale atmospheric gradients. Nevertheless, the high coherence in rocky and anthropogenically influenced zones confirms that InSAR time series analysis provides a reliable tool for preventive monitoring of sensitive archaeological structures. Future work should include descending orbit data and external atmospheric models to better separate vertical and horizontal displacement components and quantify tropospheric effects. The combination with TLS or vibration monitoring could further improve temporal resolution and enable continuous early-warning monitoring.

5.3 Runout Modelling

5.3.1 Rockfall simulations

The results of the rockfall runout simulations are mostly dependent on rock shape, size and the terrain parameters (Caviezel et al., 2019, 2021; RAMMS AG, 2024b). We chose a “long” rock shape with an aspect ratio of ca. 1 × 0.6 × 0.5, as this proved to be the best fit for the site (see Sect. 3.3.1) and are congruent with structural analyses by Ezzy et al. (2025). Principally, other rock shapes cannot be ruled out entirely and should be addressed in future in-depth analyses. The terrain parameters in our model are relatively simple and hard, compared to other studies from mountainous areas (Noël et al., 2023; Massaro et al., 2024). This reflects the total lack of vegetation or softer organic soil cover at the study site. Furthermore, harder terrain types serve as a conservative estimate and are consistent with RAMMS AG (2024b) as references from entirely unvegetated environments are scarce. As block shape is generally constrained by the rock mass structure and seasonal changes in terrain parameters are highly improbable (e. g., moisture, vegetation, soil cover) the model is only sensitive to rockfall magnitudes. At the same time, calibrating terrain parameters with rockfall remnants on site is heavily biased as the entire plain of Deir El-Bahari has been dug out and meticulously cleaned from debris in at least four different archaeological campaigns (Naville, 1894; Winlock, 1942; Lipińska, 1977; Zachert, 2014a). Therefore, existing rockfall deposits outside the temple perimeter may represent statistical outliers or even anthropogenic deposits or redepositions rather than reliable calibration events. Therefore, a classic sensitivity analysis is not effective.

The results show less influence of rockfall magnitudes on runout length than anticipated. This is, however, consistent with Caviezel et al. (2021) and can, in this case, also be attributed to the large vertical component of the trajectory and the high DSM surface roughness in the archaeological sites (especially Scenario A 03, temple of Mentuhotep), as RAMMS::ROCKFALL does not allow plastic deformation of the surface model – in this case archaeological structures. The results of our TLS-based rockfall detection show that all detected rockfalls intensely fragment upon their deposition, resulting in energy dissipation (see Sect. 5.1). As our simulations cannot account for fragmentation during the rockfall trajectory, we probably overestimate total reach probabilities to some extent underlining the conservative nature of our rockfall simulations (Corominas et al., 2019). This becomes especially obvious in the case of the effect of the retaining wall behind the Temple of Hatshepsut. Originally built in 1968 to stabilize the soft Esna Shale formation immediately above the festival courtyard and the entrance to the Amun shrine (Lipińska, 1977), the retaining wall serves as a natural rockfall collector for smaller and intensely fragmented rockfalls. However, rockfalls with higher kinetic energy and lower amount of fragmentation have a higher probability of reaching the temple visitor perimeter. It is important to note that reach probabilities do not include incident probabilities which are key for future work towards risk assessment. In summary, our rockfall runout simulation offers a first, straightforward and conservative approach towards evidence-based rockfall hazard assessment at the Temple of Hatshepsut.

5.3.2 Granular flow simulations

As rockfalls in the geological context of Deir El-Bahari exhibit a large susceptibility to fragmentation (Sect. 5.1), the granular flow simulations produced valuable insights into potential runout scenarios, especially for larger magnitudes. RAMMS::DEBRISFLOW was originally developed for the simulation of debris flows and its application in completely dry environments may seem counterintuitive. However, in the case of this study it turned out to be a simple and geomorphologically sound simulation tool for dry flows (granular flow), too. The model calibration (see Fig. S7) produced high values for the dry-Coulomb type friction μ, compared to simulated and calibrated debris flows (Bolliger et al., 2024) and rock avalanches (Engen et al., 2024). According to RAMMS AG (2024a) the Coulomb friction corresponds to the tangent of the internal shear angle of the material (φ). The calibrated μ = 0.65 (±0.05) corresponds to φ = 33° (±2°). This matches the natural slope angle β of the surrounding talus slopes that were deposited at their angle of repose by gravitational mass movements, and supports our findings, as without external forces no initial movement parallel to the slope is possible if arctan (μ) > β (Salm, 1993). Since in the case of dry granular flows there is no lubrication effect of water (RAMMS AG, 2024a) and slope failure magnitudes are not large enough to drastically change the transport dynamics (Erismann and Abele, 2001), we consider our results appropriate for the described failure process. The runout and height of the deposits are therefore mainly controlled by μ, whereas viscous-turbulent friction ξ controls velocity and the amount of material deposited around the release area or in the channel. In fact, Fig. S7, showing the range of appropriate μ–ξ pairs, suggest a low sensitivity of flow reach to changes in ξ, in dry granular flows.

Since information on release volumes is limited to single historic photographs, anthropogenic terrain alterations are massive, and our remote sensing data do not suggest distinct imminent unstable volumes, the simulated granular flow magnitudes are rough geometric estimates and assume spontaneous rather than successive failure. They translate to rock towers with a height of ca. 40–50 m and a footprint of 65–100 m2, which is very similar to other rock towers structures at the Deir El-Bahari cliff. Therefore, our simulation provides key parameters for the simulation of potential, larger future events. In case of successive failure of such rock towers, we expect shorter runout distances. This underlines our rather conservative simulation scenarios at the current stage of the study.

5.4 Vibration measurements

This paper demonstrated the advantages of the SSI method for vibration monitoring. It is the only method that estimated all modes of vibration with high accuracy and a short measurement duration (of 5 min). Unusual weather events, seismic acceleration or subcritical fracture propagation may lead to erosion and cracks within the material, reduced compound stiffness, and hence, irregular changes in the frequency and damping values. Therefore, vibration-based features can be suitable precursors for rockfalls and could be employed to inform authorities and give them the opportunity to initiate on-site investigations, or to rerun the TLS and InSAR analyses on demand.

The study highlights that environmental changes affect the vibrational behaviour of the examined rock tower. Damping ratios appeared to be particularly susceptible to changes in environmental factors, and consequently, material changes (Fig. 7). To be able to distinguish normal changes from structural damage, the seismic station must be equipped with sensors that measure environmental variables that influence the vibration behaviour of the rock tower. Moreover, measurement data from an entire seasonable cycle (one year), or better two, needs to be measured to train smart algorithms to detect anomalies and quantify long-term shifts.

5.5 Discussion of safeguarding and hazard anticipation strategy

The multi-method assessment at Deir El-Bahari demonstrates that integrating TLS, InSAR, vibration monitoring, and runout modelling provides a more comprehensive and reliable understanding of cliff stability combining the complementary information of several individual techniques. While TLS and InSAR independently reveal largely stable conditions – showing that most surface change is confined to scree slopes altered by archaeological activity – the combined interpretation of both datasets allows us to distinguish surface noise from meaningful deformation patterns. Importantly, the independent detection of two localized active zones by both TLS and InSAR, and a third zone detected by InSAR alone, highlights their complementary capabilities across different spatial and temporal scales. TLS provides high-resolution geometric changes at the vertical cliff face and in structurally complex zones, whereas InSAR provides long-term deformation trends across the entire study area with millimetric precision, however, low spatial resolution. Noteworthy is the exceptionally high quality of the remote sensing data, which can be largely attributed to the favourable environmental conditions at the study site. The integration of ambient vibration monitoring has the potential of further closing the scale gap between these methods by offering a continuous, real-time detection capability for abrupt mechanical changes that may occur between TLS epochs or satellite acquisitions. Together, these methods form a coherent, multi-scale monitoring system in which each approach validates, refines, or supplements the others.

This integrated perspective is equally important for hazard anticipation. The three AOIs identified through the combined remote-sensing analysis provide the spatial framework for rockfall and granular flow simulations. Here, the modelling results gain meaning only through their connection to the observational data: TLS-detected fragmentation patterns explain why conservative assumptions in runout simulations tend to overestimate reach, while InSAR-derived stability outside the three zones helps constrain the spatial extent of plausible failure scenarios. Likewise, vibration monitoring offers an early-warning potential for these very zones by revealing precursor frequency changes before geometric displacements become detectable. Thus, the modelling and monitoring components are not isolated steps but mutually reinforcing elements within an integrated safeguarding strategy.

Although the runout and granular flow models represent conservative first-order estimates due to limited calibration information, their integration with TLS-derived rockfall characteristics and InSAR-based deformation trends already provides a robust decision-support basis. The granular flow calibration, despite its reliance on rough volume estimates, offers robust friction parameters for future scenario testing, while the rockfall simulations help delineate areas where protective measures or access management could be most effective. By combining high-resolution DSMs, 3D change detection, InSAR-based deformation trends, dynamic behavioural indicators, and physically based modelling, this study demonstrates that a non-invasive multi-method approach produces a more reliable and nuanced hazard anticipation framework for the cultural heritage of Deir El-Bahari than any single dataset could achieve.

The Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, a key World Heritage Site from the fifteenth century BCE and part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site of Ancient Thebes, exhibits a unique architectural integration in the context of the Deir El-Bahari 100 m high subvertical rock cliff with prominent rock tower structures exposing the temple complex and its visitors to potential gravitational mass movements. Therefore, a comprehensive and reliable natural hazard safeguarding strategy is required. For the first time, we successfully combined three non-destructive measuring methods (TLS, InSAR, ambient vibrations) at an Egyptian World Heritage Site to provide a proof of concept of an integrated methodological approach and its capabilities towards a hazard anticipation and mitigation strategy. We show that

-

The combination of TLS and InSAR at heritage sites in desert environments provides unequivocal rock surface change analysis with good spatial resolution and beyond previously described accuracy in other settings.

-

Accurate and unambiguous rock surface change detection is only achievable by the combination of both methods.

-

Three local zones of significant deformation and surface change could be derived from the remote sensing data.

-

Ambient vibration measurements have great potential to bridge the time gap between the initiation of potentially preparing rock wall instability and active process monitoring especially in rock towers with sensitive ambient signals.

-

Straightforward rockfall and dry granular flow runout simulations provide valuable insights towards gravitational mass movement hazard assessment.

-

This study shows the remarkable potential of transferring established methods from mountainous regions to cultural heritage sites.

-

We presented an integrated approach in a challenging climatic, geomorphological and archaeologically sensitive environment, and produced the first evidence-based event and impact analysis of gravitational mass movements at the Temple of Hatshepsut, providing vital data towards future risk assessment.

The data is available upon reasonable request and authorization of the Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities.

The supplement related to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.5194/esurf-14-55-2026-supplement.

HH and CG initiated the study and collaboration. BJ, MKe, MKr and MI designed the outline of the study in close cooperation with HH and CG. BJ, MI, ME, MKe, MKr, CG and HH conducted the field work in a joint effort. BJ analysed the TLS data, simulated runouts, and prepared and compiled the manuscript & figures with contributions from MI, ME and HH (Geological Engineering and Rock mechanics), MKe (InSAR), AM (ambient vibration), JK (granular flow modelling) and revision and final approval from all authors.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a member of the editorial board of Earth Surface Dynamics. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

We thank the Supreme Council of Antiquities in general and the Antiquities Area 465 manager and employees at El-Deir El-Bahari region for their local support. We are very grateful for support from Dr. Alexander Schütze (LMU Institute for Egyptology and Coptology) providing access to literature and photographs. We thank Dr. Christian Haberland (GFZ Potsdam) for providing instruments for ambient vibration measurements. The team is grateful to the ScanPyramids mission for their consistent support.

AI-statement: The authors used LLMs exclusively to assist with grammar and language editing. No content or interpretations were generated by AI.

We thank Fritz Schlunegger and Jakob Rom for their fair and constructive reviews, which greatly helped improving the quality of the manuscript.

The study was funded by the TUM Global Incentive Fund 2022: HERITAGE – High-energy rockfall impact anticipation in a German-Egypt cooperation.

This paper was edited by Joris Eekhout and reviewed by Fritz Schlunegger and Jakob Rom.

Abdallah, T. and Helal, H.: Risk evaluation of rock mass sliding in El-Deir El-Bahary valley, Luxor, Egypt, Bulletin of the International Association of Engineering Geology-Bulletin de l'Association Internationale de Géologie de l'Ingénieur, 42, 3–9, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02592614, 1990.

Abellán, A., Calvet, J., Vilaplana, J. M., and Blanchard, J.: Detection and spatial prediction of rockfalls by means of terrestrial laser scanner monitoring, Geomorphology, 119, 162–171, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2010.03.016, 2010.

Abellán, A., Vilaplana, J. M., Calvet, J., García-Sellés, D., and Asensio, E.: Rockfall monitoring by Terrestrial Laser Scanning – case study of the basaltic rock face at Castellfollit de la Roca (Catalonia, Spain), Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 11, 829–841, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-11-829-2011, 2011.

Abellán, A., Oppikofer, T., Jaboyedoff, M., Rosser, N. J., Lim, M., and Lato, M. J.: Terrestrial laser scanning of rock slope instabilities, Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 39, 80–97, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.3493, 2014.

Alcaíno-Olivares, R., Perras, M. A., Ziegler, M., and Leith, K.: Thermo-Mechanical Cliff Stability at Tomb KV42 in the Valley of the Kings, Egypt, in: Understanding and Reducing Landslide Disaster Risk: Volume 1 Sendai Landslide Partnerships and Kyoto Landslide Commitment, edited by: Sassa, K., Springer International Publishing AG, Cham, 471–478, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-60196-6_38, 2021.

Allen, S. K., Schneider, D., and Owens, I. F.: First approaches towards modelling glacial hazards in the Mount Cook region of New Zealand's Southern Alps, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 9, 481–499, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-9-481-2009, 2009.

Arnold, D.: Die Tempel Ägyptens: Götterwohnungen, Baudenkmäler, Kultstätten, Bechtermünz, Augsburg, ISBN 3860472151, 1996.

Aubry, M.-P., Berggren, W. A., Dupuis, C., Ghaly, H., Ward, D., King, C., Knox, R. W. O., Ouda, K., Youssef, M., and Galal, W. F.: Pharaonic necrostratigraphy: a review of geological and archaeological studies in the Theban Necropolis, Luxor, West Bank, Egypt, Terra Nova, 21, 237–256, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3121.2009.00872.x, 2009.

Aubry, M.-P., Dupuis, C., Berggren, W. A., Ghaly, H., Ward, D., King, C., Knox, R. W. O., Ouda, K., and Youssef, M.: The role of geoarchaeology in the preservation and management of the Theban Necropolis, West Bank, Egypt, Proceedings of the Yorkshire Geological Society, 61, 134–147, https://doi.org/10.1144/pygs2016-366, 2016.

Badawy, A., Abdel-Monem, S. M., Sakr, K., and Ali, S.: Seismicity and kinematic evolution of middle Egypt, Journal of Geodynamics, 42, 28–37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jog.2006.04.003, 2006.

Bartelt, P., Valero, C. V., Feistl, T., Christen, M., Bühler, Y., and Buser, O.: Modelling cohesion in snow avalanche flow, J. Glaciol., 61, 837–850, https://doi.org/10.3189/2015JoG14J126, 2015.

Berardino, P., Fornaro, G., Lanari, R., and Sansosti, E.: A new algorithm for surface deformation monitoring based on small baseline differential SAR interferograms, IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing, 40, 2375–2383, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2002.803792, 2002.

Bertoldi, G., D'Agostino, V., and McArdell, B. W.: An integrated method for debris flow hazard mapping using 2D runout models, in: Conference proceedings, 12th Congress INTERPRAEVENT, ISBN 9783901164194, 2012.

Beshr, A. M., Kamel Mohamed, A., ElGalladi, A., Gaber, A., and El-Baz, F.: Structural characteristics of the Qena Bend of the Egyptian Nile River, using remote-sensing and geophysics, The Egyptian Journal of Remote Sensing and Space Science, 24, 999–1011, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejrs.2021.11.005, 2021.

Bessette-Kirton, E. K., Moore, J. R., Geimer, P. R., Finnegan, R., Häusler, M., and Dzubay, A.: Structural Characterization of a Toppling Rock Slab From Array-Based Ambient Vibration Measurements and Numerical Modal Analysis, J. Geophys. Res.-Earth Surface, 127, https://doi.org/10.1029/2022JF006679, 2022.

Bianchini, S., Palamidessi, A., Centauro, I., Tofani, V., Spizzichino, D., and Tapete, D.: Satellite radar interferometry for the assessment of ground instability at a cultural heritage site: the case study of Civita di Bagnoregio, Italy, Rivista Italiana di Geotecnica, 1302, 67–78, https://doi.org/10.19199/0557-1405.rig.25.008, 2025.

Bolliger, D., Schlunegger, F., and McArdell, B. W.: Comparison of debris flow observations, including fine-sediment grain size and composition and runout model results, at Illgraben, Swiss Alps, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 24, 1035–1049, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-24-1035-2024, 2024.

Carlà, T., Intrieri, E., Raspini, F., Bardi, F., Farina, P., Ferretti, A., Colombo, D., Novali, F., and Casagli, N.: Perspectives on the prediction of catastrophic slope failures from satellite InSAR, Scientific Reports, 9, 14137, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50792-y, 2019.

Caviezel, A., Lu, G., Demmel, S. E., Ringenbach, A., Bühler, Y., Christen, M., and Bartelt, P.: RAMMS:ROCKFALL – A Modern 3-Dimensional Simulation Tool Calibrated on Real World Data, 53rd U.S. Rock Mechanics/Geomechanics Symposium, https://www.dora.lib4ri.ch/wsl/islandora/object/wsl:22147 (last access: 14 January 2026), 2019.

Caviezel, A., Ringenbach, A., Demmel, S. E., Dinneen, C. E., Krebs, N., Bühler, Y., Christen, M., Meyrat, G., Stoffel, A., Hafner, E., Eberhard, L. A., Rickenbach, D. von, Simmler, K., Mayer, P., Niklaus, P. S., Birchler, T., Aebi, T., Cavigelli, L., Schaffner, M., Rickli, S., Schnetzler, C., Magno, M., Benini, L., and Bartelt, P.: The relevance of rock shape over mass-implications for rockfall hazard assessments, Nature Communications, 12, 5546, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25794-y, 2021.

Chen, C. W. and Zebker, H. A.: Phase unwrapping for large SAR interferograms: statistical segmentation and generalized network models, IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing, 40, 1709–1719, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2002.802453, 2002.

Christen, M., Bühler, Y., Bartelt, P., Leine, R., Glover, J., Schweizer, A., Graf, C., McArdell, B. W., Gerber, W., Deubelbeiss, Y., Feistl, T., and Volkwein, A: Integral hazard management using a unified software environment, in: 12th Congress Interpraevent, 77–86, http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11850/61165 (last access: 14 January 2026), 2012.

Chudzik, P., El Younsy, A.-R. M., Galal, W. F., and Salman, A. M.: Geological appraisal of the Theban cliff overhanging the Hatshepsut temple at Deir el-Bahari, Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean, 30, 275–295, 2022.

Cleveland, R. B.: STL: A seasonal-trend decomposition procedure based on loess, J. Off. Stat., 6, 3–73, 1990.

Colesanti, C. and Wasowski, J.: Investigating landslides with space-borne Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) interferometry, Engineering Geology, 88, 173–199, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2006.09.013, 2006.

Collins, B. D. and Stock, G. M.: Rockfall triggering by cyclic thermal stressing of exfoliation fractures, Nature Geosci., 9, 395–400, https://doi.org/10.1038/ngeo2686, 2016.

Corominas, J., Matas, G., and Ruiz-Carulla, R.: Quantitative analysis of risk from fragmental rockfalls, Landslides, 16, 5–21, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-018-1087-9, 2019.

Ćwiek, A.: Old and Middle Kingdom tradition in the Temple of Hatshepsut at Deir el-Bahari, Études et Travaux (Institut des Cultures Méditerranéennes et Orientales de l'Académie Polonaise des Sciences), 61–93, ISBN 978-8392231981, 2014.

de Falco, A., Resta, C., and Squeglia, N.: Satellite and on-site monitoring of subsidence for heritage preservation: A critical comparison from Piazza del Duomo in Pisa, Italy, in: Geotechnical Engineering for the Preservation of Monuments and Historic Sites III, edited by: Lancellotta, R., Viggiani, C., Flora, A., de Silva, F., and Mele, L., CRC Press, London, 548–559, https://doi.org/10.1201/9781003308867-39, 2022.

de Haas, T., McArdell, B. W., Conway, S. J., McElwaine, J. N., Kleinhans, M. G., Salese, F., and Grindrod, P. M.: Initiation and Flow Conditions of Contemporary Flows in Martian Gullies, Journal of Geophysical Research. Planets, 124, 2246–2271, https://doi.org/10.1029/2018JE005899, 2019.

Dehls, J. F., Bredal, M., Penna, I., Larsen, Y., Aslan, G., Bendle, J., Böhme, M., Hermanns, R., Haugsnes, V. S., and Noel, F.: InSAR Norway: Advancing Geohazard Understanding through Wide-Area Analysis, EGU General Assembly 2024, Vienna, Austria, 14–19 April 2024, EGU24-4400, https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu24-4400, 2024.

De Pedrini, A., Ambrosi, C., and Scapozza, C.: The 1513 Monte Crenone rock avalanche: numerical model and geomorphological analysis, Geogr. Helv., 77, 21–37, https://doi.org/10.5194/gh-77-21-2022, 2022.

Dietrich, A. and Krautblatter, M.: Deciphering controls for debris-flow erosion derived from a LiDAR-recorded extreme event and a calibrated numerical model (Roßbichelbach, Germany), Earth Surface Processes and Landforms, 44, 1346–1361, https://doi.org/10.1002/esp.4578, 2019.

Draebing, D., Mayer, T., Jacobs, B., and McColl, S. T.: Alpine rockwall erosion patterns follow elevation-dependent climate trajectories, Commun. Earth Environ., 3, 1–12, https://doi.org/10.1038/s43247-022-00348-2, 2022.

Draebing, D., Mayer, T., McColl, S., Schlecker, M., and Jacobs, B.: Relief and elevation set limits on mountain size, Research Square [preprint], https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-5156557/v1, 2024.

Dupuis, C., Aubry, M.-P., King, C., Knox, R. W., Berggren, W. A., Youssef, M., Galal, W. F., and Roche, M.: Genesis and geometry of tilted blocks in the Theban Hills, near Luxor (Upper Egypt), Journal of African Earth Sciences, 61, 245–267, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jafrearsci.2011.06.001, 2011.

Engen, S. H., Gjerde, M., Scheiber, T., Seier, G., Elvehøy, H., Abermann, J., Nesje, A., Winkler, S., Haualand, K. F., Rüther, D. C., Maschler, A., Robson, B. A., and Yde, J. C.: Investigation of the 2010 rock avalanche onto the regenerated glacier Brenndalsbreen, Norway, Landslides, 21, 2051–2072, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10346-024-02275-z, 2024.

Erismann, T. H. and Abele, G.: Dynamics of rockslides and rockfalls: With 10 tables, Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 316 pp., ISBN 978-3662046395, 2001.

Ezzy, M., Jacobs, B., Krautblatter, M., Grosse, C. U., Helal, H., and Ismael, M.: Assessment of the rock fall geo-hazards of the sub-vertical rock cliffs behind the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut (MTH), Luxor, Egypt, Engineering Geology, 358, 108429, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enggeo.2025.108429, 2025.

Ferretti, A., Prati, C., and Rocca, F.: Permanent scatterers in SAR interferometry, IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing, 39, 8–20, https://doi.org/10.1109/36.898661, 2001.

Ferretti, A., Fumagalli, A., Novali, F., Prati, C., Rocca, F., and Rucci, A.: A New Algorithm for Processing Interferometric Data-Stacks: SqueeSAR, IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sensing, 49, 3460–3470, https://doi.org/10.1109/TGRS.2011.2124465, 2011.

Frank, F., McArdell, B. W., Oggier, N., Baer, P., Christen, M., and Vieli, A.: Debris-flow modeling at Meretschibach and Bondasca catchments, Switzerland: sensitivity testing of field-data-based entrainment model, Nat. Hazards Earth Syst. Sci., 17, 801–815, https://doi.org/10.5194/nhess-17-801-2017, 2017.

Gado, T. A., El-Hagrsy, R. M., and Rashwan, I. M. H.: Projection of rainfall variability in Egypt by regional climate model simulations, Journal of Water and Climate Change, 13, 2872–2894, https://doi.org/10.2166/wcc.2022.003, 2022.